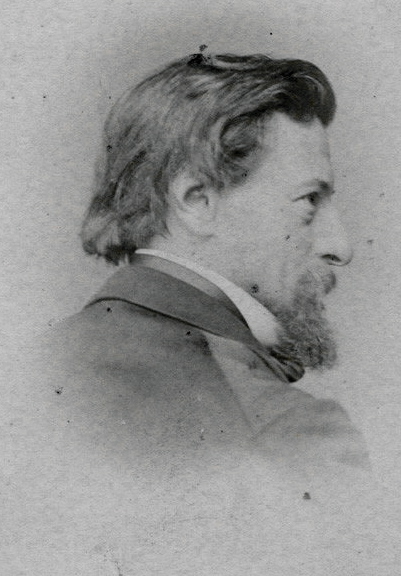

Charles Henry Bennett. Photographers: John and Charles Watkins. c. 1865. Albumen print. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Charles Henry Bennett was a prolific illustrator, graphic satirist, book-cover designer and writer. Employed as a jobbing artist whose economic troubles were typical of his profession in the mid-nineteenth century, his work appeared in a wide variety of periodicals and humorous books for adults and children. Viewed in his own time as a practitioner in the comic tradition of John Leech, George Cruikshank and Richard Doyle, and active for only twelve years, Bennett died as the result of an unspecified illness at the age of thirty-eight. His reputation was nevertheless considerable; as M. H. Spielmann remarks in her 1895 history of Punch, his ‘career was short, though not too short for fame’ (p.76). His books are currently among the rarest and most highly prized of their kind, and although he has never been the subject of a monograph his impact is surprisingly well-charted by his contemporaries, who write at length of his art and especially of his personality. These texts enable us to reconstruct the main outlines of his life and career.

Charles Bennett was born in Tavistock Court, near to the present day Covent Garden, London, on 26 July 1828. His father’s occupation is not recorded in the Census returns, although the family was probably middle class or at least at the lower end of bourgeois respectability. The adjoining streets contained a wide variety of shops and businesses, and the Bennetts may have been shopkeepers or otherwise in trade. The neighbourhood was popular with actors, writers and artists, as well as teachers of dancing and singing, and the atmosphere, we might surmise, was bohemian.

Charles had little formal education and according to Spielmann spent his early years as a shoemaker, though no firm evidence has been advanced to support this claim. He might have been employed by his father, perhaps in a shop or selling a service. We can say that Bennett’s modest circumstances were fairly unusual in the world of art. There were of course a number of others who came from trade or working class backgrounds, most notably E. H. Wehnert, Robert Barnes and A.W Bayes; however, unlike these contemporaries he appears to have been entirely self-trained, and never benefitted from any formal tuition. Mastering the rudiments of draughtsmanship, he acquired the skills of design as he produced his earliest published work. With the exception of a single study in The British Museum there are no surviving drawings to judge his progress as he converted himself into an artist, and his work in print is the only solid evidence on which to judge his art.

Handicapped by the limitations of class, limited education and poor health, his upward movement was arduous. In 1848 following his marriage he settled in the respectable district of St Clement Danes, where the Census return for 1851 records him as an ‘artist-portrait painter’; but there are no surviving paintings and he may have failed to gain any commissions, perhaps as the result of the untrained effect of any work he may have produced. Like so many artists unable to find a niche in a crowded market he turned in the mid-fifties to drawing for the print-industry, and it was only as a ‘designer on wood’, as he is described in the Census of 1861, that he made his mark.

This medium seems to have suited his natural industriousness and small-scale capacity for invention. The Dalziels, the engravers of much of his work, describe him as a perfectionist for whom no effort was too great (p.330), and like one of Samuel Smiles’s artist-heroes in Self Help (1859), he persevered in a difficult profession. His sketches appeared in 1855 in Diogenes, a short-lived rival to Punch, and other illustrations featured in the Illustrated Times,the Comic Times and The Illustrated London News. These early, apprentice pieces were published when he was in his late twenties, although he quickly established himself with a series of popular books for children which were issued from the mid-fifties in the form of Aesop’s Fables and continued into the sixties with The Adventures of the Young Baron Munchausen, The Nine Lives of a Cat and Mr Wind and Madam Rain. His juveniles ran in parallel to the adult work, and he gained wide if uneven recognition in 1860 for his version of The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Bennett’s books demonstrated great versatility, and contemporaries noted his ‘highly original humorous fancy’ (Vizetelly, p. 389) and ‘droll’ invention (Notes & Queries, p.524). His comedic talents found a natural home when he was appointed as a staff-artist at Punch, contributing 230 satiric designs from February 11, 1865 to 23 March 1867. In many ways a successor of Richard Doyle, Bennett’s drolleries range from caricature and anthropomorphic satire to situational comedy. Dream-like and strange, his illustrations fuse pragmatic social observation with a fantastical excess, the realities of the contemporary world as if he were watching adults from a child-like (and thoroughly deranged) perspective. His time at Punch was limited, but he made a significant contribution to its development, infusing a note of sometimes threatening oddness that gave the magazine an added dimension; as Martin Ray remarks, his drawings are characterised by ‘verve and malice’ (p.132).

Whatever the effect of his imagery, Bennett was an easy-going and witty individual. He enjoyed an extensive social life and was one of founding members of the celebrated Savage Club, which was set up for the bohemian element in intellectual circles. Perhaps feckless, rarely solvent, and always willing to indulge others, his company was enjoyed in several of the coteries of the period. He was especially popular among his colleagues at the Punch Table, and several commentaries remark on his engaging character. Shirley Brooks, one of the staff writers, was taken by his gentleness and jovial manner and others dubbed him ‘cheerful Charlie’. Spielmann describes him as one of the magazine’s ‘favourite sons’, whose attendances at the regular dinners made them the ‘merriest of all’, animating the company with his ‘animal spirits and bright, good humour’ (pp.76–78) in the manner of someone who is not quite a gentleman. But the affection Bennett inspired is more accurately gauged by surviving documents in which his colleagues banter about his long hair, the self-conscious display of his status as an unconventional artist; feigning offence, his work-mates presented him with a mock-subscription of a few pennies that enabled him to have it cut (Spielmann, p.77). This is masculine humour of the raconteur’s club, a sort of banter based on rivalry and respect, though even in jest it acknowledges the illustrator’s developing financial problems. More telling still is his friends’ response when the artist died (2 April 1867) at the end of a long illness and before he could complete the customary graffiti signature, which all members cut into the surface of the table. The circumstances are recounted in Graham Everitt’s history of period:

He left a widow and eight children unprovided for, for his health having precluded it, no life insurance had been effected. The Punch men, however, with the unselfishness with so nobly characterizes them, put their shoulders to the wheel for the family of their stricken comrade [and coming up with the idea that they would perform] the well-known farce of ‘Box and Cox’ [performed a testimonial at the Adelphi and again in Manchester by which] a large sum was raised [on-line edition, no page numbers].

This charitable act is a measure of the esteem in which Bennett was held, providing his family with immediate, but short-lived relief. His estate went into administration and his total wealth is recorded in the National Probate as under £200: the same amount as that left by the impoverished Wehnert. His wife subsequently applied for relief to The Royal Literary Fund, receiving in 1868 the sum of £40; The British Library contains a pathetic application in which she attaches a copy of their marriage certificate of 1848 and other documents pleading her case.

Nothing more is known of his widow and children, although the artist’s melancholy end was remembered by colleagues and commentators. Spielmann notes how his life, despite his successes, was ‘hard’, and yet another example of the ‘pinch of poverty’ (p.76–78) which blighted the careers of many professional artists of lowly status who did not have the security of established wealth. In an age when artistic production was commodified within a free market, even a highly industrious practitioner working in a commercial context was hard-pressed to earn enough to live. Though a household name and favourite in the nursery and the club, Bennett was reduced to the level of the wage-slave, and always on The Road to Ruin. He was buried on 8 April, 1867, in Brompton Cemetery. Ernest Griset, an artist of a similar cast of mind, took his place at the table.

Related Material

Works Cited

Baker, Anne Pimlott. ‘Bennett, Charles Henry’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online version.

British Census Returns, 1841–1868. Ancestry.co.uk.

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work, 1840–1890. 1901; new ed. London: Batsford, 1978.

Cooke, Thomas. A Practical and Familiar View of the Science of Physiognomy. London: for Mrs Cooke, 1819.

Corrigan, Grahaeme. ‘Amusing Aesop’. Children’s Literature Archive. www.http//:ryerson.ca/childrenslit/group37.html

de Maré, Eric. The Victorian Woodblock Illustrators. London: Gordon Fraser, 1980.

Doyle, Richard. The Foreign Tour of Messrs. Brown, Jones, and Robinson. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1854–55 .

Everitt, Graham. English Caricaturists and Graphic Humourists of the Nineteenth Century. Reproduced at wikisource.org/wiki/

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; Lund Humphries, 2004.

Grandville, J. J. Vie Privée et Publiques des Animaux. Paris: Hetzel, 1842.

King, Edmund. Victorian Decorated Trade Bindings, 1830 –1880. London: The British Library, 2003.

Lavater, J.C. Essays on Physiognomy. London: Robinson, n.d.

Le Brun, Charles. Heads Representing the Various Passions of the Soul as They are Expressed in the Human Countenance. London: Laurie & Whittle, 1794.

Ray, Gordon. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1976.

‘Review’. Notes and Queries. 2nd Series X (29 December 1860): 524.

‘Review’. The Bookseller. 1 (1872): 16–18.

‘Review’. The Literary Gazette. n.s 71 (5 November 1859): 445–446.

‘The Fables of Aesop’. The Economist 9 June 1858: 35.

Redfield, James. Comparative Physiognomy. New York: For the Author, 1852.

‘The Juvenile Illustrated Books of the Period’. The Art Journal. 5 (1859): 380.

Smiles, Samuel. Self Help. London: Murray, 1859.

Spielmann, M. H. The History of Punch. London: Cassell, 1895.

Vizetelly, Henry. Glances Back Through Seventy Years. London: Kegan Paul. Trench, Trübner & Co., 1893.

Last modified 17 March 2014