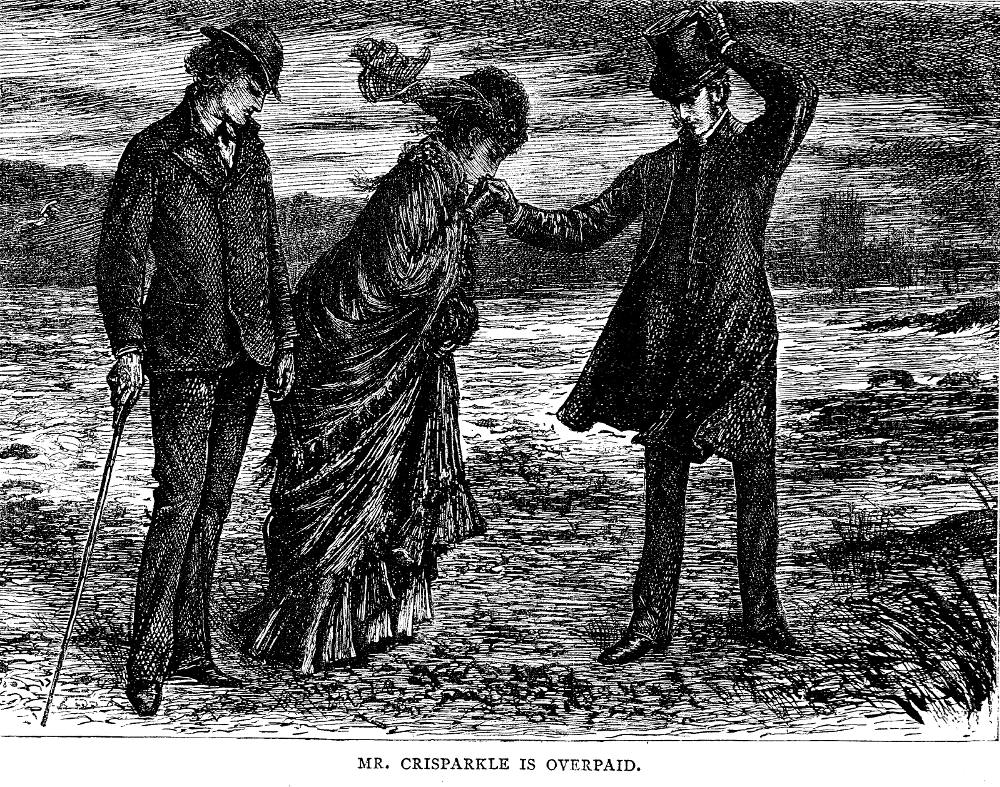

Mr. Crisparkle is Overpaid, sixth illustration by Sir Samuel Luke Fildes for the Household Edition. First plate for the June 1870 serial instalment. Facing page 63 for The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). 16.4 cm wide by 10 cm high (4 by 5 ⅜ inches), framed and horizontally mounted in Chapter X, "Smoothing the Way." Page 48: Headline in the Household Edition (1879): "Mr. Jasper's Diary" (47). [Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: The Rev. Crisparkle meets Helena and Neville on the Beach

She [Helena] took the hand he offered her, and gratefully and almost reverently raised it to her lips.

"Tut!" said the Minor Canon, softly, "I am much overpaid!" and turned away. [Chapter X, "Smoothing the Way," p. 46 in the Household Edition

Commentary: The Developing Relationship between Helena Landless and Rev. Crisparkle

In a stiff breeze that blows through the scene from right to left, the Reverend Mr. Septimus Crisparkle has descended from "his favorite fragment of ruin" above to join Helena and her twin-brother, Neville, who have just passed before him where the river meets the sea. Although it does not figure in Dickens's description of the scene, Fildes has included Cloisterham Cathedral on the horizon behind the Reverend Septimus Crisparkle, upper right, perhaps to provide the viewer with a point of reference that reveals at a glance how far these three are from the town. So emotionally extravagant a gesture would be singularly out of place in the streets of the town. Consistent with the letter-press, the shore is strewn with clumps of seaweed washed up by the last tide, and one has a sense of a "wild and noisy sea" to the right. One must exercise considerable suspension of disbelief in accepting the fact that the trio's conversation is conducted under such tempestuous circumstances for some six pages of text!

The focus of the scene, however, is not the picturesque seascape but the developing relationship between Helena and Crisparkle, centre; in contrast, Neville is but faintly realised in comparison to the prominence which Fildes has accorded him in the two previous plates. We have, of course, already encountered all three characters in the third plate, At the Piano in the May 1870 instalment, but there Fildes revealed little of Crisparkle's face (shown in profile), and he seemed to be focusing on the pianist rather than the beautiful colonial standing to one side of the piano in the communal scene. In Neville's calm demeanor we detect none of the "sullen, angry, and wild" disposition revealed only moments before when he was discussing Drood's supposedly callous, neglectful treatment of Rosa.

Whereas Helena is well-bundled up against the wind, Neville in the illustration is perhaps not sufficiently dressed for a walk which Dickens describes as "too exposed and cold for the time of year." Neither the brother nor the sister looks directly at the Minor Cannon, who seems dressed for a formal, church function rather than an afternoon's physical recreation (perhaps he is thus dressed to make the clear to the viewer his clerical function in this scene, in which he enunciates the doctrine of forgiveness). Neville's gaze is downcast, implying perhaps not so much depression as a sense of embarrassment at his recent conduct in John Jasper's room. Helena avoids looking directly at Mr. Crisparkle from a sense of humility and gratitude at the Reverend's having defended her brother's reputation publicly and having offered to make peace between the young men. Crisparkle counsels spiritual "submission" by arguing that Neville should concede that he was at fault. Certainly, Fildes is dramatizing the submission of brother and sister to the Minor Canon while suggesting that Helena's kiss is at least partly motivated by a devotion not entirely Christian. Fildes makes clear Helena's veneration of the pious clergyman for his charitable attitude towards her brother, even as the artist shows the physical resemblance between the twins in terms of their profiles, complexions, hair, and height. However, Fildes has dressed Neville in a costume different from that which he wore in the two previous illustrations, and generalizes his features, perhaps to place the focus on the other two characters.

Although as one of the "New Men of the Sixties" Fildes tended to eschew the visual symbolism that characterized the work of the previous generation of illustrators, notably George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), Neville's cane (which Dickens does not mention) may be more than a device for guiding the viewer's eye upward, towards Neville's head. Since the lines of his sister's skirts exactly parallel the vertical of the walking stick, this may be an artistic device for implying that she is his moral prop and emotional support. Certainly since news of his outburst in Jasper's rooms has begun to circulate, he has been very much in need of such buttressing. She has stood by him, buoying up his sinking reputation at Miss Twinkleton's, for example, and attempted to counter the general prejudice against her brother, a perception that has presumably been the consequence of John Jasper's spreading rumours against him as part of his plot to do away with his nephew and shift the blame to the volatile newcomer. That public opinion can be so easily swayed against the young colonial may be a testimonial to the devious brilliance of John Jasper. Lillian Nayder implies that the youth's tawny complexion and foreign origins may be contributing factors:

Like Collins [in The Moonstone], Dickens acknowledges the crimes of empire in Edwin Drood — most notably in his portrait of the Landlesses, a brother and sister newly arrived in England from Ceylon, who recall the Hindus of The Moonstone, and point to the disinheritance of colonized peoples. [13]

Certainly in Fildes's first plate for June 1870 we are once again very much aware of the difference between their complexions and those of the established members of provincial Cloisterham society. That he ignores their racial origins is very much to the Minor Canon's credit.

Scanned image, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Chapter 18: Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980. Pp. 221-228.

Dickens, Charles. The Mystery of Edwin Drood; Reprinted Pieces and Other Stories. With Thirty Illustrations by L. Fildes, E. G. Dalziel, and F. Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall Limited, 193, Piccadilly. 1879. Vol. 20.

Dickens, Charles, and W. E. C[risp]. The Mystery of Edwin Drood, ed. Mary L. C. Grant. New text drawings by Zoffany Oldfield. London: J. M. Ouseley, 9 John Street, Adelphi, 1914.

Fildes, Luke. Mr. Crisparkle is Overpaid. Charles Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870, London: Chapman & Hall). Rpt. Ed. David Paroissien. Penguin: London, 2002. Facing page 102.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. 22 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1879. Vol. XXII.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U. P., 2002.

Walters, J. Cuming. The Complete Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens: The History, Continuations, and Solutions (1870-1912). Illustrated by Luke Fildes and Frederic G. Kitton. London: Chapman and Hall, 1912.

Created 9 May 2005 Last updated 22 August 2025