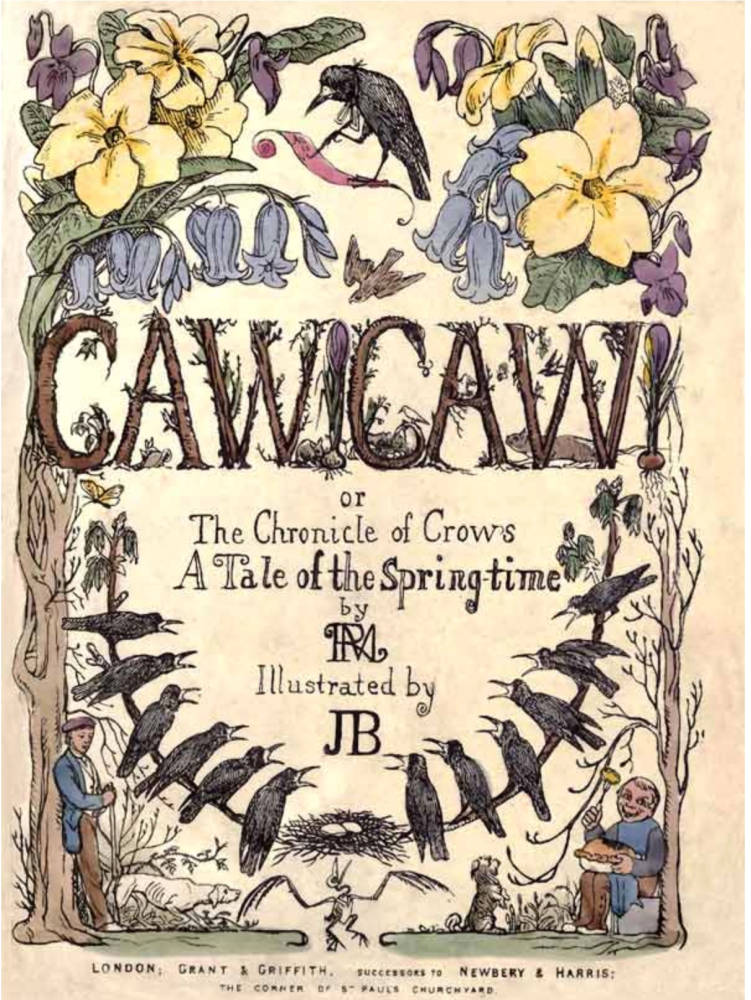

Blackburn’s book illustrations brought her wide acclaim and broadened her audience. Blackburn’s two most famous children’s books, Caw! Caw!, or The Chronicle of Crows, A Tale of the Spring-Time and Pipits, both written by the anonymous R.M., can be accessed today through online archives and historical print editions. Caw! Caw! is a rhyming children’s book about the life cycle of a flock of crows—we move from the joyous nesting and birth of baby crows, to their slaughter by a local farmer and his friends, to the escape of some who return to their nesting place full knowing, as the final couplet reads: “‘Caw! Caw!’ they say, ‘How well we know/ There is no joy unmixed with woe.’” The book, now forgotten, quickly went into a second edition. Not unsurprisingly, an 1855 reviewer for The Morning Herald commented on the illustrations, not the text: “‘The illustrations are excessively droll, and no impartial crow could attempt to dispute the fidelity of the portraiture’” (qtd. Fairley 44).

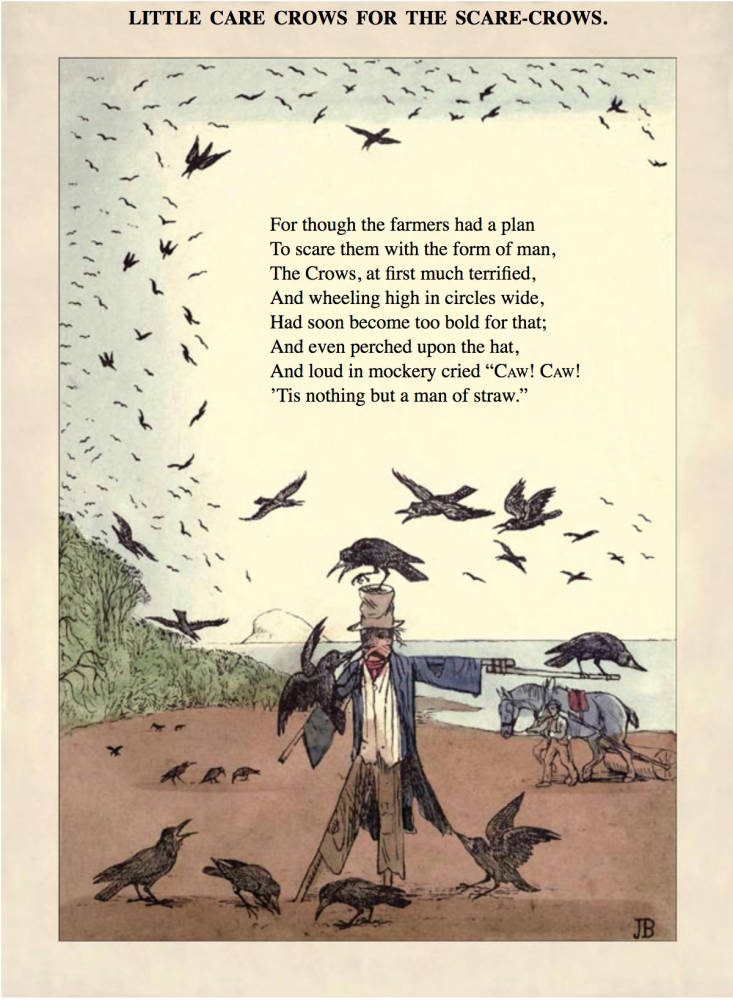

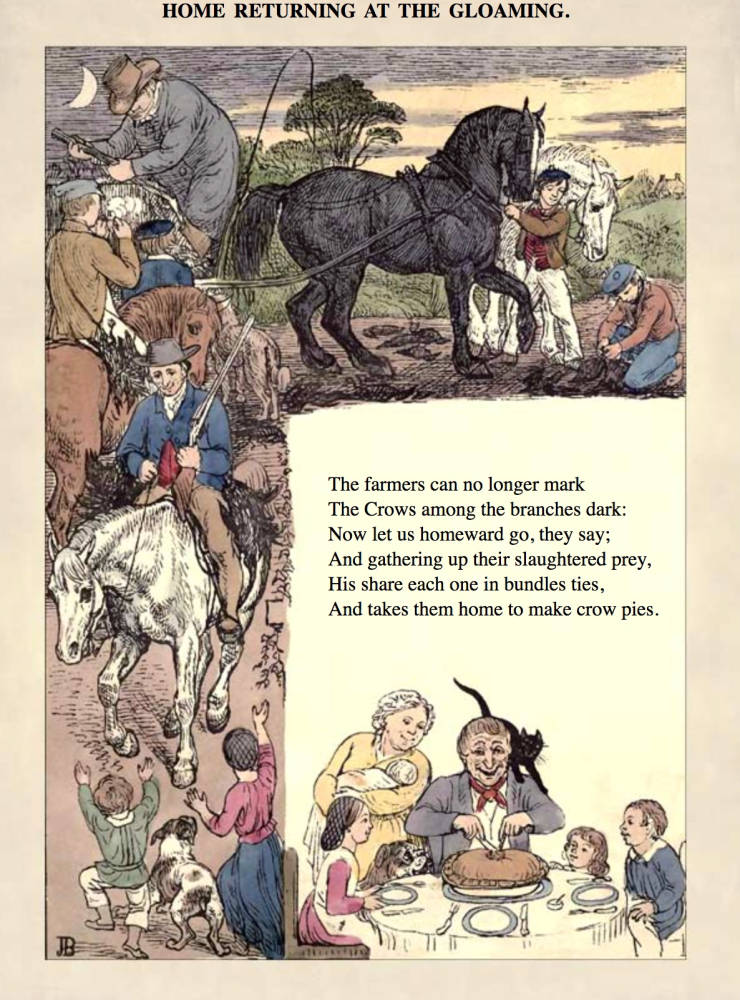

Left The Title-page Caw Caw. Middle: Little Care Crows for the Scare Crow. Right: Home Returning from the Gloaming. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Some of the illustrations are amusing. For example, accompanying the crows’ discovery that the scarecrow “‘Tis nothing but a man of straw,’” Blackburn includes a full-page illustration of authentically rendered crows akin to those she includes in Birds Drawn from Nature; the crows appear to be amusing themselves as they peck at the farmers’ crops and perch on the scarecrow’s coat and hat. But other pictures are far from droll. Blackburn shows the act of shooting the birds and the young crows piteously plummeting to the ground. Chilling is the depiction of the farmer’s family including their pets sitting at table about to devour a crow pie—an illustration which, like the scarecrow picture, anticipates Potter’s Peter Rabbit (1902) illustrations of Peter’s father put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor and the blackbirds pecking at the ineffective scarecrow in Mr. McGregor’s garden. The hand-colored plates in Caw! Caw! show off Blackburn’s skill in drawing birds and animals—the horses, owls, bats, and dogs are lifelike, and the landscape is skillfully drawn and well-integrated with the text.

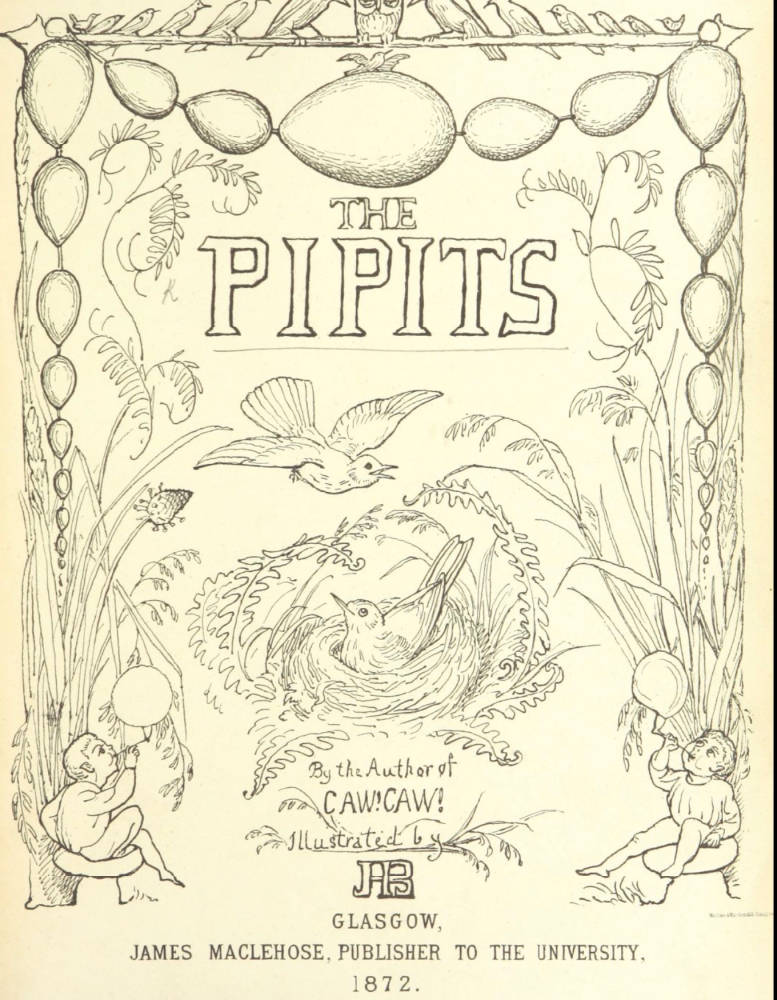

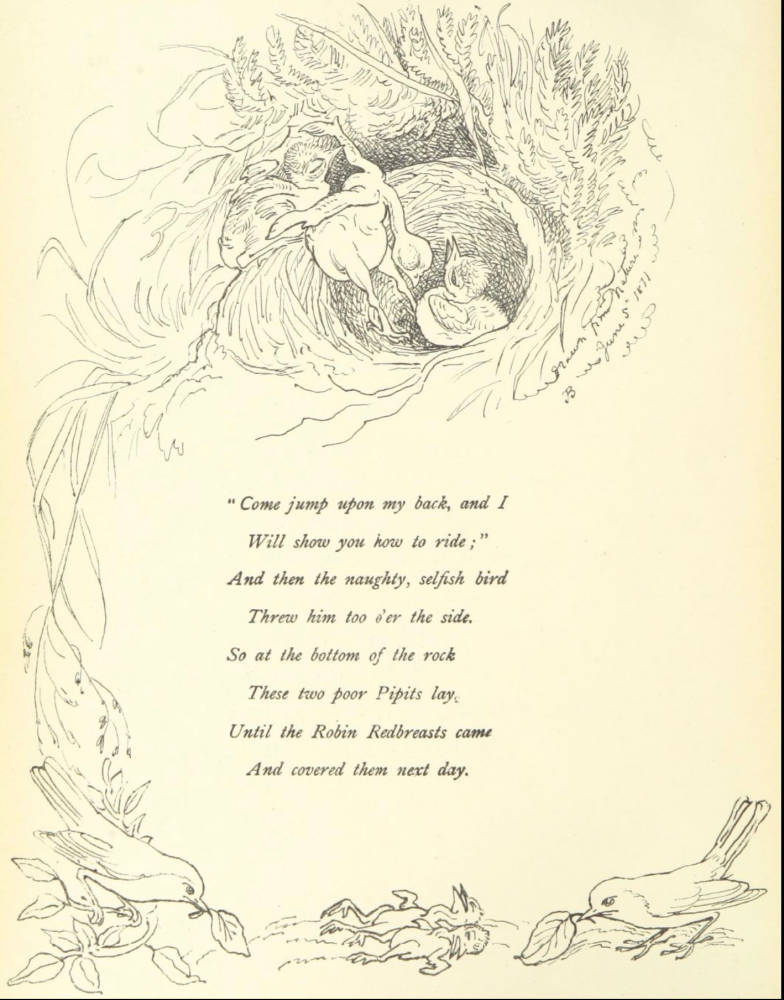

Also told in rhyme, The Pipits illustrations are simple black-and-white lithographs that convey a striking mastery of birds and animals including a dodo, mice, owl, and peacock. Again, these illustrations are clearly from the hand of a skilled naturalist and resemble those in her ornithological books. The narrative is insipid and inferior to its companion Caw! Caw! The story anthropomorphizes the birds in its treatment of Mr. and Mrs. Pipit as a married human couple; Mrs. Pipit, a boasting mother, longs to hatch an enormous egg—which turns out to be an egg of a fledging cuckoo abandoned by its own mother—and she even hosts two parties to show it off.

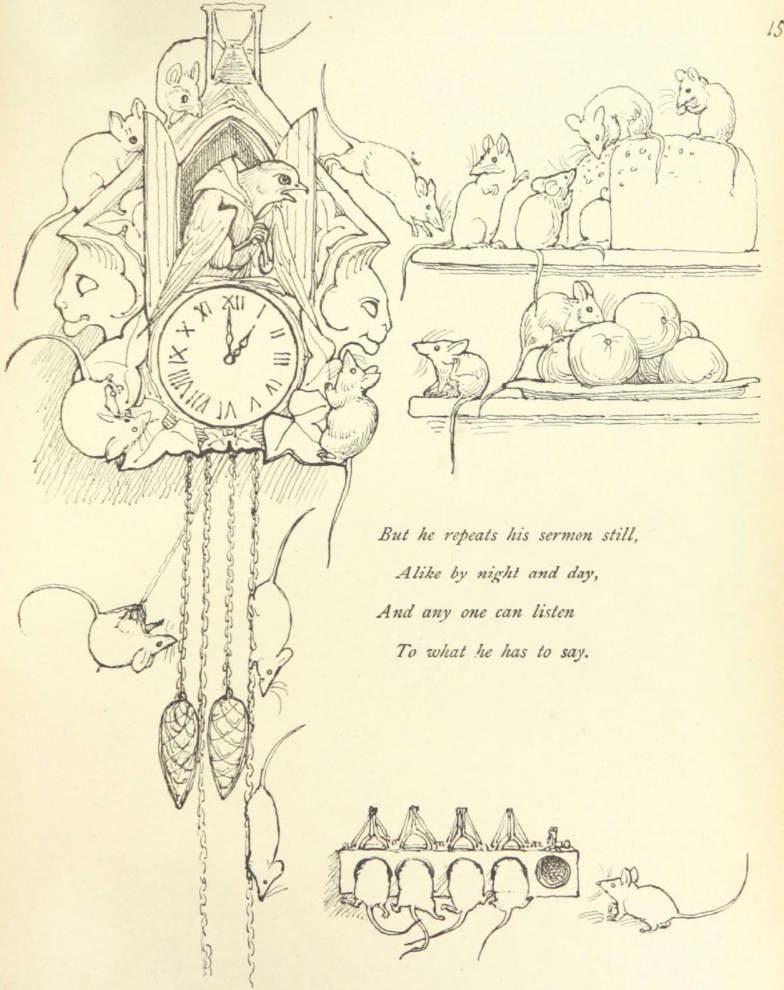

Left: Title-page of the The Pippits. Middle: “Come Jump on my back.” Right: But he repeats his sermons still.

The tale is noteworthy for Blackburn’s astute understanding of the behavior of a cuckoo that Darwin includes in the sixth edition of On the Origin of Species (1882). Blackburn’s sketch shows that the fledgling cuckoo ejected the pipit chicks from the nest of a Meadow Pipit, confirming a 1788 observation of Edward Jenner, an English physician and scientist, that was dismissed in 1836 as impossible by English naturalist Charles Waterston. Thus, Blackburn in substantiating Jenner also proves incorrect Gould’s assertion in The Birds of Great Britain (1873) that it was the host Pipit parent who mistakenly ejected its own young when tidying the nest. Gould corrected his mistake based on a drawing made by Blackburn for Pipits, which was sent to him by the Duke of Argyll. Darwin, in turn, verified the cuckoo’s behavior “from a ‘trustworthy source’ received by Gould” (55)—the source, though unnamed, is Jemima Blackburn.

Regrettably, The Pipits ends moralistically with the reformation of the very cuckoo who kills the pipit chicks by ejecting them from the nest (the cuckoo also inadvertently causes the death of Cock Robin by flirting with Cock Robin’s “wife” Jenny Wren and, in so doing, incites a sparrow who causes the robin’s death). The final drawing accompanying this scene is one that ten-year-old Beatrix Potter copied into one of her sketchbooks. Potter recreates Blackburn’s whimsical drawing of mice climbing on a clock and munching on food in a pantry while the now honest cuckoo sermonizes to all creatures who will listen—at least a few mice seem to be doing so in the sketch. In its frequent reprinting, Potter’s copy of Blackburn’s illustration speaks to the influence of the elder naturalist on the younger. Linda Lear notes in Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature (2007) that Blackburn’s Birds Drawn from Nature (1868) “sharpened [Potter’s] eye for nature as well as art” (32) and in a footnote refers to Dr. Mary Noble’s assertion that Blackburn inspired Potter’s storybook character with the same first name—Jemima Puddle-Duck (459n20).

Kenneth Parkes in a review of Robert Fairley’s 1993 Blackburn’s Birds concludes that “Rob Fairley has done the history of ornithology in general, and of bird painting in particular, a fine service by bringing to our attention the life and work of Jemima Blackburn, who had a distinct influence on her younger but much better known contemporary, Beatrix Potter” (569). It may seem ironic to end a review of a book designed to raise Blackburn’s profile and reputation by calling attention to Potter, Blackburn’s “better known contemporary,” but Parkes’s praise of Potter, nonetheless, directs us to the influential Blackburn. Jemima Blackburn, who was to many Victorians Bewick’s only rival, deserves to be better known today. Praised by leading critics and artists of her age, she is a consummate Victorian ornithological illustrator and artist whose keen observation of bird behavior even found its way into On the Origin of Species.

Related Material

Bibliography

Blackburn, Jemima. Birds Drawn from Nature. Glasgow: James Maclehose, 1868. Internet Archive online version. Web. 11 January 2021.

_____. Birds from Moidart and Elsewhere. Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1895. Hathi Trust online version. Web. 11 January 2021.

_____. Bible Beasts and Birds: A New Edition of Illustrations of Scripture by an Animal Painter. London: Kegan Paul, 1886. Hathi Trust online version. Web. 11 January 2021.

-----. “Memoirs.” In Jemima: The Paintings and Memoirs of a Victorian Lady. Ed. Rob Fairley. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1988.

Gray, Sarah. “Wedderburn, Jemima.” The Dictionary of British Women Artists. Lutterworth Press, 2009. 278-79.

Lear, Linda. Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2008.

Linder, Leslie. The Journal of Beatrix from 1881 to 1897. 1966. London: Frederick Warne, 1979

.Last modified 10 January 2021