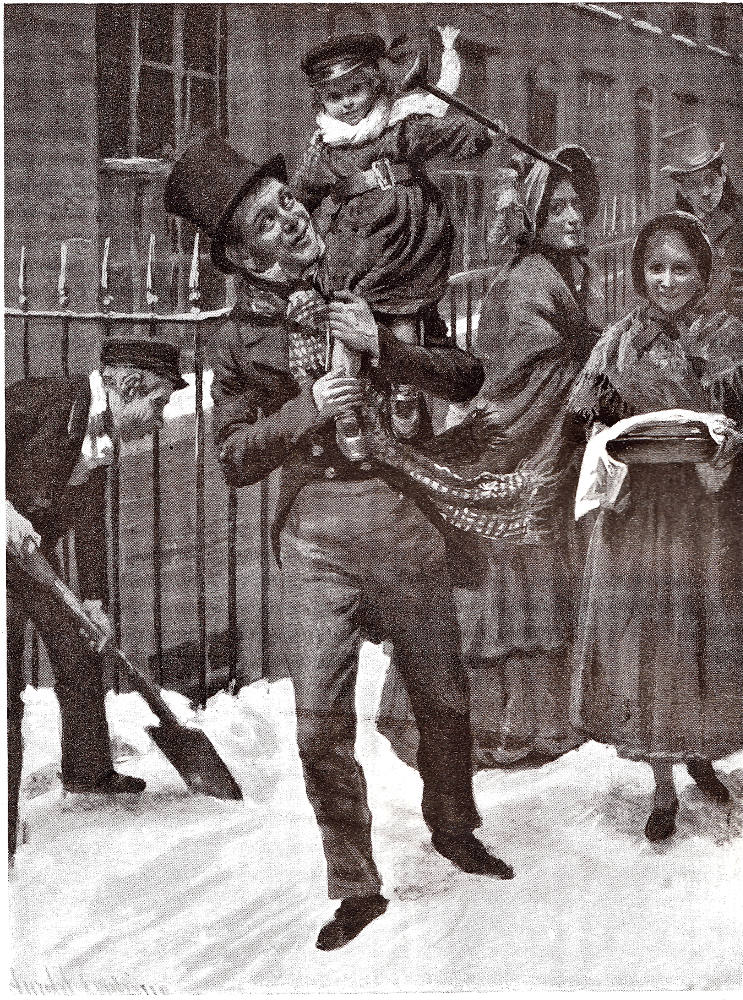

Tiny Tim and His Father; otherwise, "He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant." — originally, Harold Copping's frontispiece for the 1911 edition of A Christmas Carol and subsequently facing p. 52 in the 1924 edition of Character Sketches from Dickens. Colour and black-and-white lithography. 6 by 4 ½ inches (15.2 x 11.3 cm), framed. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated from "Tiny Tim" (1924)

The name of this clerk was Bob Cratchit. He had a wife and five other children beside Tim, who was a weak and delicate little cripple, and for this reason was dearly loved by his father , and the rest of the family; not but what he was a dear little boy too, gentle and patient and loving, with a sweet face of his own, which no one could help looking at.

Whenever he could spare the time, it was Mr. Cratchit's delight to carry his little boy out on his shoulder to see the shops and the people; and to-day he had taken him to church for the first time. [Children's Stories from Dickens, 50]

Commentary: The Evolution of the 1843 Novella's Chief Sentimental Moment

The snowy Yuletide scene in which Harold Copping illustrates Bob Cratchit's carrying Tiny Tim home from church through the streets of Camden Town may strike the modern Londoner as somewhat improbable, given the long odds against White Christmases at present. As Paul Simons and Will Pavia have ably argued in the London Times for 24 December 2008, that Londoners should be depicted as "scraping the snow from pavements in front of their dwellings" in A Christmas Carol is not so improbable if we assume that the Christmas season depicted in that best-seller of 1843 is not the one previous, but rather one of the series from 1817 through 1822, when Dickens was a child of five through ten years of age, and the south of England experienced six White Christmases in swift succession, together with daytime highs of -2 to -6 Celsius. The newspaper columnists attribute this "little Ice Age" to "a series of colossal volcanic eruptions that enveloped the globe in dust and shrouded the sun" (4). This was the same period in which the Shelleys visited Switzerland, enduring one of Europe's coldest summers on record, a min-climate-change that generated the tale that would become Frankenstein (published in 1818). Thus, one may reasonably interpret Dickens's depiction of the Cratchits' Christmas not merely as a paean to the seasonal, middle-class family gathering, but as an invocation of his childhood Christmases with his family before his father fell into debt and was sent to the Marshalsea Debtors' Prison.

In order to permit warmer hues to dominate the scene and sharply contrast the crisp snow underfoot, Copping gives Tiny Tim a velvet snowsuit of intense scarlet, set against red-brown brick row-houses and backed by passengers in red-brown clothing. Complementing the scene Dickens so fleetingly mentions in Stave 3, "The Second of the Three Spirits," or "Christmas Present," Copping offers us a seasonal, lower-middle-class street scene with area railings in the backdrop that is probably quite out of character with the Hungry Forties during which Dickens actually composed the all of the Christmas Books (1843-48). Smiling Bob is respectably clad, with little hint in the picture that his Sunday best is " thread-bare." Copping's Tiny Tim is certainly diminutive — even to the point of having a head out of normal proportions for a child of his age. But the chief objection a New Historicist might raise is the illustration's fundamentally sweet vision of the suburban London streets of the period, especially the clean, well-dressed, cheerful pedestrians who smile benignly as father and son pass. These cheerful Londoners seem a far cry from the necessitous, shabby denizens of the metropolis who would have seen Bob return home from church with his physically challenged son on his shoulder. Although Copping gives us the tiny crutch, he merely suggests the boy's iron leg-brace which the letterpress unequivocal describes as supporting his limbs.

Harold Copping has created a scene which Dickens does not actually give us, but which Mary Angela Dickens briefly sketches in Children's Stories from Dickens. In the 1843 novella, for Scrooge and the Spirit in passing through the busy London streets had earlier seen "poor revelers," "innumerable people, carrying their dinners to the bakers' shops." These "dinner-carriers" Copping has blended with Dickens's later image of Bob and Tim arriving at their own door. Penguin's editor of the two-volume Christmas Books (1971), Michael Slater, cites the unpublished notes of eminent Dickensian T. W. Hill about Christmas baking: "On Sundays and on Christmas Day, when bakers were legally forbidden to bake bread, people would take their joints of meat, etc., to the bake-houses to cook" (260). Such a young woman, perhaps as much smiling already at the prospect of a piping hot joint as enjoying the sight of the happy father and son, is depicted standing immediately to Bob's left.

Other Editions' Versions of the Kindly Clerk and his Handicapped Child (1867-1912)

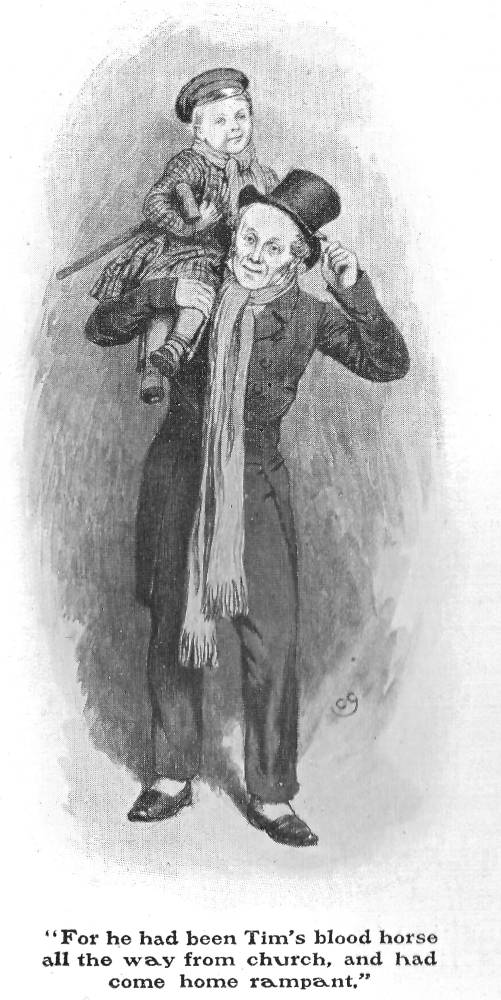

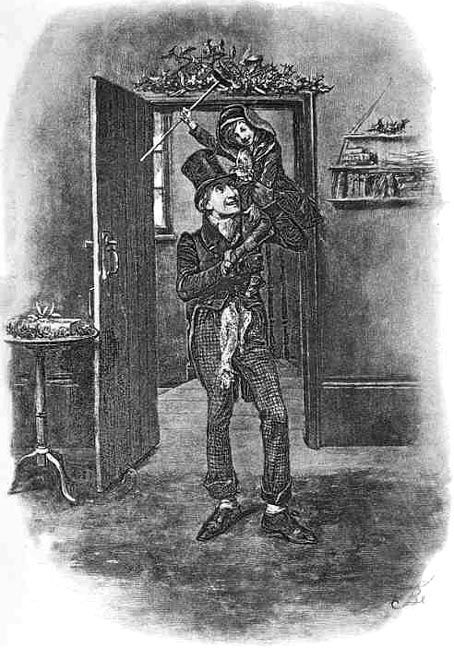

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr., makes the wintery scene the subject of his headpiece for the third stave in the 1869 single-volume edition: Tiny Tim's Ride. Right: Charles Greene's Pears' Centenary Edition illustration for The Christmas Books (1912): Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim: For he had been Tim's blood horse all the way home from church, and had come home rampant.

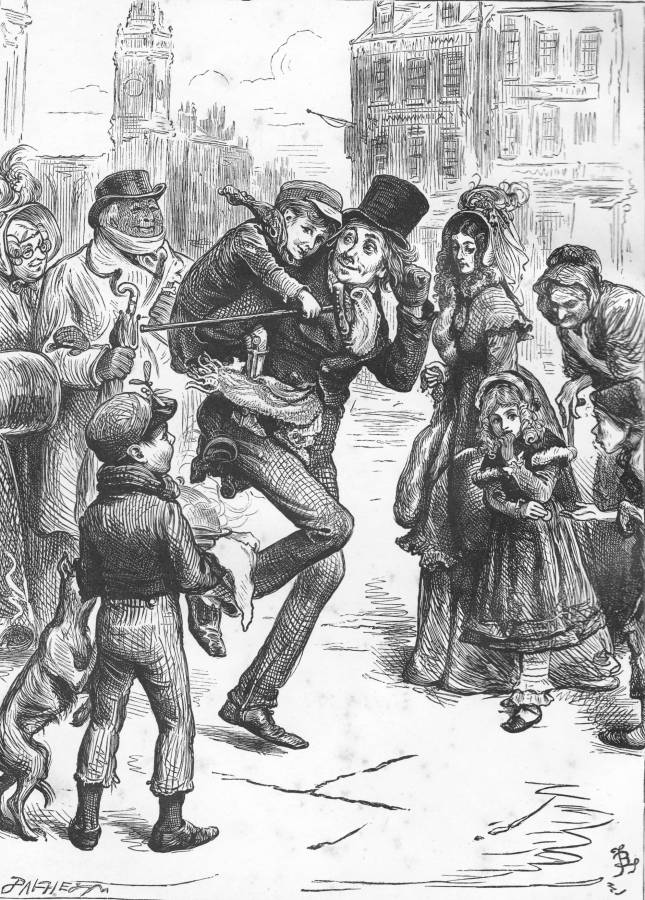

Left: Fred Barnard's 1878 woodblock engraving of Bob Cratchit carrying Tim through the streets of London, He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, and come home rampant", in the British Household Edition. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s version of the kindly father and his crippled child in the Diamond Edition: Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim (1867). Right: Fred Barnard's photogravure frontispiece for his Character Sketches from Dickens (1885): Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim arriving home.

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story for Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Harold Copping. London, Paris, New, York: Raphael Tuck, 1911.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela [Charles Dickens' grand-daughter]. Dickens' Dream Children. London, Paris, New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Hearne, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1989.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini; illustrated by Harold Copping. Character Sketches from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924. Copy in the Paterson Library, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to A Christmas Carol." The Christmas Books. 2 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971. Rpt. 1978. Vol. 1, pp. 257-261.

Simons, Paul, and Will Pavia. "Dreaming of a white Christmas? Put it down to Dickens's nostalgia for his lost childhood." The Times. 24 December 2008. Page 4.

Created 1 March 2006 Last updated 16 October 2023