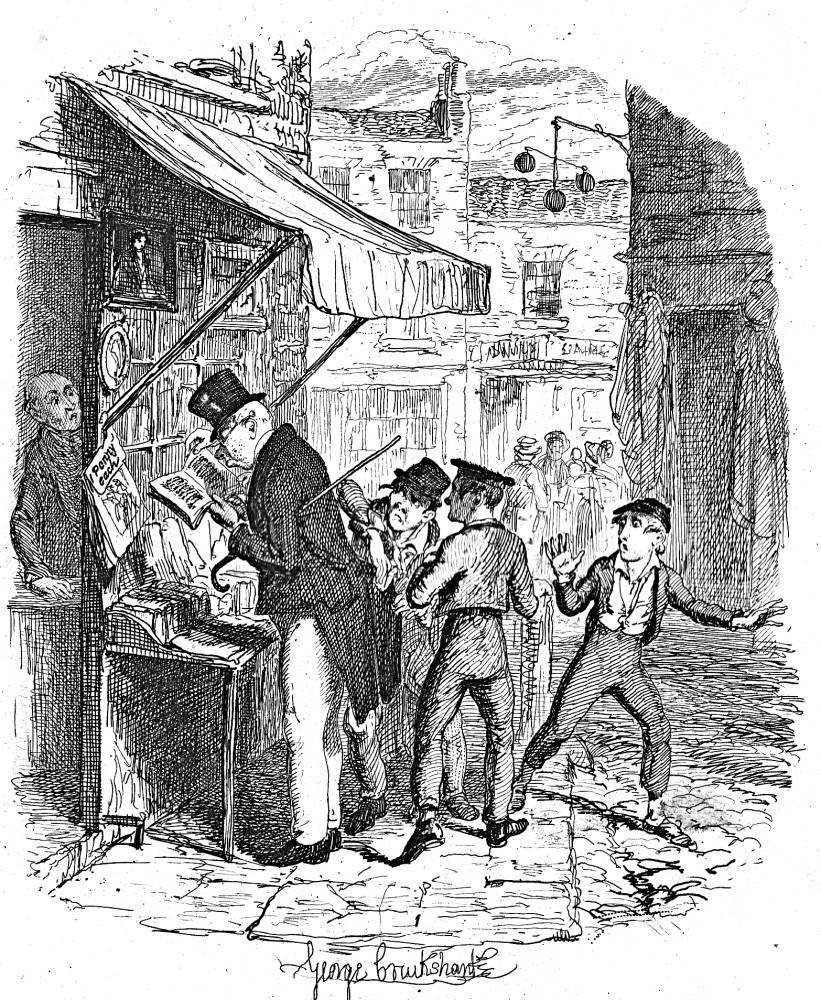

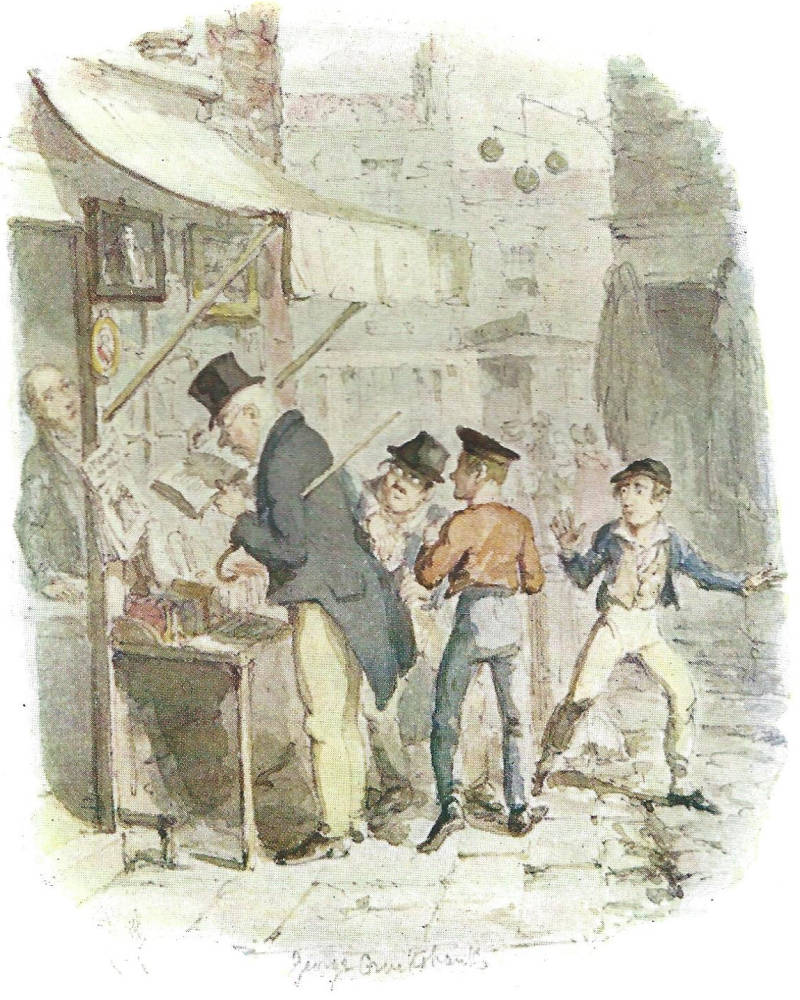

Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work — the fifth steel engraving and later a watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, first published in volume by Richard Bentley after its July 1837 appearance in Bentley's Miscellany, Chapter X. 4 ½ by 3 ¾ inches (11.5 cm by 9.5 cm), vignetted, facing page 50 (originally leading off the monthly instalment). Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1903 chromolithograph. Note: As a consequence of the death of his beloved young sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, Dickens failed to produce a June instalment. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated in the 1846 edition

The old gentleman was a very respectable-looking personage, with a powdered head and gold spectacles. He was dressed in a bottle-green coat with a black velvet collar; wore white trousers; and carried a smart bamboo cane under his arm. He had taken up a book from the stall, and there he stood, reading away, as hard as if he were in his elbow-chair, in his own study. It is very possible that he fancied himself there, indeed; for it was plain, from his abstraction, that he saw not the book-stall, nor the street, nor the boys, nor, in short, anything but the book itself — which he was reading straight through: turning over the leaf when he got to the bottom of a page, beginning at the top line of the next one, and going regularly on, with the greatest interest and eagerness.

What was Oliver's horror and alarm as he stood a few paces off, looking on with his eyelids as wide open as they would possibly go, to see the Dodger plunge his hand into the old gentleman's pocket, and draw from thence a handkerchief! To see him hand the same to Charley Bates; and finally to behold them, both, running away round the corner at full speed.

In an instant the whole mystery of the handkerchiefs, and the watches, and the Jewels, and the Jew, rushed upon the boy's mind. He stood, for a moment, with the blood so tingling through all his veins from terror, that he felt as if he were in a burning fire; then, confused and frightened, he took to his heels; and, not knowing what he did, made off as fast as he could lay his feet to the ground. [Chapter X, "Oliver becomes better acquainted with the characters of his new associates; and purchases experience at a high price. Being a short, but very important chapter, in this history," pp. 42-43]

Commentary: Providence Brings Oliver to Mr. Brownlow

The theft of Mr. Brownlow continues his "progress" through criminal underworld in the tradition of Fielding's Jonathon Wilde and William Hogarth's The Harlot's Progress. For the London readers of the 1830s the scene would have seemed frighteningly real as it draws the viewer's attention to those executing the crime, since the light-fingered street boys would often abscond with the fruits of their crime without even being detected. In this case, the boys are pilfering the gentleman's tailcoat pocket, so that the victim, so thoroughly absorbed in reading, does not apprehend what is transpiring. Significantly in Cruikshank's illustration the bookseller (left) is observing with growing alarm what is happening to his customer, so that later he will be able to exonerate Oliver, despite magistrate Fang's determination to punish the petty theft to the full extent of the law. By sheer coincidence (or Fate) the victim of the petty theft is associated with the buried life of Oliver's mother in that he is the boy's great uncle, and was the best friend of Edwin Leeford, Oliver's natural father.

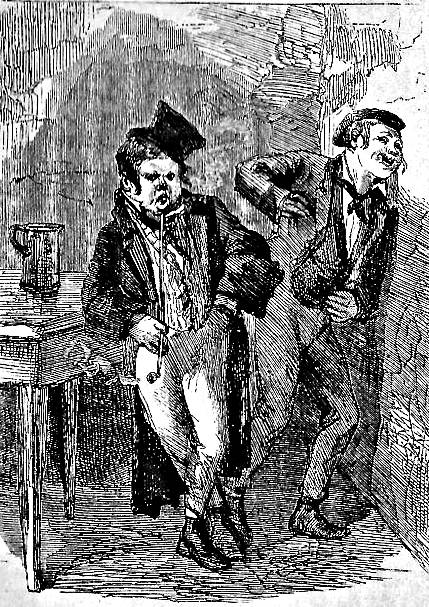

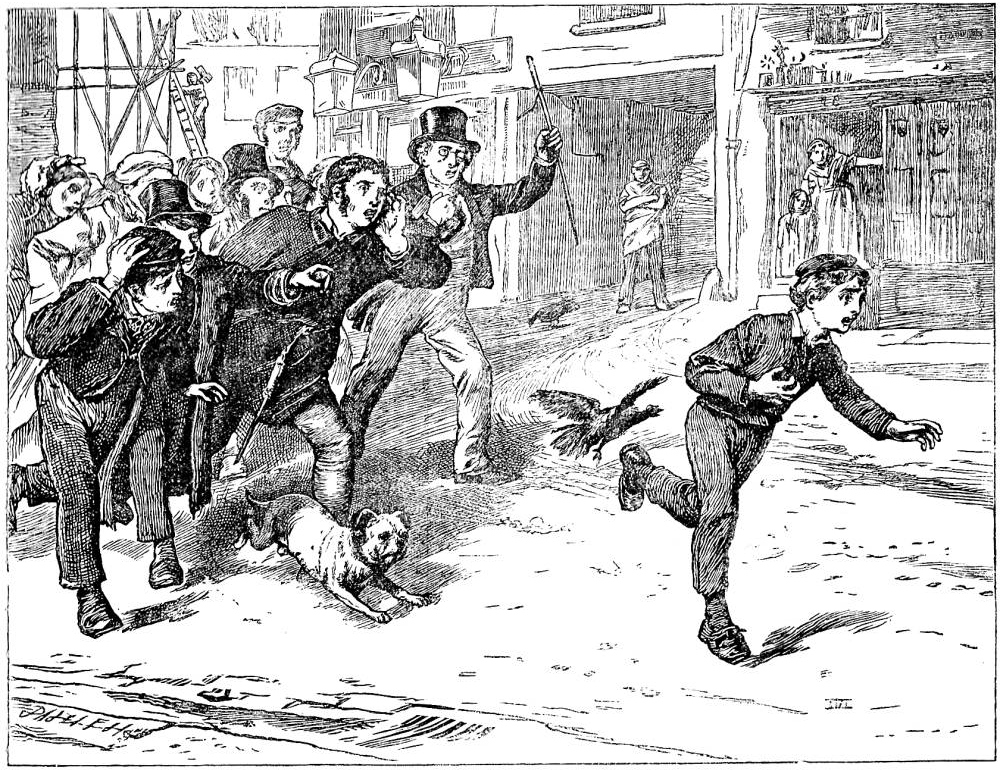

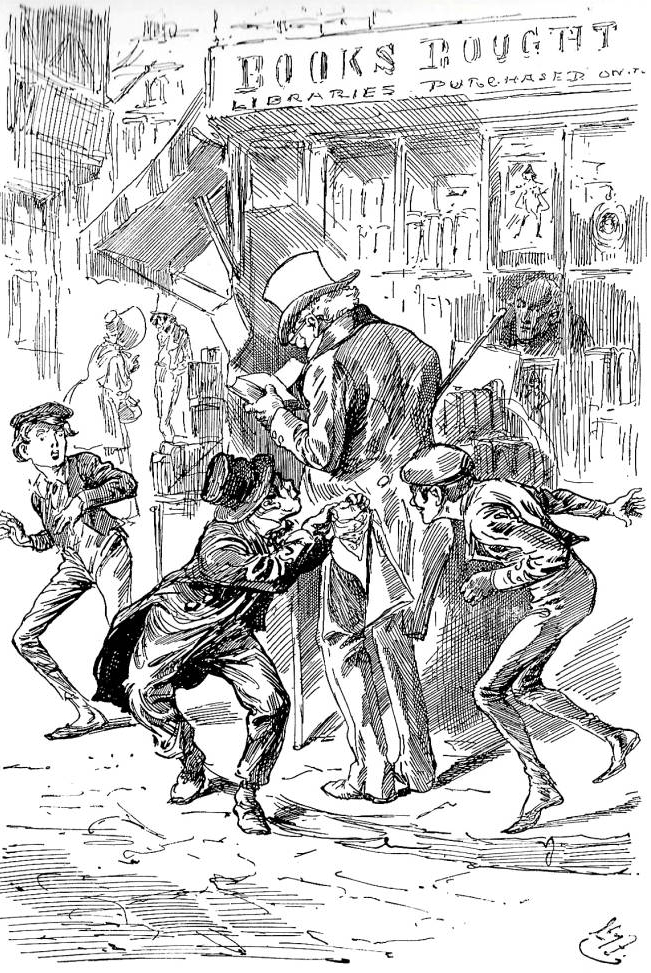

Oliver is still naive about adults, despite ill-treatment by Bumble, the parish beadle, and the overfed master of the workhouse, and the Sowerberry establishment, until he assesses Fagin's motives as he witnesses Jack and Charley pick the pocket of a gentleman as he browses through books at a stall in the Green at Clerkenwell. Significant as this epiphany is in Oliver's descent into the criminal underworld of the East End of London, the other illustrators seem to have been reluctant to have their work compared to Cruikshank's, and so reflected upon the incident in different ways: for example, while Eytinge offers a dual character study of the malefactors, Charley Bates and the Dodger, Mahoney depicts the hue and cry after Oliver, in which ironically, both Charley and Jack Dawkins join. Furniss explores the same scene selected for illustration by Dickens and Cruikshank jointly, but places Oliver, startled, in the background, and develops the dramatic scene in the round, so to speak, foreground the Dodger and Charley, and placing Brownlow with his back to the reader.

Relevant Illustrations from Various Editions (1867, 1871, 1886 and 1910)

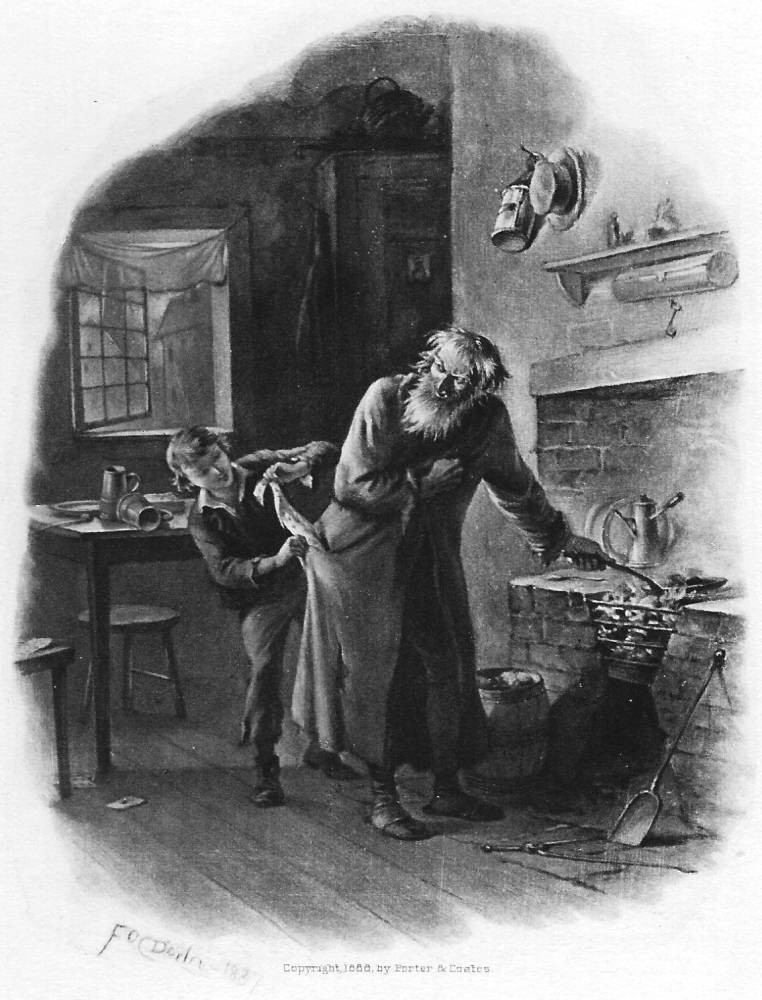

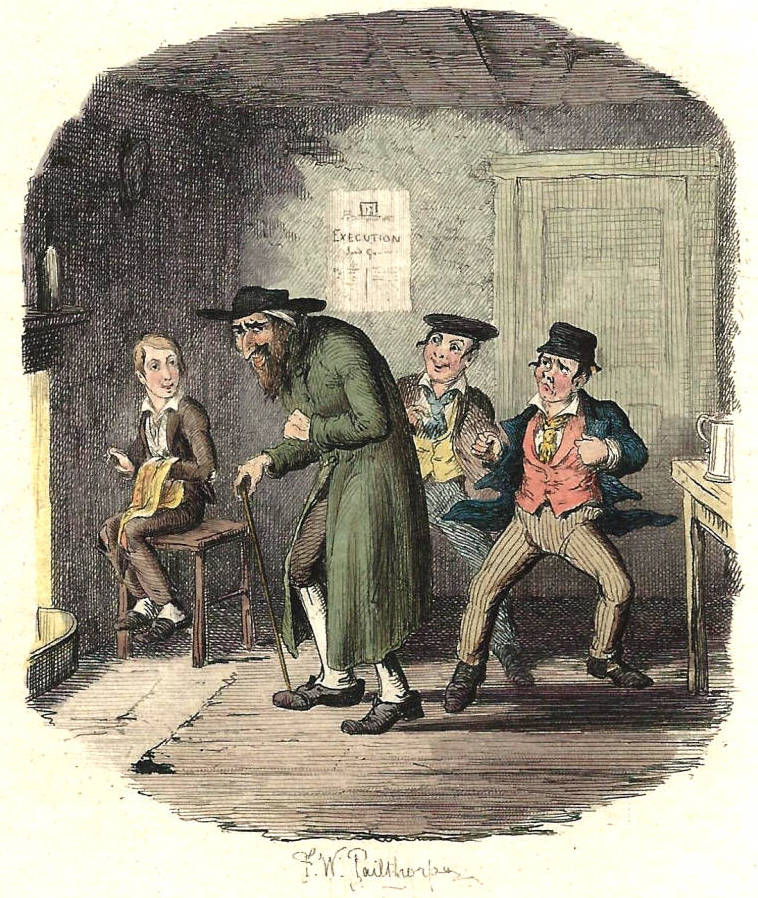

Left: F. O. C. Darley's Oliver and Fagan [sic] (1888). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates (1867). Right: F. W. Pailthorpe's "extra" illustration of Fagin's preparatory exercise for Oliver, The merry old Gentleman's pretty little game (1886). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration (1871) "Stop thief!". Right: Harry Furniss's Oliver's eyes are opened (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro) and George Cruikshank. "Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work." Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmetts Insurrection in 1803]. London: A. & C. Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Page 20.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Created 15 April 2019 Last updated 10 January 2022