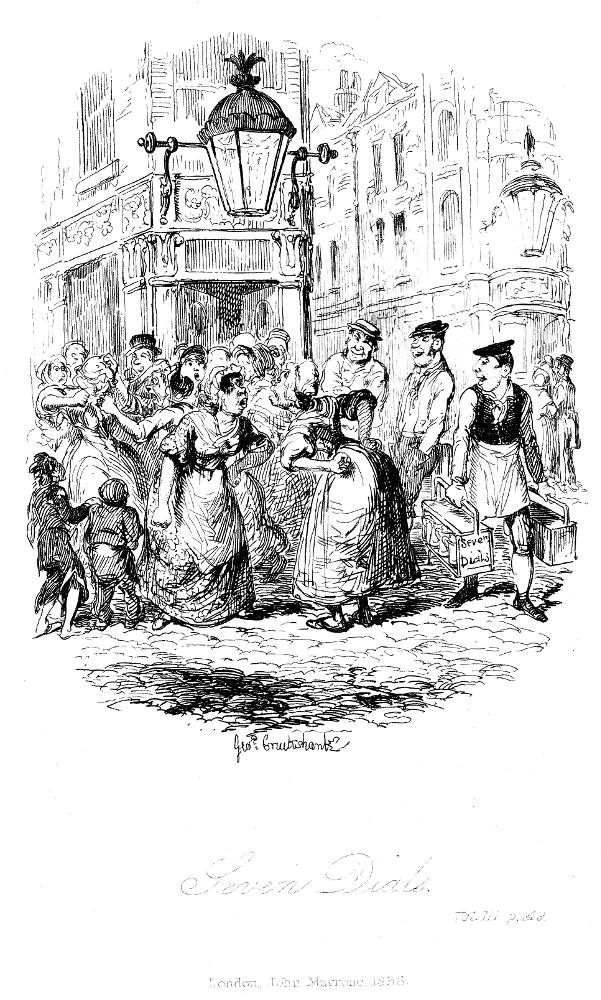

The Seven Dials (full-page illustration) by George Cruikshank. Copper-plate engraving (1836) and steel-engraving (1839). Original dimensions: 10 cm high x 7.7 cm wide (4 by 3 inches); dimensions of the revised engraving 11.7 x 9.4 (4 ⅝ by 3 ¾ inches), vignetted, facing page 51. Cruikshank's original illustration for the 1836 Second Series of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, fifth chapter, duodecimo, faces the half-page engraved title-page vignette. First published by John Macrone, St. James's Square, London. The chief difference between the 1836 and 1839 engravings again lies in the darkness of the background, but Cruikshank also seems to have made the spectators more sharply defined in the copper-plate engraving. In the original Second Series volume, Cruikshank uses the vigorous altercation in the notorious thoroughfare as a keynote. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: The Harridans Take It to the Street

The stranger who finds himself in "The Dials" for the first time, and stands Belzoni-like, at the entrance of seven obscure passages, uncertain which to take, will see enough around him to keep his curiosity and attention awake for no inconsiderable time. From the irregular square into which he has plunged, the streets and courts dart in all directions, until they are lost in the unwholesome vapour which hangs over the house-tops, and renders the dirty perspective uncertain and confined; and lounging at every corner, as if they came there to take a few gasps of such fresh air as has found its way so far, but is too much exhausted already, to be enabled to force itself into the narrow alleys around, are groups of people, whose appearance and dwellings would fill any mind but a regular Londoner's with astonishment.

On one side, a little crowd has collected round a couple of ladies, who having imbibed the contents of various "three-outs" of gin and bitters in the course of the morning, have at length differed on some point of domestic arrangement, and are on the eve of settling the quarrel satisfactorily, by an appeal to blows, greatly to the interest of other ladies who live in the same house, and tenements adjoining, and who are all partisans on one side or other.

"Vy don't you pitch into her, Sarah?"exclaims one half-dressed matron, by way of encouragement. "Vy don't you? if my 'usband had treated her with a drain last night, unbeknown to me, I'd tear her precious eyes out— a wixen!"

"What's the matter, ma'am?" inquires another old woman, who has just bustled up to the spot.

"Matter!" replies the first speaker, talking at the obnoxious combatant, "matter! Here's poor dear Mrs. Sulliwin, as has five blessed children of her own, can't go out a charing for one arternoon, but what hussies must be a comin', and 'ticing avay her oun'usband, as she's been married to twelve year come next Easter Monday, for I see the certificate ven I vas a drinkin' a cup o' tea vith her, only the werry last blessed Ven'sday as ever was sent. I'appen'd to say promiscuously, 'Mrs. Sulliwin,' says I——,'"

"What do you mean by hussies?"interrupts a champion of the other party, who has evinced a strong inclination throughout to get up a branch fight on her own account ("Hoo-roa,"ejaculates a pot-boy in parenthesis,"put the kye-bosh on her, Mary!"),"What do you mean by hussies?"reiterates the champion.

"Niver mind,"replies the opposition expressively, "niver mind; yougo home, and, ven you're quite sober, mend your stockings."

This somewhat personal allusion, not only to the lady's habits of intemperance, but also to the state of her wardrobe, rouses her utmost ire, and she accordingly complies with the urgent request of the bystanders to"pitch in,"with considerable alacrity. The scuffle became general, and terminates, in minor play-bill phraseology, with"arrival of the policemen, interior of the station-house, and impressive dénouement." ["Scenes," Chapter 5, "Seven Dials," pp. 51-52 in the 1839 edition; pp. 147-150]

Seven Dials, the British equivalent of Paris's St. Antoine

. . . where misery clings to misery for a little warmth, and want and disease lie down side-by-side, and groan together. — John Keats on Seven Dials.

Fred Barnard and George Cruikshank have taken very different approaches to the notorious warren known as "The Seven Dials," a breeding ground of vice, disease, and crime at the junction of seven roads in Covent Garden. Originally laid out by Thomas Neale, Member of Parliament and real estate developer, in the early 1690s, He intended the Seven Dials to be a fashionable address, in much the same manner as Place Vaugeois (originally, Place Henri IV) in Paris, but the housing development deteriorated quickly into an Anglo-Irish slum. The only revenant of Neale's original intention is the neoclassical Sundial Pillar erected in 1693-4, designed by architect Edward Pierce as the centrepiece for the conjunction of the streets, with six sundial faces, the seventh 'style' being the column itself. In the early nineteenth century, the availability of cheap lodgings caused an influx of poor Irish labourers, who patronised a legion of gin-shops in the vicinity, an area celebrated in a comic song by Moncrieff. Whereas even poor wine is expensive for the working poor in the Defarges' Wine Shop in Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, rendering the suburb of St. Antoine a breeding ground for vice and revolution, the cheap gin of London seems to act as a soporific, encouraging petty crime but nullifying the possibility of the concerted action necessary for a revolution.

'Tom King and the Frenchman" [to which Dickens alludes at the opening of the sketch] was annotated first by A. L. Hayward in 1924, who writes: Tom King was a character in W. T. Moncrieff's farce Monsieur Tonson. He described himself as "a jolly dog" who worried to distraction M. Morbleu, a French barber of Seven Dials, by repeated enquiries for a Mr. Thompson. The Irish had settled here from Elizabethan times. And by the beginning of the nineteenth century, St. Giles became the dirtiest slum of London with a lot of the Irish living in filth and poverty, and it was often called 'little Dublin'. By the time Dickens wrote Sketches by Boz, Seven Dials was no longer a place for pardonable merry-making of old England, but a noisy, riotous place where the Irish either idled about the gin-shops, or scolded, drank, squabbled, fought and swore on the street. — Takao Sajjo.

Michael Slater notes that this "comic reportage" (53) of is one Dickens's earliest Tibb's-narrated accounts of life on the London streets, from Bell's Life in London for 27 September 1835 as "Scenes and Characters No. 1." The "all-female brawl" has not yet fully broken out, but the verbal sparring (centre) is a humorous prologue to a scene that might result in something more disturbing — and, indeed, the adherents on either side have already begun to pull each other's hair (left) as four men look casually upon the scene, regarding the altercation as essentially funny, while the two children (lower left) are genuinely concerned that their mother is not faring well. In contrast to the crude, bellicose posturing of "Mary" and "Sarah" in the irregular square resulting from the conjunction of two alleyways are the twin gas-lamps and the ornate cornice with a lyre motif, producing a harmonious neoclassical architectural setting for the rowdy "hussies." "Belzoni-like" (that is, like the Egyptian explorer and professional raconteur Giovanni Battista Belzoni , 1778-1823) we are positioned by Cruikshank so as to view the entire fray objectively, seeing both adversaries and their adherents equally, but perhaps siding with the commentator carrying two loads of pots. Even though the name "Belzoni" conjures up an exotic setting far away on the desert sands (the explorer of Egyptian antiquities was the first to penetrate into the second pyramid of Giza), the picture opposite prepares the reader for a confrontation in a section of the metropolis utterly foreign to Dickens's middle-class readers, so that the picture does not merely prepare the reader for the brawl; it also undercuts the classical allusion of "The Gordian knot" (51), the historical allusion to "the maze at Hampton Court" and the topical allusion of "the maze at the Beulah Spa" which opened in August 1831, its neoclassical gardens having been laid out by Decimus Burton, the noted architect, who also designed the Spa House and The Lodge. The erudite allusions appealing to the well-informed and well-educated reader who is about to penetrate the mysteries of the Dials contribute to the narrator's sophisticated tone and verbal posturing, which the brawling Irish women sharply undercut simultaneously (the text on page 51, right, and the contrasting Cruikshank image, left). The two alleyway entrances on either side of the open door (centre rear) imply a certain theatricality or staged quality to the scene, as if the reader is watching the action unfold on stage, in a "real-life" drama whose principals are neither aristocrats nor bourgeoisie; although representative of the lowest elements of London society, Dickens and Cruikshank render them worthy of our attention.

The History of Seven Dials

SEVEN DIALS. An open area in the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, on what was once "Cock and Pye Fields", from which seven streets, Great Earl-street, Little Earl-street, Great White-Lion-street, Little White-Lion-street, Great St. Andrew's street, Little St. Andrew's-street, Queen street, radiate, and so called because there was formerly a column in the centre, on the summit of which were seven sun-dials, with a dial facing each of the streets. [Cunningham, 445]

In the Middle Ages, the land on which Seven Dials is situated belonged to the Hospital of St. Giles, a leper hospital, which was taken over by Henry VIII in 1537. The Crown subsequently let the hospital land on a series of leases. In 1690, William III granted Thomas Neale, freehold of the land known as 'Marshland' or 'Cock and Pye Fields' (named after a public house on the site) in return for his raising large sums of money for the Crown. This was a substantial financial commitment for Neale and he had to find a way to lay out a development that would maximise profit. His solution was imaginative; by adopting a star shaped plan with six radiating streets (subsequently seven were laid out), he dramatically increased the number of houses that could be built on the site. Plans submitted in 1692 to Sir Christopher Wren, the Surveyor-General, for a building licence showed at least 311 houses and an estate church.

Thomas Neale's submission to Sir Christopher Wren, Surveyor General. Courtesy of Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre.

His solution was imaginative, financially ingenious and still stands today in the unique street layout of Seven Dials. By adopting a star-shaped plan with six radiating streets (subsequently seven were laid out) he dramatically increased the number of houses that could be built on the site. Plans submitted in 1692 to Sir Christopher Wren, the Surveyor General, for a building licence, show at least 311 houses and an estate church. At the time rents were charged by the length of the frontage. Neale’s clever layout generated more rental income than that yielded by the squares which were then the fashion.

Construction began in 1693. As soon as the streets had been laid out, sewers installed and the initial corners developed, Neale chose Edward Pierce, the greatest carver of his generation, to build a sundial pillar at the centre of the development, giving Seven Dials its name.

The first inhabitants were respectable gentlemen, lawyers and prosperous tradesmen. However, in 1695 Neale disposed of his interest in the site and the rest of the development was carried out by individual builders over the next 15 years. The area became increasingly commercialised as the houses were subdivided and converted into shops, lodgings and factories.

The Woodyard Brewery was started in 1740 and during the next 100 years spread over most of the southern part Seven Dials. Elsewhere there were the architectural ironmongers, Comyn Ching, woodcarvers, straw hat manufacturers, pork butchers, watch repairers, wigmakers and booksellers as well as several public houses. In the 1790s there was considerable re-facing or reconstruction as leases were renewed. The façades of many of the older houses are now of that date as are several of the painted timber shop fronts. The area was particularly favoured by printers of ballads, political tracts and pamphlets who occupied many of the buildings in and around Monmouth Street. [Seven Dials Trust]

Relevant Illustrations of "The Dials" from the Other Editions, 1867 and 1876

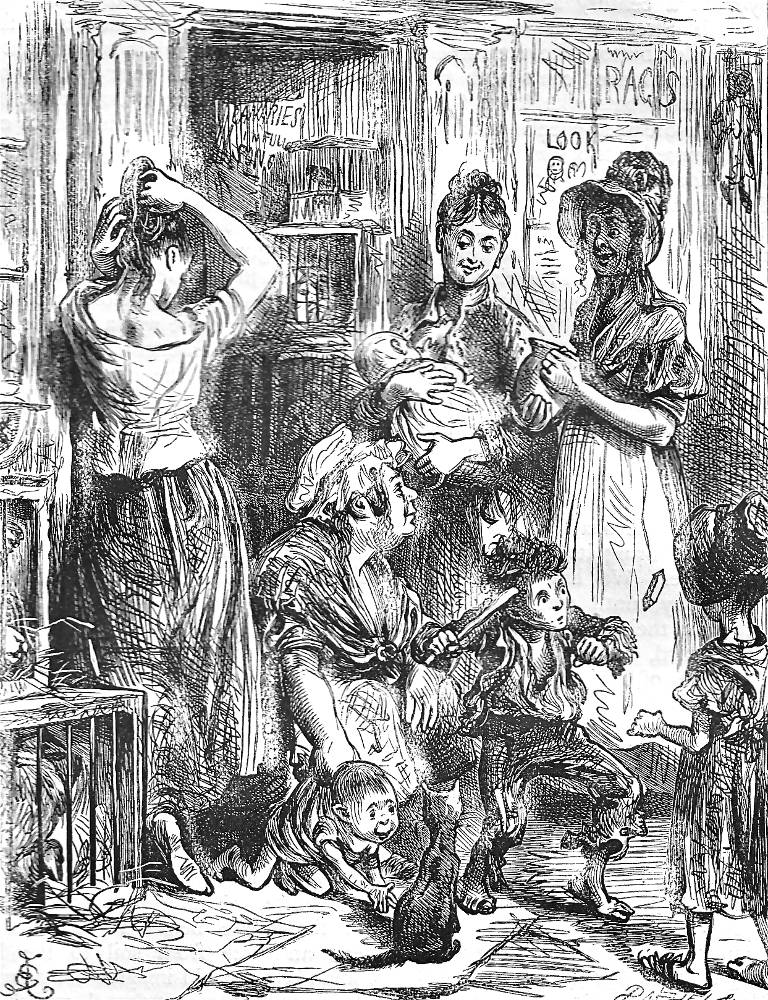

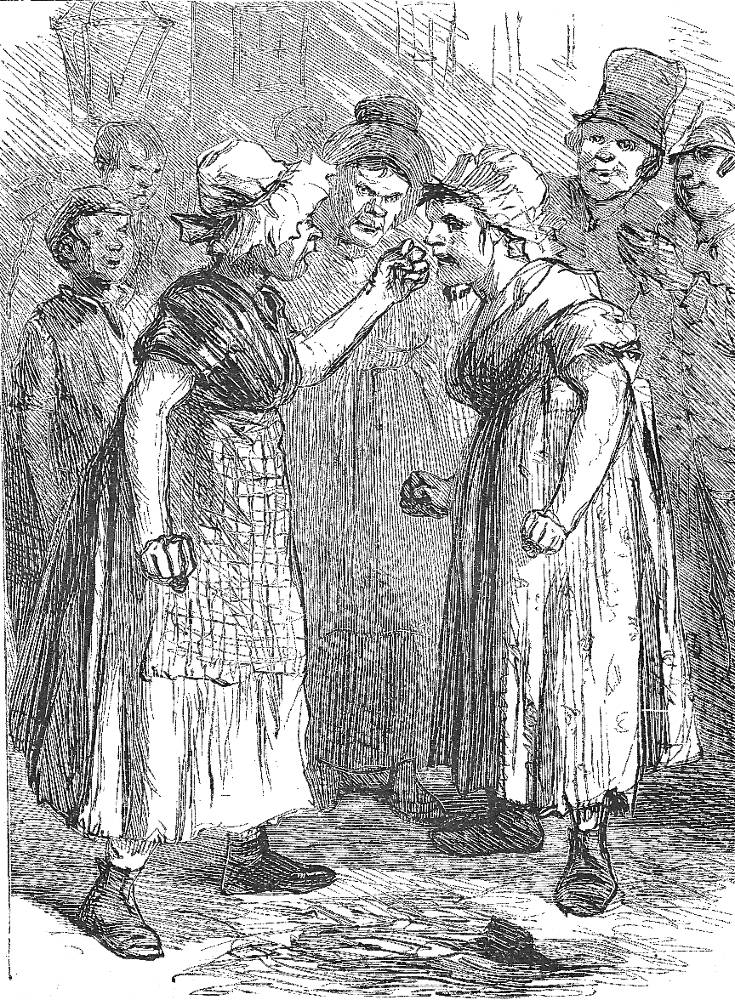

Left: Fred Barnard's much more congenial scene of the female denizens of the Dials passengers conversing amicably in the street, Now, anybody who passed through the Dials on a hot summer's evening, and saw the different women of the house gossiping on the steps, would be apt to think that all was harmony among them, and that a more primitive set of people than the native Diallers could not be imagined (1876). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s version of the altercation between the two Irish women, likely based on the 1839 Cruikshank illustration, Seven Dials. (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Dudley Street, Seven Dials by French social realist Gustave Doré — a busy street scene with sets of shops which can be seen on the right. The shops are selling shoes which are lining up on the floor around the opening from under the ground. Children and their mothers are in front of them. This image was first published in Jerrold's London: a Pilgrimage (1872), on p. 158. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Cruikshank brilliantly realises the comedy of the rich working-class dialogue, capturing in the expressions and postures of the Irish women their feisty characters. Although his pot-boy does not pause as he exhorts "Mary" to pitch into her adversary he is "drawn from life," with a portable rack for his beer tankards. However, the group study by Barnard offers a contrasting view of class and female solidarity akin to Barnard's depiction of the women of St. Antoine in his 1874 illustration of the denizens of the working-class suburb near the Bastille, St. Antoine in which, as here, Barnard sees the women as a civilising force, even in the midst of poverty and privation.

Scanned image, image correction, formatting, and caption by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cunningham, Peter. "Seven Dials." Hand-Book of London. London: J. Murray, 1850. Pp. 445.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "The Seven Dials." Sketches by Boz. Second series. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: John Macrone, 1836. Pp. 143-156.

Dickens, Charles. "Seven Dials," Chapter 5 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 51-54.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 5, "Seven Dials." Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 267-269.

Dickens, Charles. "Seven Dials," Chapter 5 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Vol. XIII. Pp. 32-34.

Dickens, Charles. "Seven Dials," Chapter 5 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 65-69.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Jackson, Lee. "On the Geography of Seven Dials." Dictionary of Victorian London. Punch, Jan.-June, 1842, quoted in Dirty Old London. New Haven: Yale UP, 2014. Web. Accessed 23 April 2017.

Jerrold, William Blanchard. London: A Pilgrimage. Illustrated by Gustav Doré. London: Grant & Co., 1872.

The Seven Dials Trust. "Seven Dials — Its History." Web. Accessed 17 May 2023.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Created 24 April 2017 Last updated 17 May 2023