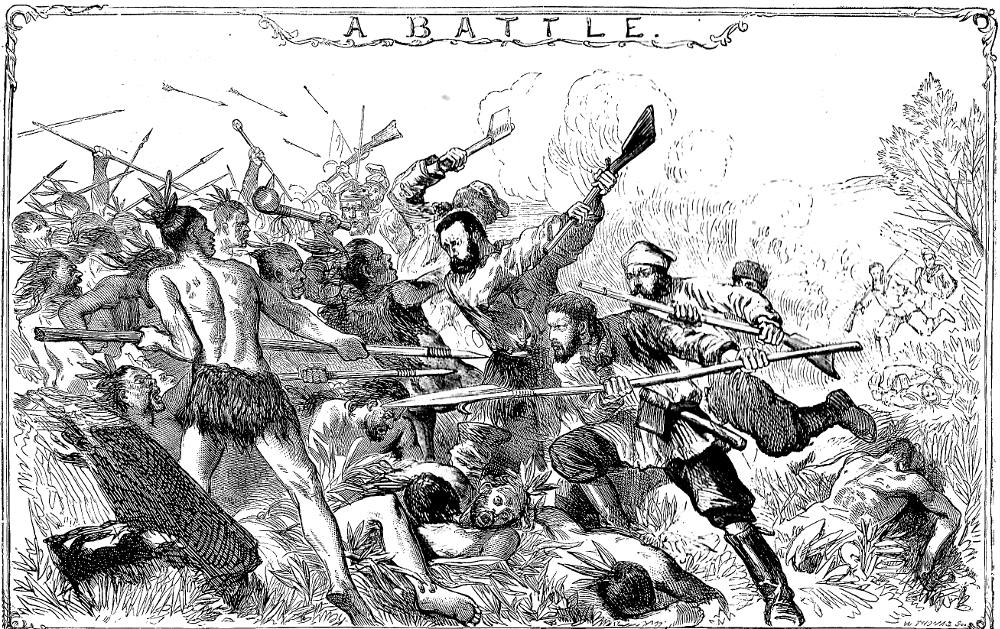

A Battle (page 261) — the volume's sixty-eighth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Part II, The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Chapter III, "The Fight with the Cannibals." Full-page, framed: 13.8 cm high x 21.9 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

When the savages came on, they ran straggling about every way in heaps, out of all manner of order, and Will Atkins let about fifty of them pass by him; then seeing the rest come in a very thick throng, he orders three of his men to fire, having loaded their muskets with six or seven bullets apiece, about as big as large pistol-bullets. How many they killed or wounded they knew not, but the consternation and surprise was inexpressible among the savages; they were frightened to the last degree to hear such a dreadful noise, and see their men killed, and others hurt, but see nobody that did it; when, in the middle of their fright, Will Atkins and his other three let fly again among the thickest of them; and in less than a minute the first three, being loaded again, gave them a third volley.

Had Will Atkins and his men retired immediately, as soon as they had fired, as they were ordered to do, or had the rest of the body been at hand to have poured in their shot continually, the savages had been effectually routed; for the terror that was among them came principally from this, that they were killed by the gods with thunder and lightning, and could see nobody that hurt them. But Will Atkins, staying to load again, discovered the cheat: some of the savages who were at a distance spying them, came upon them behind; and though Atkins and his men fired at them also, two or three times, and killed above twenty, retiring as fast as they could, yet they wounded Atkins himself, and killed one of his fellow-Englishmen with their arrows, as they did afterwards one Spaniard, and one of the Indian slaves who came with the women. This slave was a most gallant fellow, and fought most desperately, killing five of them with his own hand, having no weapon but one of the armed staves and a hatchet.

Our men being thus hard laid at, Atkins wounded, and two other men killed, retreated to a rising ground in the wood; and the Spaniards, after firing three volleys upon them, retreated also; for their number was so great, and they were so desperate, that though above fifty of them were killed, and more than as many wounded, yet they came on in the teeth of our men, fearless of danger, and shot their arrows like a cloud; and it was observed that their wounded men, who were not quite disabled, were made outrageous by their wounds, and fought like madmen. [Chapter V, "A Great Victory," pp. 260-61]

Commentary: Valiant in the face of difficult odds

Although a somewhat rebellious member of the European colony with a definite streak of oppositional defiance, Will Atkins is the ideal military leader in a desperate situation. As the leader of the mutiny, he demonstrated the kinds of logistical and administrative skills required of a successful military commander. The battle scene as the Cassell's house-artist depicts it involves considerable hand-to-hand action — hardly the ideal situation for the badly outnumbered colonists since they cannot use their firearms to a maximal advantage in such close quarters. In consequence, in complete contrast to Cruikshank's earlier illustration of this battle, in the Cassell illustration of the battle some Europeans are using their muskets as clubs, and Atkins (if, indeed, the man in the foreground is the leader) has appropriated a native spear as his weapon of choice in the melee.

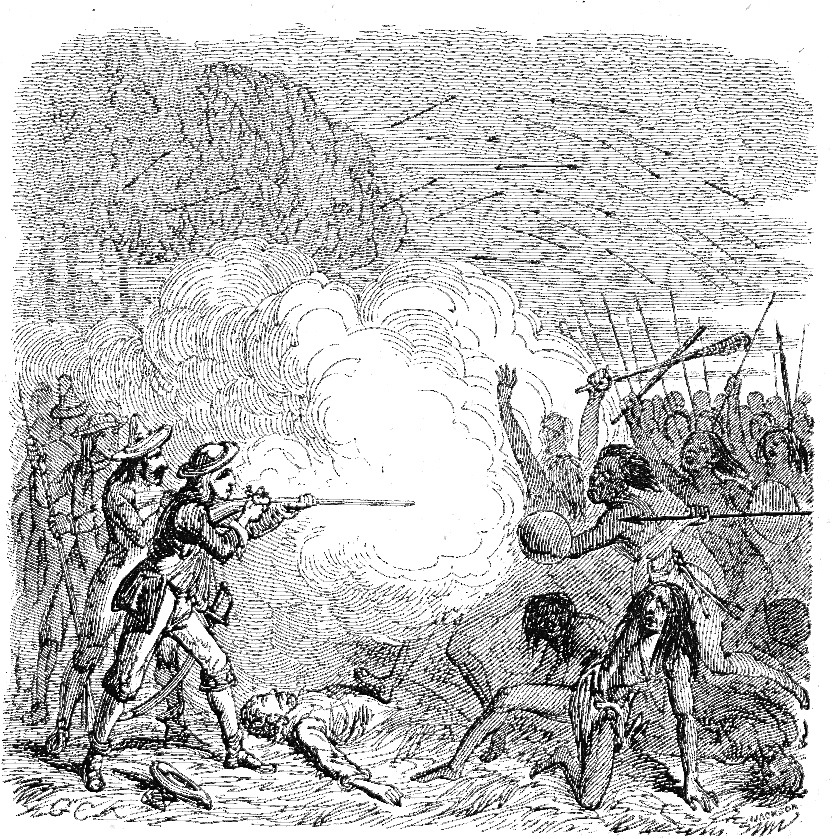

As the arrows fly from the aboriginal to the European side, left to right in the upper register, above the action, the English and Spanish settlers (probably already having discharged their weapons to good effect, if one may judge by the numbers of slain warriors at the bottom of the frame) confront superior numbers of Caribs armed with warclubs and spears. Whereas in the earlier Cruikshank illustration great clouds of gunpowder smoke in the centre of the composition suggest that the Europeans have the advantage, in this 1864 illustration both sides seem evenly matched and the European victory is in doubt. In contrast, in Cruikshank's illustration, on the right hand margin chaos and consternation grip the attackers, who wave their clubs at their adversaries in frustration about the great losses they are sustaining. Whereas Cruikshank presents the "savages" in disarray, the English and Spanish in the 1864 woodblock engraving are not in a disciplined line. But the Europeans are being joined by a few of their fellows (right), and they confront the enemy with resolution born of a determination to save their homes and families.

The natives, whom Cruikshank described as distortions of humanity, are here perfectly credible and quite normal-looking adversaries for the half-dozen Europeans, and the outcome of the battle seems to hang in the balance as neither side is ready to yield the field. The Cassell's artist, then, sees Atkins' adversaries as "noble" savages and proficient warriors, rather than primitive beings dismayed by the god-like weaponry initially wielded by the Europeans, but now no more useful than warclubs and spears. We may account for the difference between the Cruikshank and Cassell's illustrations by the fact that the earlier artist was realising the opening of the conflict whereas the Cassell's artist is illustrating the latter part.

In Part One, Crusoe originally had no intention of interfering in the cannibals' second grisly feast as long as they would leave him alone. However, when Crusoe realizes that one of the victims is bearded, he concludes that he must intervene to preserve the life of a "Christian." However, such intervention may expose him to considerable danger, both in the actual battle to liberate the Spanish captive, in which he and Friday are badly outnumbered, and afterwards, should any of the cannibals escape to return later to take revenge on Crusoe. That same pattern of instability of Crusoe's situation in Part One repeats itself in Part Two when one of the captured natives escapes from the plantation of the two "honest" Englishmen and reports to his fellows on the mainland that a small contingent of Europeans has colonized the island. The result, once again, is an invasion, followed by the Europeans' defeating the aboriginals through their use of superior technology.

Related Material

- The Reality of Shipwreck

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Illustration by Cruikshank (1831)

Above: George Cruikshank's vignette of the same incident, in which the field of battle is much obscured by the smoke of the muskets, Will Atkins leads his men against attacking aborigines (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 29 March 2018