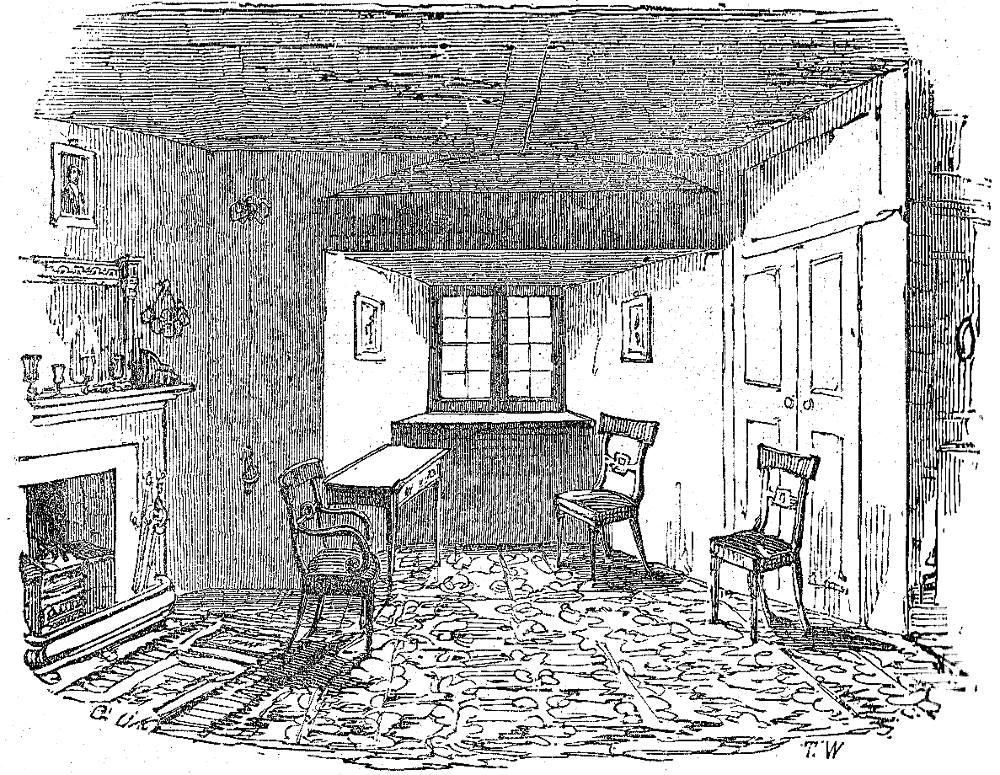

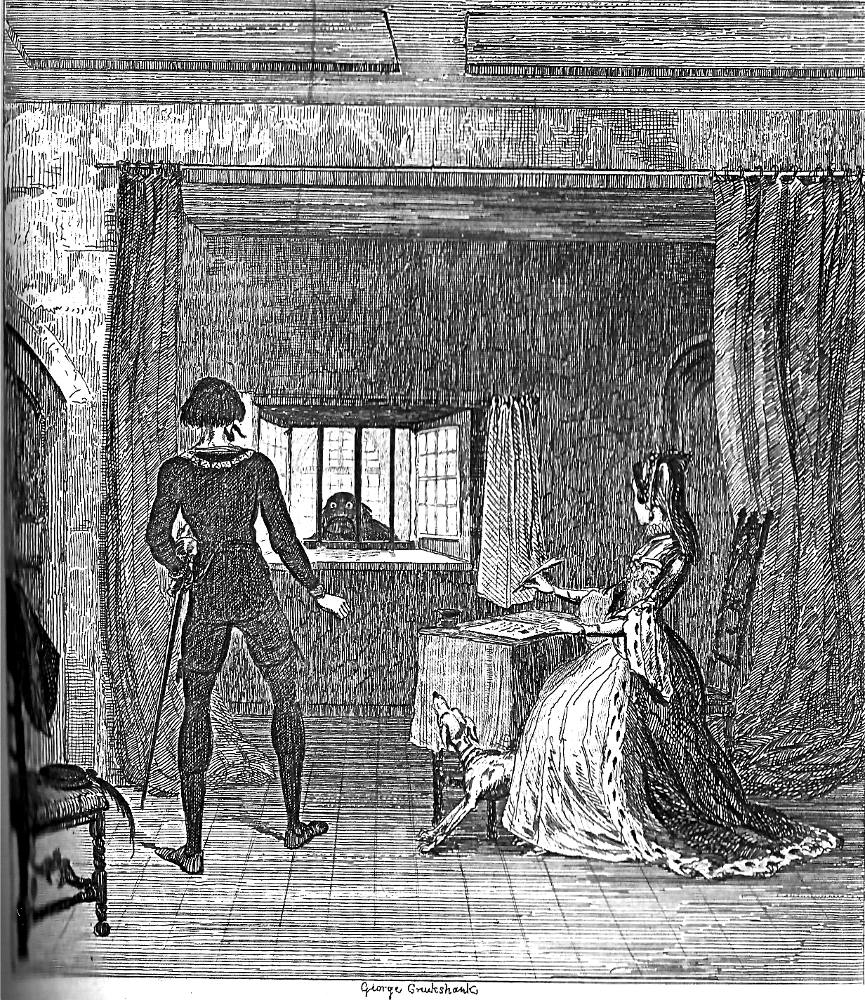

North Side of the Room in which the Princes were Murdered. — George Cruikshank. The eleventh instalment, November 1840 number. Eighty-third illustration and and forty-ninth wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXXIII. 7.6 cm high x 9.7 cm wide, vignetted, bottom of page 352: running head, "Mary Signs Jane's Death-warrant." What tourist, visiting the staid Victorian parlour, would credit that such events as the murder of the Princes and the signing of Lady Jane Grey's execution order occurred in this very room? However, the resemblance between the room in 1840 and that room as Cruikshank imagines it in 1554 is undeniable. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

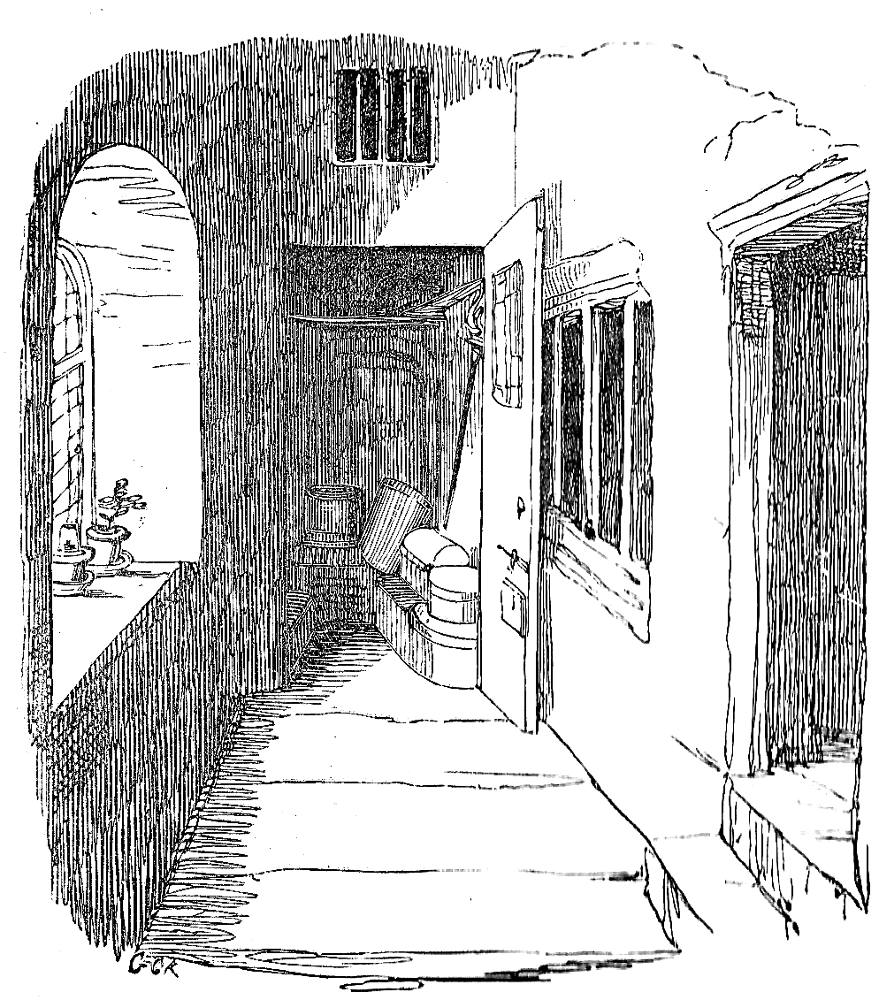

Repressing a cry of alarm, she called Renard's attention to the object, when she was equally startled by his appearance. He seemed transfixed with horror, with his right hand extended towards the mysterious object, and clenched, while the left grasped his sword. Suddenly, he regained his consciousness, and drawing his rapier, dashed to the door,—but ere he could open it, the mask had disappeared. He hurried along the passage in the direction of the lieutenant’s lodgings, when he encountered some one who appeared to be advancing towards him. Seizing this person by the throat and presenting his sword to his breast, he found from the voice that it was Nightgall. [Chapter XXXIII. — "How Nightgall was Bribed by De Noailles to Assassinate Simon Renard; And How Jane's Death-warrant was Signed," pp. 352]

Illustrations of the Bloody Tower in Chapter XXXIII

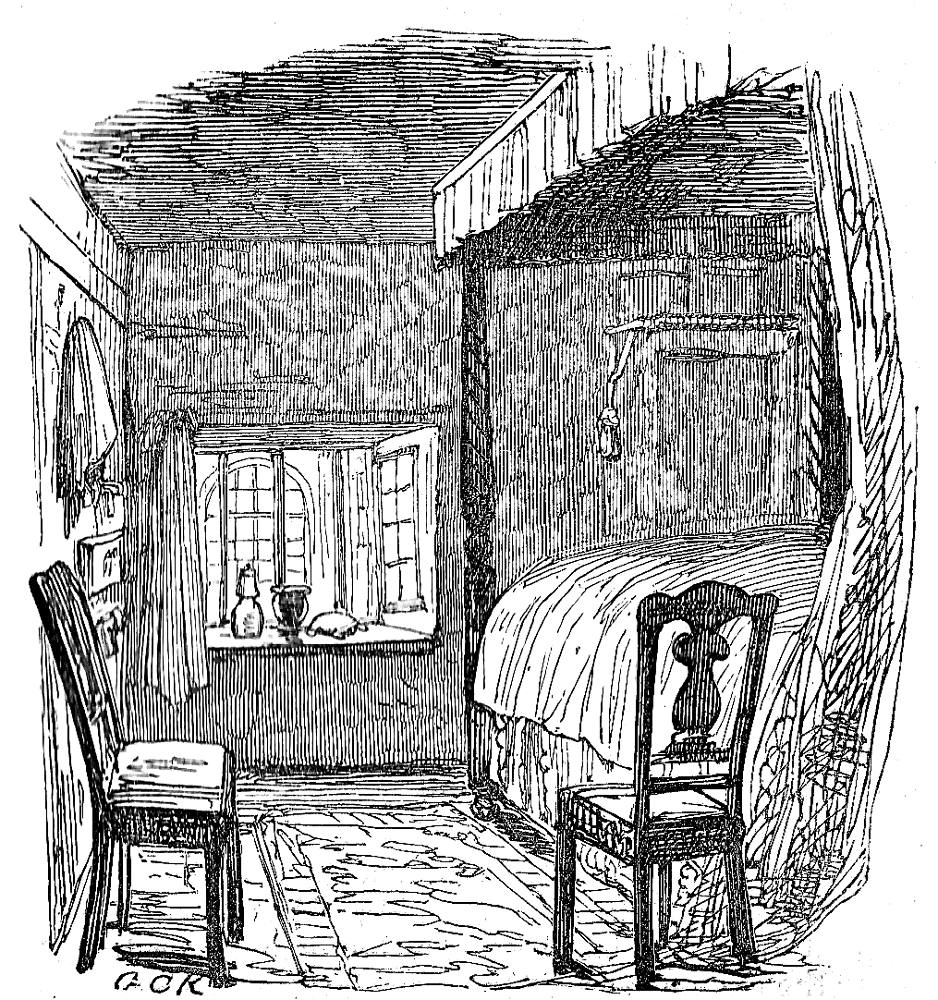

Left: The wood-engraving of the room where by tradition the sons of Edward IV were murdered by agents of the Duke of Gloucester, South Side of the Room in which the Young Princes were Murdered as it looked in 1840. Centre: North Side of the Room in which the Princes were Murdered (November 1840). Right: The imagined scene as Renard and Mary deliberate over consigning her cousin to the scaffold for treason, The Death-Warrant (November 1840). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Commentary: Interweaving Fact and Fiction

Cruikshank juxtaposes a wood-engraving of the quietly furnished domestic space as it existed in 1840 (p. 350) with Ainsworth's dramatic scene involving Mary Tudor, the Spanish ambassador, Simon Renard, and the mysterious mask at the window. In fact, this tidy Victorian parlour is the last of three such present-day scenes that are sharply at variance with the sanguine associations of the suite of rooms which the machiavellian Simon Renard occupies in the novel, which, as the juxtaposition of the wood-engravings and the steel-engraving suggest, blends a strictly historical strain (the execution of Lady Jane Grey) and a fictional element involving the jailor Nightgall, his jealousy of Cuthbert Cholmondeley, and his lust for Alexia and Cicely. As the text in these pages stipulates, Mary has been working on correspondence at the writing desk in the ambassador's apartment in the upper storey of the Bloody Tower, receiving but not always acceding to Renard's advice regarding impending executions. She has, however, reluctantly just signed the death-warrants for her cousins, Lady Jane and Lord Guildford Dudley as their continued existence poses a threat both to her rule and the continued existence of the Roman Catholic Church in England.

In the culminating steel-engraving Cruikshank fails to invest Renard's apartment with the ominous overtones appropriate to either the scene in which Nightgall, disguised, interrupts the discussion over whether to execute Jane. Tradition holds that in this very room the Duke of Gloucester's henchman Sir James Tyrell murdered the young "Princes in the Tower" in June 1483. The discovery of their skeletons in a stone staircase on the south side of the White Tower in 1674 may have resolved their mysterious disappearance, although it failed to confirm the tradition that the sons of Edward IV died in this very room — although the Church of England has continued to refuse to allow either set of remains to be subjected to DNA analysis to identify them as the remains of the princes. Close to the writing of the novel, the draining of the Tower moat between 1830 and 1840 exposed a great many bones, some of which were attributed to the missing princes, so that the story continued to be of some topical interest at the time that Ainsworth was writing the novel. Nightgall's decision to accept the French ambassador's commission to assassinate Renard proves his undoing.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 28 October 2017