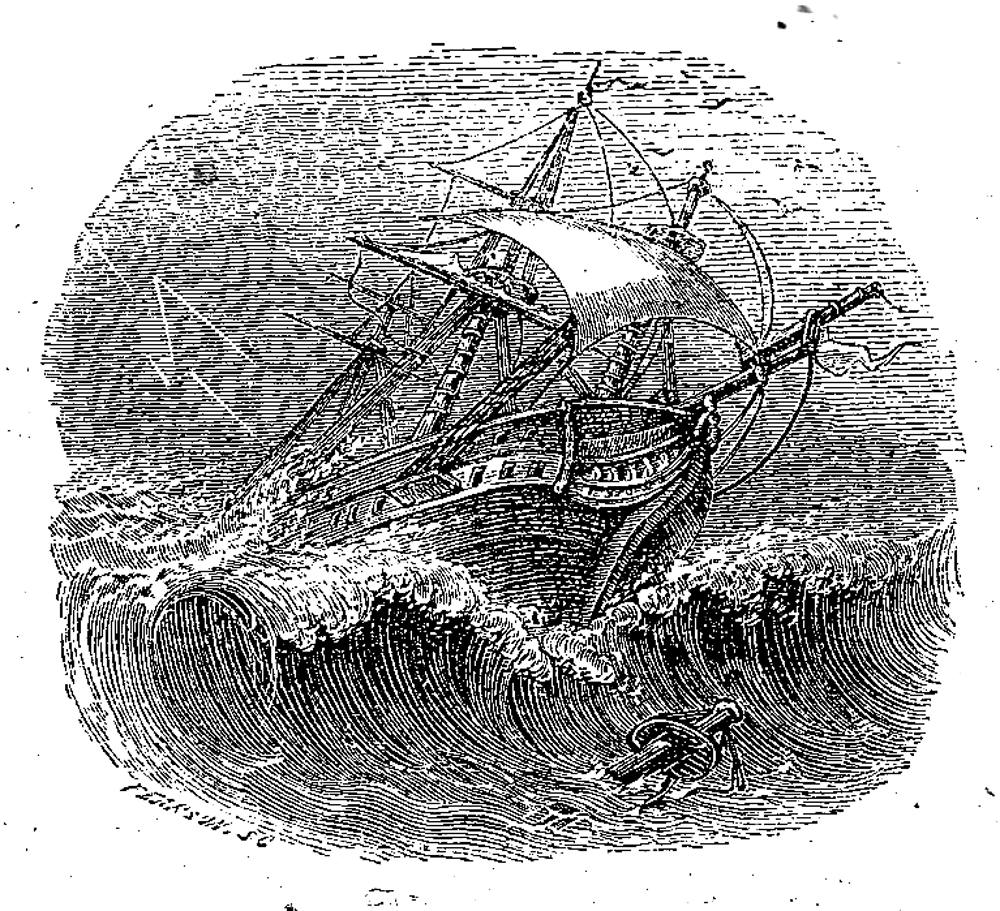

Ship in stormy Seas uncaptioned tailpiece (page xiv) — the volume's final woodblock engraving, a mere vignette, in Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Part II, The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, "Introduction." Quarter-page, vignetted. 5.4 cm high x 6 cm wide. Running head: "Introduction" (xiv).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Final Paragraph

To conclude: having stayed near four months in Hamburgh, I came from thence by land to the Hague, where I embarked in the packet, and arrived in London the 10th of January 1705, having been absent from England ten years and nine months. And here, resolving to harass myself no more, I am preparing for a longer journey than all these, having lived seventy-two years a life of infinite variety, and learned sufficiently to know the value of retirement, and the blessing of ending our days in peace. [Chapter XVI, "Arrived Safe in England," page 394]

Accompanying Poem: William Cowper on the castaway Alexander Selkirk (1782)

I am monarch of all I survey; My right there is none to dispute; From the centre all round to the sea I am lord of the fowl and the brute O Solitude! where are the charms That sages have seen in thy face? Better dwell in the midst of alarms, Than reign in this horrible place.

I am out of humanity's reach; I must finish my journey alone; Never hear the sweet music of speech — I start at the sound of my own; The beasts that roam over the plain My form with indifference see — They are so unacquainted with man, Their tameness is shocking to me.

Society, Friendship, and Love Divinely bestow'd upon man, Oh had I the wings of a dove How soon would I taste you again! My sorrows I then might assuage In the ways of religion and truth, Might learn from the wisdom of age, And be cheer'd by the sallies of youth.

Ye winds that have made me your sport, Convey to this desolate shore Some cordial endearing report Of a land I shall visit no more. [xiii/xiv] My friends, do they now and then send A wish or a thought after me? O tell me I yet have a friend, Though a friend I am never to see.

How fleet is a glance of the mind! Compared with the speed of its flight, The tempest itself lags behind, And the swift-wingèd arrows of light. When I think of my own native land, In a moment I seem to be there; But, alas! recollection at hand Soon hurries me back to despair.

But the sea-fowl is gone to her nest, The beast is laid down in his lair; Even here is a season of rest, And I to my cabin repair. There's mercy in every place; And mercy—encouraging thought! — Gives even affliction a grace, And reconciles man to his lot.

— "Verses, supposed to be written by Alexander Selkirk, during his solitary Abode in the Island of Juan Fernandez," 1782.

Robinson Crusoe as a Model of Self-Help

Samuel Smiles' Self-Help (1859) was at least as influential upon publication as that other landmark publication of 1859, Charles Darwin's Origin of Species:

Whatever may have been the origin of the tale, however virulent may have been the attacks made against its author, as he himself says, by political enemies and senseless critics, the judgment of the most enlightened men of all nations has placed "Robinson Crusoe" upon a height which no sounds of animosity can now reach. What pleasure has this wonderful tale given, and still gives, to all readers! Young and old, rich and poor, find in its pages an unfailing source of pure delight.

It blends instruction with amusement in a way no other production of human intellect has ever succeeded in doing. While depicting a solitary individual struggling against misfortune, it indicates the justice and the mercy of Providence; and while inculcating the duty of self-help, asserts the complete dependence of man upon a higher power for all he stands in need of. ["Introduction," xii]

Among the book's most devoted admirers in the previous century, Dr. Samuel Johnson and Jean Jacques Rousseau, both felt that the book should be read by every boy "first and longest," and Johnson placed it as a modern classic in a short list with Don Quixote and Pilgrim's Progress. The ship that appears in the tailpiece after the dramatic monologue of Alexander Selkirk is not the Hamburg vessel transporting Crusoe to Western Europe, but the original slave-ship, foundering in the waves of Crusoe's island where he will prove himself highly adaptative and resilient — the very incarnation of the doctrine of Self-help.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

References

Cowper, William. "The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk." English Poetry II: From Collins to Fitzgerald. The Harvard Classics. 1909–14. Accessed 17 April 2018. http://www.bartleby.com/41/317.html

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 17 April 2018