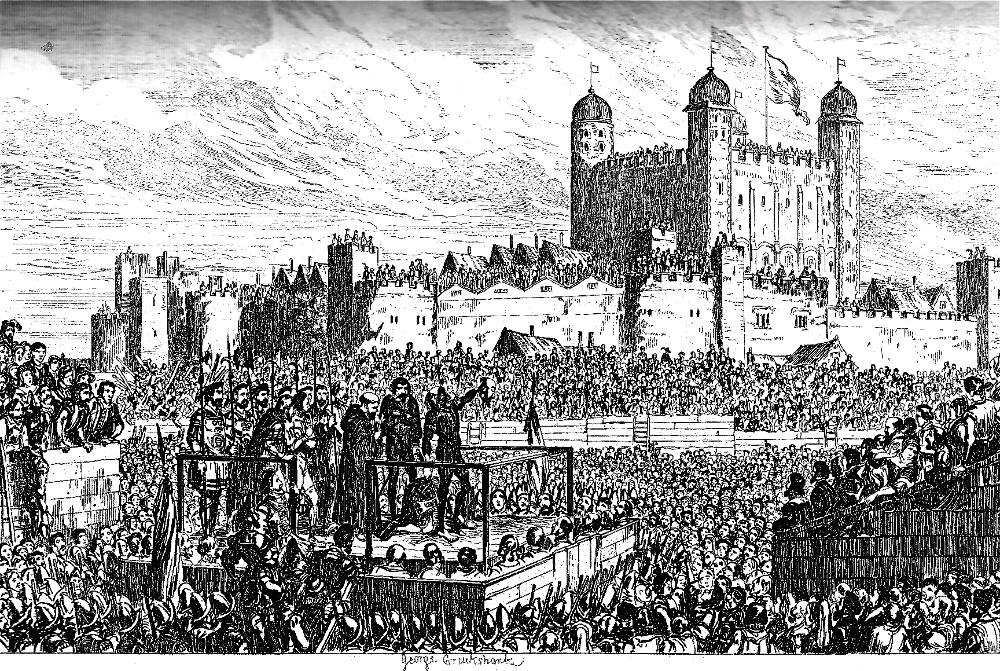

Execution of The Duke of Northumberland upon Tower Hill. — George Cruikshank. May 1840 number. Thirty-seventh illustration in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. Steel-engraving 9.8 cm high x 14.7 wide, framed, facing p. 160. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Preceded by a band of arquebussiers, armed with calivers, and attended by the sheriffs, the priest, and Simon Renard, Northumberland marched slowly forward. At length, he reached the scaffold. It was surrounded by seats, set aside for persons of distinction; and among its occupants were many of his former friends and allies. Avoiding their gaze, the Duke mounted the scaffold with a firm foot; but the sight of the vast concourse from this elevated point almost unmanned him. As he looked around, another murmur arose, and the mob undulated like the ocean. Near the block stood Mauger, leaning on his axe; his features concealed by a hideous black mask. On the Duke's appearance, he fell on his knees, and, according to custom, demanded forgiveness, which was granted. Throwing aside his robe, the Duke then advanced to the side of the scaffold, and leaning over the eastern rail, thus addressed the assemblage:

"Good people. I am come hither this day to die, as ye know. Indeed, I confess to you all that I have been an evil liver, and have done wickedly all the days of my life; and, of all, most against the Queen’s highness, of whom I here openly ask forgiveness,” and he reverentially bent the knee. “But I alone am not the original doer thereof, I assure you, for there were some others who procured the same. But I will not name them, for I will now hurt no man. And the chief occasion that I have erred from the Catholic faith and true doctrine of Christ, has been through false and seditious preachers. The doctrine, I mean, which has continued through all Christendom since Christ. For, good people, there is, and hath been ever since Christ, one Catholic church; which church hath continued from him to his disciples in one unity and concord, and so hath always continued from time to time until this day, and yet doth throughout all Christendom, ourselves alone excepted. Of this church I openly profess myself to be one, and do steadfastly believe therein. I speak unfeignedly from the bottom of my heart. And I beseech you all bear witness that I die therein. Moreover, I do think, if I had had this belief sooner, I never should have come to this pass: wherefore I exhort you all, good people, take example of me, and forsake this new doctrine betimes. Defer it not long, lest God plague you as he hath me, who now suffer this vile death most deservedly."

Concluding by desiring the prayers of the assemblage, he returned slowly, and fixing an inquiring look upon Renard, who was standing with his arms folded upon his breast, near the block, said in a low tone, "It comes not."

"It is not yet time," replied Renard.

The Duke was about to kneel down, when he perceived a stir amid the mob in front of the scaffold, occasioned by some one waving a handkerchief to him. Thinking it was the signal of a pardon, he paused. But he was speedily undeceived. A second glance showed him that the handkerchief was waved by Gunnora, and was spotted with blood.

Casting one glance of the bitterest anguish at Renard, he then prostrated himself, and the executioner at the same moment raised his hand. As soon as the Duke had disposed himself upon the block, the axe flashed like a gleam of lightning in the sunshine, — descended, — and the head was severed from the trunk.

Seizing it with his left hand, Mauger held it aloft, almost before the eyes were closed, crying out to the assemblage, in a loud voice, "Behold the head of a traitor!"

Amid the murmur produced by the released respiration of the multitude, a loud shriek was heard, and a cry followed that an old woman had suddenly expired. The report was true. It was Gunnora Braose. [Chapter VII. — How the Duke of Northumberland was beheaded on Tower Hill," pp. 159-160]

Commentary

Once again in an illustration that imitate a large oil painting Cruikshank reveals his aspiration to be the creator of canvasses celebrating great moments in English history. Although both the frontispiece and title-page vignette likewise reflect this aspiration, here the forty-eight-year-old illustrator, treats his subject with great seriousness. The May 1840 canvas of a significant historical event prepares the reader for the culminating illustrations which serve as the frontispiece and title-page vignette, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey at Tower Green and The Execution of Lord Guildford Dudley on Tower Hill (December 1840).The huge numbers of spectators imply the Duke's unpopularity, and reinforce his misgivings about his ever escaping the dread sentence even should he receive a last-minute reprieve from the testy young monarch. Cruikshank places Gunnora Braose and Simon Renard in significant positions so that the reader can readily distinguish them.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 12 October 2017