These illustrations for George Meredith's The Adventures of Harry Richmond originally appeared in The Cornhill Magazine, 1870/1, and were reprinted in 1909 in Hammerton (see bibliography). Scans, captions and commentary by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Roy carrying Harry away from Riversley, Hammerton, facing p. 136.

No illustration could ever quite do justice to Richmond Roy, the extraordinary father-figure whose presence dominates The Adventures of Harry Richmond. This is because he looms so very large, not only in the illustration above, but in this whole narrative. He is seen almost throughout as his son sees him, diminishing only gradually as Harry gains in years and wisdom. The process begins here, when his father insists on taking him as a young boy from his father-in-law — Harry's maternal grandfather, Squire Beltham, at his estate, Riversely. It is far from complete until very near the end. George Du Maurier's illustration is perhaps the nearest any illustrator could come to evoking the charisma of Harry's father and his contrast with the small child (taken unexpectedly from his cosy bed and exposed to the enormous mystery of the world) on whom his father makes such an impact.

Left: Harry's Meeting with the Princess Ottilia, Hammerton, facing p. 144. Right: Richmond Roy with His Son in "High Germany", Hammerton, facing p. 152.

After their adventures together Harry is left at school, missing his father, and eventually sets off to find him again, now physically "hunting [his] father in an unknown country" (Ch. 5, 51). Here he is on the left, crossing Germany with his schoolfellow Gus Temple, and meeting a youthful Princess Ottila in the woods. J. A. Hamilton finds this to be "on more conventional lines" than the first illustration, but still "still instinct with grace and movement" (377). Having tracked down his father at last, he is now ensconced with Gus and Richmond in a "long saloon ornamented with stags' horns and instruments of the chase, tusks of boars, spear-staves, boar-knives, and silver horns," in the margravine's "beautiful villa" in the little German principality of Sarkeld (Ch. 18, 203). Their immediate surroundings suggest both Richmond's gentlemanly pretensions, and, more specifically, Harry's long pursuit of his elusive father. Now that Harry's horizons have started to broaden, he can see his father somewhat more clearly. He is beginning to analyse, too, what he finds so affecting in him:

I used as a little fellow to think him larger than he really was, but he was of good size, inclined to be stout; his eyes were grey, rather prominent, and his forehead sloped from arched eyebrows. So conversational were his eyes and brows that he could persuade you to imagine that he was carrying on a dialogue without opening his mouth. His voice was charmingly clear; his laughter confident, fresh, catching, the outburst of his very self, as laughter should be. Other sounds of laughter were like echoes. [Ch. 18, 209]

There is a touch here of Meredith's hunting symbolism, in the array of pointed implements beside the screen in the backround. Du Maurier has caught the physical aspects of Richmond's appearance very well. More importantly he has also caught the way he begins to exert all his old charm over his son. The focus is on his relaxed, indolent, supremely assured pose, his fine pair of legs stretched out elegantly so as to occupy more than half the foreground. With his characteristic panache, Richmond handles the guitar like a showman, seeming transported by his own music although he has merely "flipped a string" and is strumming the instrument idly. He is nothing if not a performer. And Harry is the ideal audience. He leans forward as he listens, equally rapt, feeling his old "active belief and vivid delight in his presence" come flooding back. Temple, lounging more casually on the back of Harry's chair, also feels a "growing admiration of him" (Ch.18, 208).

All this comes in the wake of Richmond's latest, most daring piece of showmanship. He had impersonated a statue commissioned at short notice by the margravine in memory of her great ancestor, Prince Albrecht. It was a role in which Richmond had greatly fancied himself: "The wonder of it was my magificent resemblance to the defunct," he tells Harry proudly (Ch. 18, 210). Indeed, he had carried it off triumphantly until his surprise at seeing Harry at the unveiling made him break his pose, dismount from the bronze horse (it was an equestrian statue), and reveal the subterfuge. He is now in disgrace, and must leave forthwith. Since, uniquely among Meredith's novels, this is a first-person narrative, we learn that the moment he goes off to pack, some of his hold over his son loosens: "Strange to say, I lost the links of my familiarity with him when he left us on a short visit to his trunks and portmanteaux, and had to lean on Temple" (Ch. 18, 209). Thus Du Maurier has seized on a special moment of rapport which does not last, but gives way to more confused and disturbing feelings. Harry undergoes a sort of deliquescence. As the relationship begins to disintegrate further, Harry must find his own purpose, his own identity, and above all learn to stand on his own two feet.

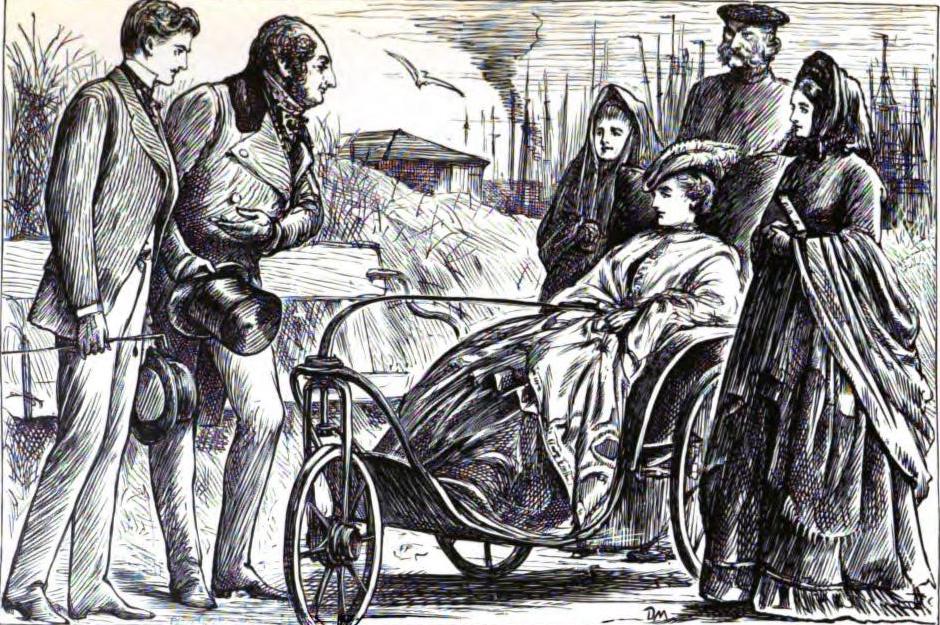

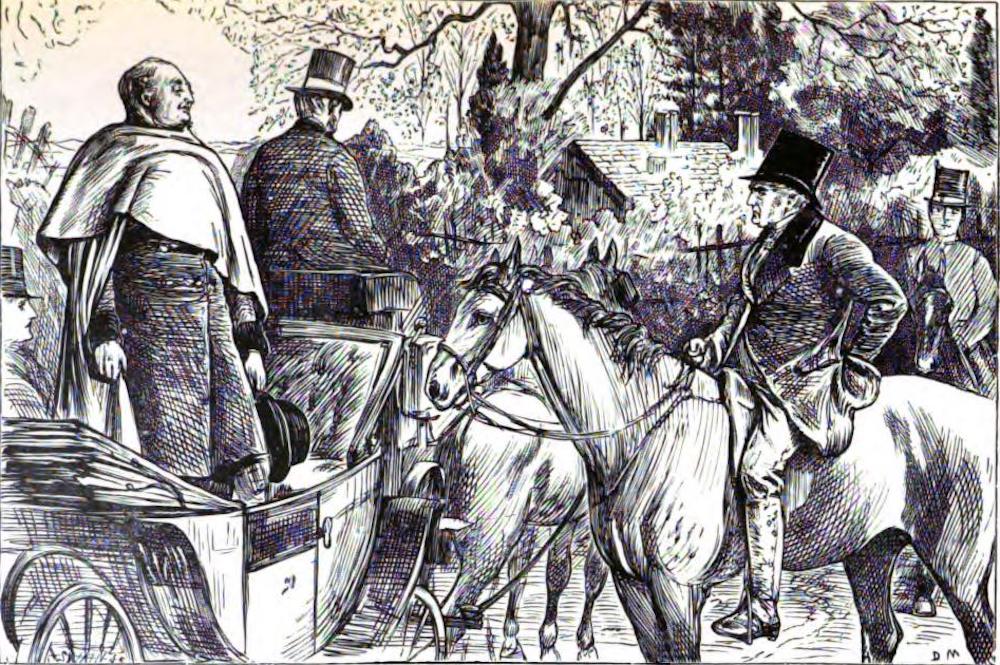

Left: Roy Re-introduces Harry to Ottilia at Ostend, Hammerton, facing p. 160. Right: Richmond Roy Meets Squire Beltham, Hammerton, facing p. 168.

Harry's love for Ottilia is doomed. She has always seemed like someone in a fairytale, or even a goddess, removed from his reality, as Du Maurier depicts her here. She eventually marries a German Prince, after the scheme for her to marry Harry falls through when the Squire discovers that his daughter, Dorothy, has had to pay off Roy Richmond's debts, and refuses to play his part in it. The two men who have dominated Harry's life are seen together in Du Maurier's illustration, Richmond Roy standing proudly aloof, and Squire Beltham looking at hin balefully.

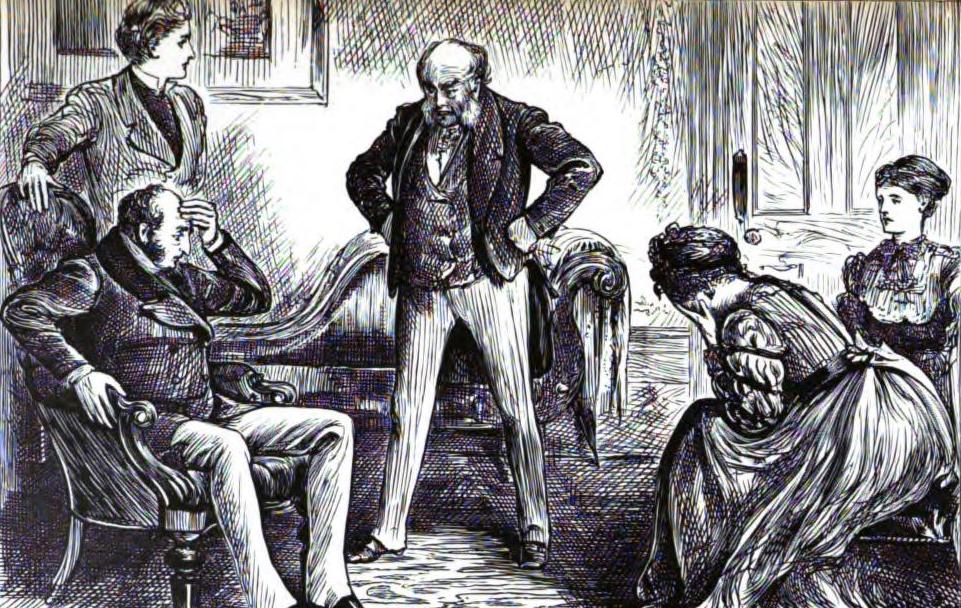

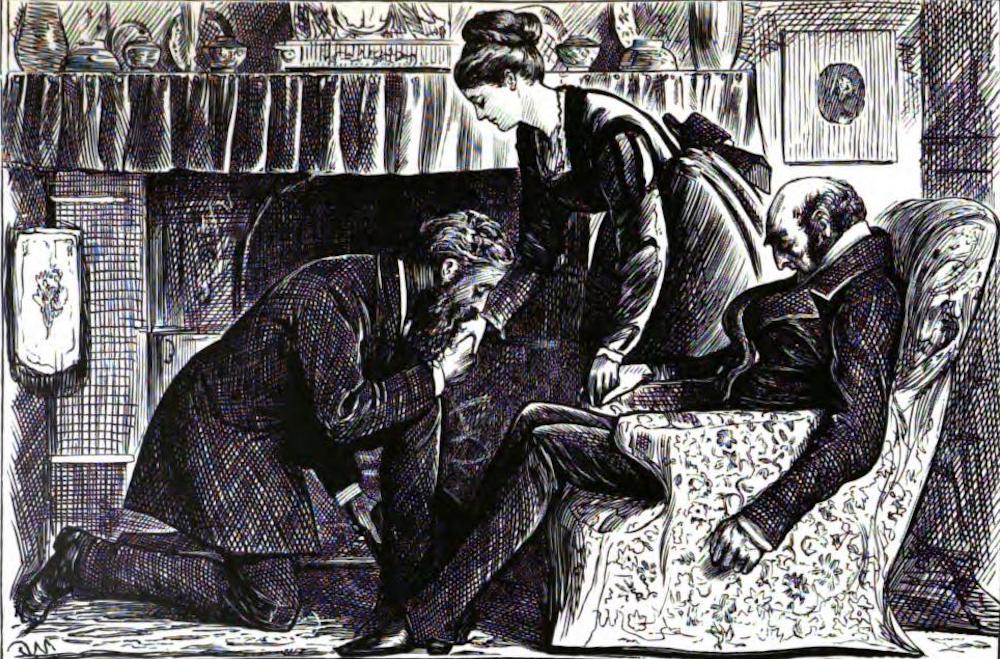

Left: Squire Beltham Has His Last Innings, Hammerton, facing p. 176. Right: Janet Ilchester with Harry and His Father, Hammerton, facing p. 184.

Du Maurier shows the two men at loggerheads with each other, as the scheme for Harry's marriage to Ottilia collapses. But another plan also falls through — Harry's third cousin, Janet Ilchester, was to marry a Marquis, who drowned just before the ceremony. After this, Harry, having realised that he loves her, is able to propose to her at last, and is accepted. Du Maurier's illustration of Harry proposing to Janet, in the domestic setting of hearth and home, suggests not only that they will forge their own future together, but that Janet, who has been looking after his already ailing father, will be the one to keep them grounded. In the end, Roy Richmond implodes, or, rather, explodes. This is the result of one of his own fantastic schemes — to welcome Harry and Janet home with a gigantic firework display that goes wrong.

Links to Related Material

- George Meredith (homepage)

- George Meredith and His Illustrators, by J. A. Hammerton

- Evan Harrington, The Adventures of Harry Richmond, and the Evolutionary Debate of the 1860s

Bibliography

Hammerton, J. A. (Sir). George Meredith in Anecdote and Criticism. London: Grant Richards; New York: M. Kennerley, 1909. Internet Archive, from a book in the New York Public Library. Web. 16 April 2023.

Meredith, George. The Adventures of Harry Richmond. The Memorial Edition. London: Constable,1909.

Last modified 12 February 2010