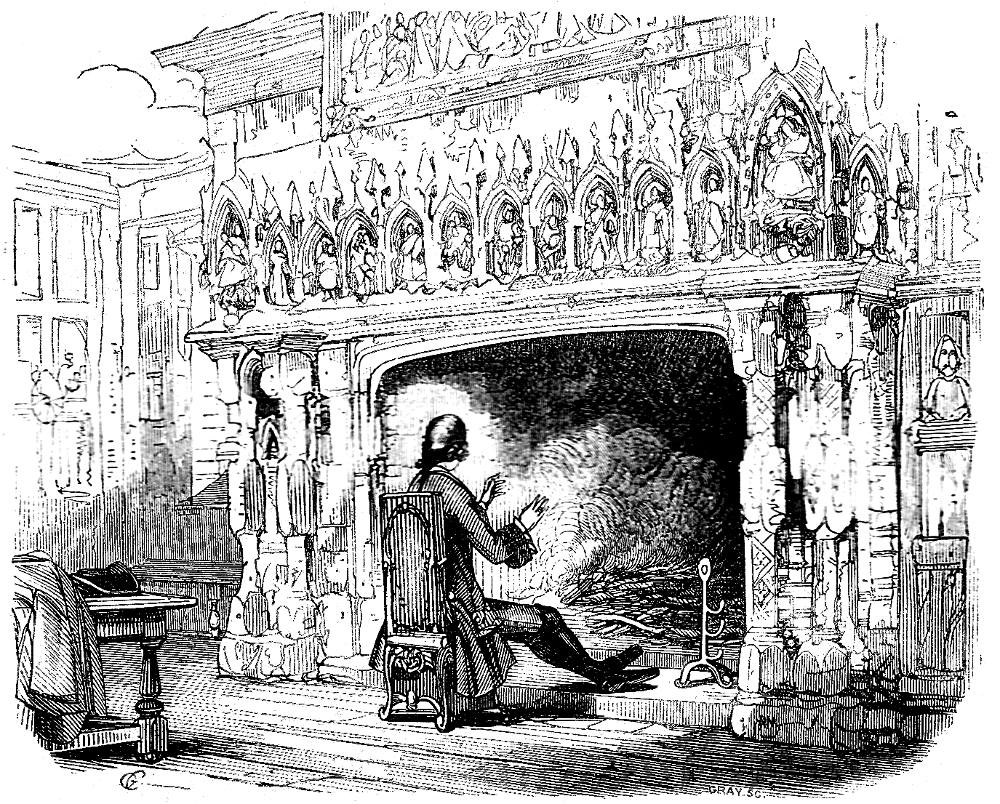

The Best Apartment at The Maypole by George Cattermole. 3 ½ x 4 ½ inches (9.2 cm by 11.2 cm). Vignetted wood-engraving. Chapter 10, Barnaby Rudge. 20 March 1841 in serial publication (eleventh plate in the series). Part 6 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. 2 (part 49), 291. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Context of the Illustration: The Magnificent Setting Dwarfs the Character

Having, in the absence of any more words, put this sudden climax to what he had faintly intended should be a long explanation of the whole life and character of his man, the oracular John Willet led the gentleman up his wide dismantled staircase into the Maypole’s best apartment.

It was spacious enough in all conscience, occupying the whole depth of the house, and having at either end a great bay window, as large as many modern rooms; in which some few panes of stained glass, emblazoned with fragments of armorial bearings, though cracked, and patched, and shattered, yet remained; attesting, by their presence, that the former owner had made the very light subservient to his state, and pressed the sun itself into his list of flatterers; bidding it, when it shone into his chamber, reflect the badges of his ancient family, and take new hues and colours from their pride.

But those were old days, and now every little ray came and went as it would; telling the plain, bare, searching truth. Although the best room of the inn, it had the melancholy aspect of grandeur in decay, and was much too vast for comfort. Rich rustling hangings, waving on the walls; and, better far, the rustling of youth and beauty’s dress; the light of women’s eyes, outshining the tapers and their own rich jewels; the sound of gentle tongues, and music, and the tread of maiden feet, had once been there, and filled it with delight. But they were gone, and with them all its gladness. It was no longer a home; children were never born and bred there; the fireside had become mercenary — a something to be bought and sold — a very courtezan: let who would die, or sit beside, or leave it, it was still the same — it missed nobody, cared for nobody, had equal warmth and smiles for all. God help the man whose heart ever changes with the world, as an old mansion when it becomes an inn! [Chapter the Tenth, 291-92]

However, the since the scene involves Mr. Chester's seating himself before the immense fireplace, in this headpiece for the tenth chapter he would seem to be anticipating the following passage at the end of the twelfth, ten pages later:

"And now, Willet," said Mr. Chester, "if the room’s well aired, I’ll try the merits of that famous bed."

"The room, sir," returned John, taking up a candle, and nudging Barnaby and Hugh to accompany them, in case the gentleman should unexpectedly drop down faint or dead from some internal wound, "the room’s as warm as any toast in a tankard. Barnaby, take you that other candle, and go on before. Hugh! Follow up, sir, with the easy-chair."

In this order — and still, in his earnest inspection, holding his candle very close to the guest; now making him feel extremely warm about the legs, now threatening to set his wig on fire, and constantly begging his pardon with great awkwardness and embarrassment — John led the party to the best bedroom, which was nearly as large as the chamber from which they had come, and held, drawn out near the fire for warmth, a great old spectral bedstead, hung with faded brocade, and ornamented, at the top of each carved post, with a plume of feathers that had once been white, but with dust and age had now grown hearse-like and funereal.

"Good night, my friends," said Mr. Chester with a sweet smile, seating himself, when he had surveyed the room from end to end, in the easy-chair which his attendants wheeled before the fire. "Good night! Barnaby, my good fellow, you say some prayers before you go to bed, I hope?" [Chapter the Twelfth, 303-4]

Commentary

Although Dickens's emphasis is on cheery dialogue of the affable Mr. Chester, Cattermole entirely disregards the other characters, and focuses on the magnificent sixteenth-century fireplace, in front of which the guest seats himself and warms his hands, although only smoke is apparent. Thus, the illustrator relies upon the dialogue and the narratorial remarks to describe the character of Edward Chester's effete, aristocratic father. Cattermole perhaps suggests an element of discomfort in the narrowness of the chair in which Mr. Chester, faced turned towards the fireplace and away from the viewer, has seated himself. Dickens left the actual description of the traveller to Phiz, in Mr. Chester Takes his Ease at his Inn (10 April 1841).

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators — A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s ten Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image and text by George P. Landow, with additional commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 65-6.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 14 December 2020