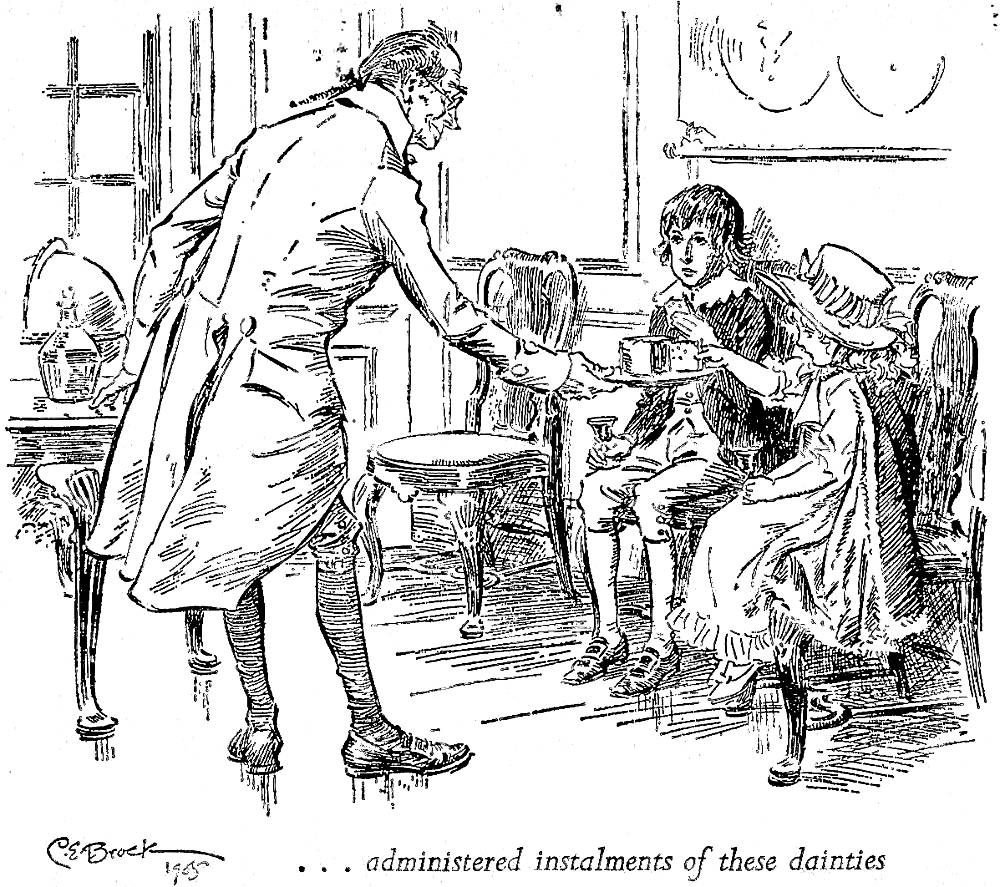

The school-master himself 'administered instalments of these dainties (1905), a half-page line-drawing for Stave Two, "The First of the Three Spirits," 8.8 cm by 10 cm, vignetted (36), is Brock's second flashback to Scrooge's time as a schoolboy, when all his classmates had left for the Christmas holidays, and his younger sister, little Fan, had suddenly appeared to bring her brother home.

Context of the Illustration

"I have come to bring you home, dear brother!" said the child, clapping her tiny hands, and bending down to laugh. "To bring you home, home, home!"

"Home, little Fan?" returned the boy.

"Yes!" said the child, brimful of glee. "Home, for good and all. Home, for ever and ever. Father is so much kinder than he used to be, that home's like Heaven! He spoke so gently to me one dear night when I was going to bed, that I was not afraid to ask him once more if you might come home; and he said Yes, you should; and sent me in a coach to bring you. And you're to be a man!" said the child, opening her eyes, "and are never to come back here; but first, we're to be together all the Christmas long, and have the merriest time in all the world."

"You are quite a woman, little Fan!" exclaimed the boy.

She clapped her hands and laughed, and tried to touch his head; but being too little, laughed again, and stood on tiptoe to embrace him. Then she began to drag him, in her childish eagerness, towards the door; and he, nothing loth to go, accompanied her.

A terrible voice in the hall cried. "Bring down Master Scrooge's box, there!" And in the hall appeared the schoolmaster himself, who glared on Master Scrooge with a ferocious condescension, and threw him into a dreadful state of mind by shaking hands with him. He then conveyed him and his sister into the veriest old well of a shivering best-parlour that ever was seen, where the maps upon the wall, and the celestial and terrestrial globes in the windows, were waxy with cold. Here he produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake, and administered installments of those dainties to the young people: at the same time, sending out a meagre servant to offer a glass of "something" to the postboy, who answered that he thanked the gentleman, but if it was the same tap as he had tasted before, he had rather not. Master Scrooge's trunk being by this time tied on to the top of the chaise, the children bade the schoolmaster good-bye right willingly; and getting into it, drove gaily down the garden-sweep: the quick wheels dashing the hoar-frost and snow from off the dark leaves of the evergreens like spray. [Stave Two, "The First of the Three Spirits," 35-36]

Commentary

Brock through this scene emphasizes that Scrooge's father rejected his son as Scrooge has inexplicably rejected his nephew, Fred. Previous artists after John Leech have generally not had space in their programs to reflect upon Scrooge's emotionally impoverished school days, even though rejection by his father led to the mature businessman's developing an uncharitable, anti-Christmas sentiment. However, several illustrators have included a version of this scene, including Charles Green, whose approach (not published until 1912, although drafted in the 1890s) is far more low-key and far less humorous that Brock's.

In this 1905 illustration, the young Scrooge sits somewhat rigidly as the smiling schoolmaster graciously entertains the student and his sister, little Fan, who, dressed in a gigantic hat and fur-lined cloak, sits on the edge of her chair without her feet touching the floor. Brock's smiling master (not shown in Green's version) in his black 18th c. tail-coat seems to relish playing host to the affluent children, possibly expecting that Master Scrooge has come into an inheritance since he has been suddenly called home. The school-master as Brock depicts him seems to be a genial instructor rather than the sort of hectoring pedagogue who would "glare on Master Scrooge with a ferocious condescension" (35). Although a globe is evident behind the decanter on the table (left) and a map is just discernible on the wall behind the seated children, the "best-parlour" in the school does not look particularly forbidding or spartan. Brock, however, has not given this part of the parlour a carpet, as if to imply frugality or puritan austerity. Delightful as his realisation is, it lacks the satirical edge with which Dickens typically treats schools and school-masters, as in Nicholas Nickleby and David Copperfield.

Although Dickens's original illustrator, Leech, did not develop a realisation of this significant moment from Scrooge's childhood, the early modern artist Arthur Rackham has provided a similar illustration to complement the passage that, in a Freudian sense at least, points the reader towards capitalist Scrooge's back-story, that is, his father's rejection (which modern film adaptations imply that he suffered as a result of his mother's having died in childbirth). However, Rackham's illustration mines the comic potential that Brock has begun to exploit in the scene. As is consistent, however, with the text, Green in The Child Scrooge and His Sister (see below) generates pathos for Scrooge as a boy. Brock demonstrates that Scrooge's sole sibling, gleeful little Fan, is smaller and younger than her brother as her feet do not quite touch the floor as the head-master entertains the pair in his "shivering best-parlour" (35) with the "curiously light" (watered-down) wine and "a block" of stale cake.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1912 and 1915 editions

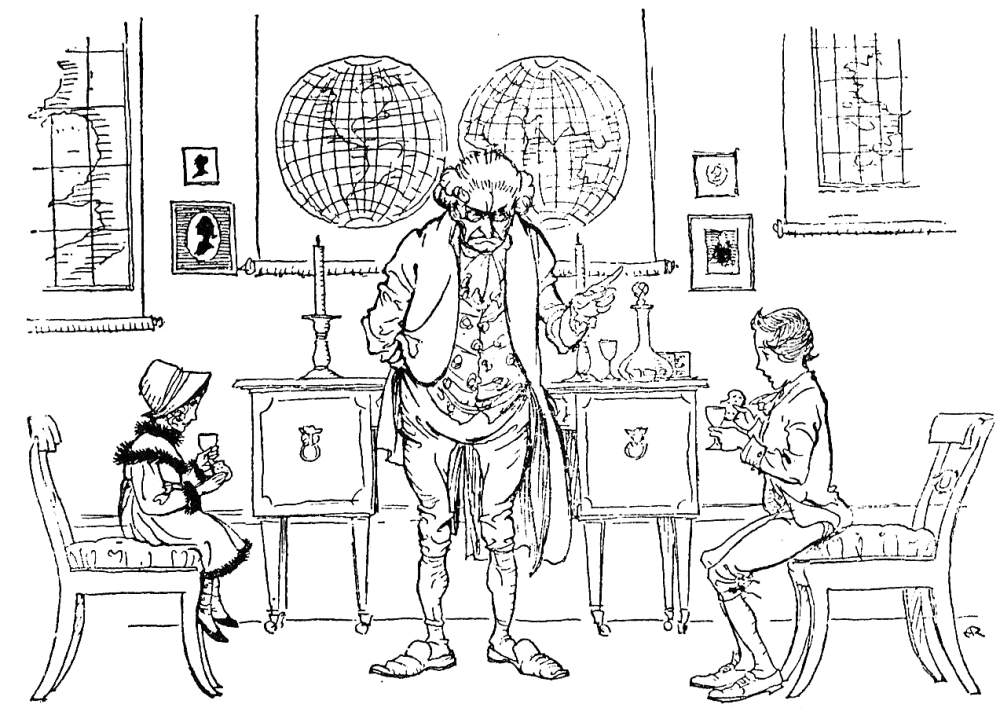

Left: Green's interpretation of Scrooge and his sister's being entertained in the master's study, in He produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake (1912). Right: Rackham depicts the same scene and, like Brock, includes the master himself in He produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake, in the 1915 single-volume, child-oriented edition.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. X.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Created 21 September 2015

Last modified 5 June 2020