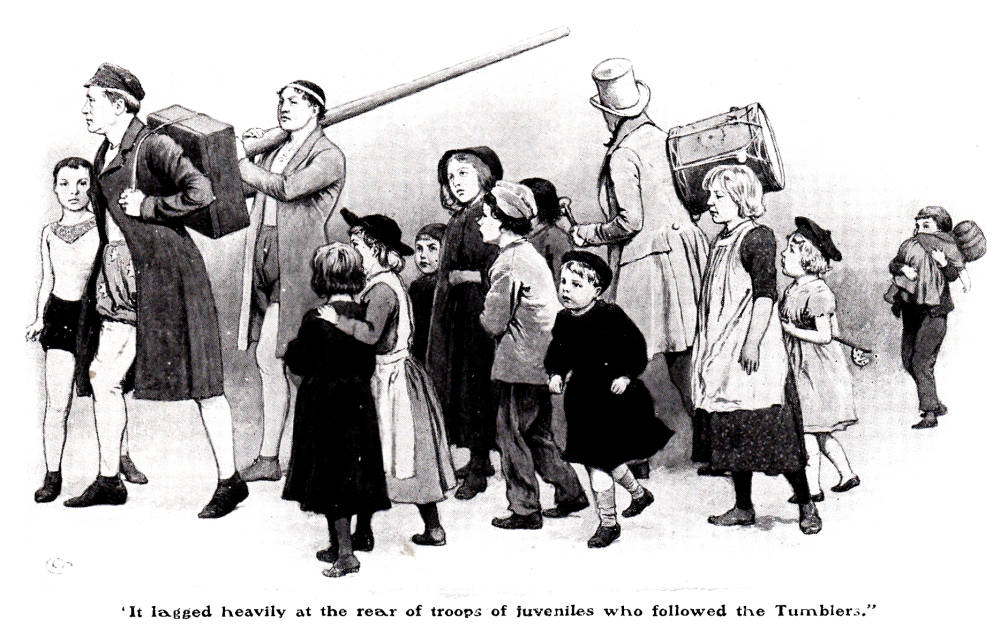

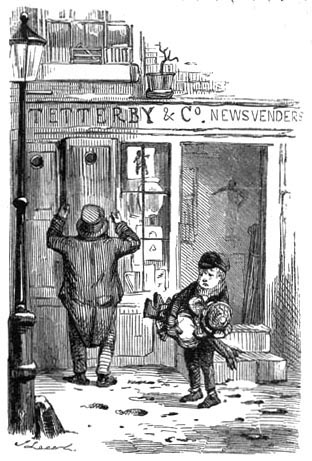

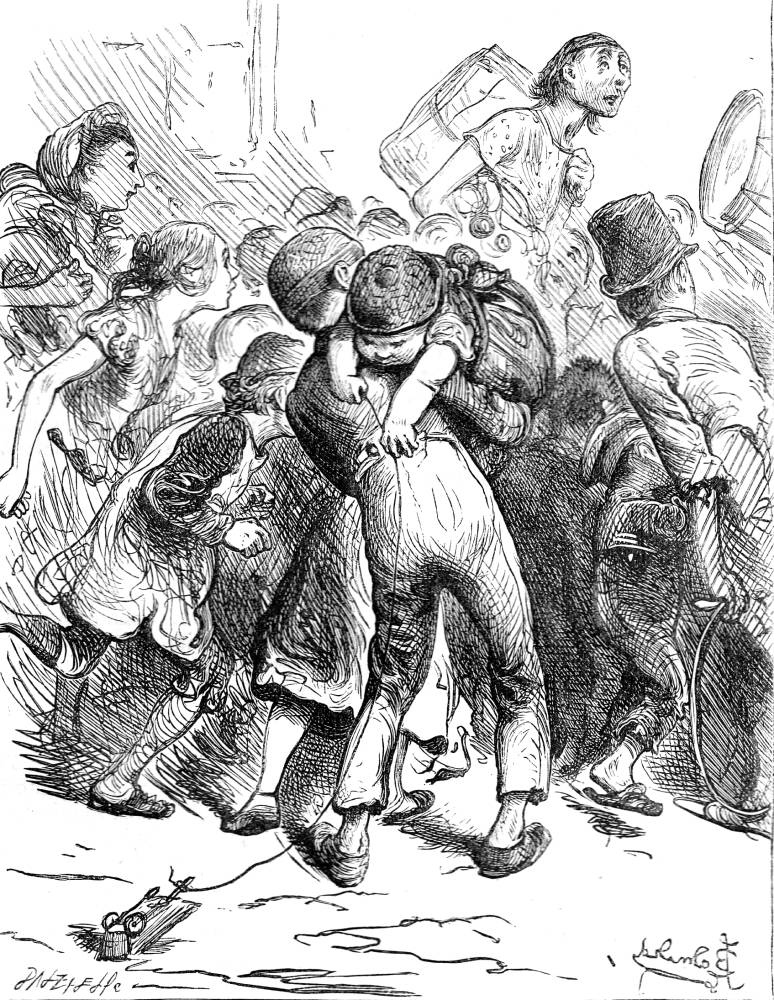

The Tumblers and Johnny Tetterby with 'Tetterby's Baby' by Charles Green. 1895. 9 x 15.3 cm, vignetted. Charles Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas Time, Pears Centenary Edition (1912), in which the plates often have captions that are different from the short titles given at the beginning of the volume in the "List of Illustrations" (15-16). For example, the series editor, Clement Shorter, has included some of the same quotation that Fred Barnard had used as a caption underneath the picture of Johnny, surrounded by street children and entertainers, staggering under the weight of his sister Sally (nicknamed "Moloch," Philistine destroyer of children), in It lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the Tumblers (see below) in the Household Edition of 1878.

The Passage Illustrated

It was a very Moloch of a baby, on whose insatiate altar the whole existence of this particular young brother was offered up a daily sacrifice. Its personality may be said to have consisted in its never being quiet, in any one place, for five consecutive minutes, and never going to sleep when required. "Tetterby's baby" was as well known in the neighbourhood as the postman or the pot-boy. It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby, and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the Tumblers or the Monkey, and came up, all on one side, a little too late for everything that was attractive, from Monday morning until Saturday night. Wherever childhood congregated to play, there was little Moloch making Johnny fag and toil. Wherever Johnny desired to stay, little Moloch became fractious, and would not remain. Whenever Johnny wanted to go out, Moloch was asleep, and must be watched. Whenever Johnny wanted to stay at home, Moloch was awake, and must be taken out. Yet Johnny was verily persuaded that it was a faultless baby, without its peer in the realm of England, and was quite content to catch meek glimpses of things in general from behind its skirts, or over its limp flapping bonnet, and to go staggering about with it like a very little porter with a very large parcel, which was not directed to anybody, and could never be delivered anywhere. ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," Pears Centenary Edition, 58; British Household Edition, 168]

Commentary

Green’s illustration, which handles perspective perfectly correctly, distributing the fifteen figures across the page and distinguishing each by gender, size, and clothing, but it fails to capture the energy inherent in Dickens's description of the children and the acrobats. Through the tights of the child (left), the package, pole, and drum of the three adult acrobats Green gives the scene an internal context, as the children follow the circus performers as their counterparts do at the opening of Dickens's 1854 novel Hard Times for These Times. The pinafores, bonnets, coats, and caps of the children seem more consistent with turn-of-the-century children's fashions, but the movement and countermovement of the composition are highly effective as the procession proceeds right to left, but the pole and the backward glancing drummer (right of centre) pull the reader's gaze towards the right and a small Johnny in perspective, lagging far behind everyone else, as if his domestic responsibilities are preventing him from joining the other children at play.

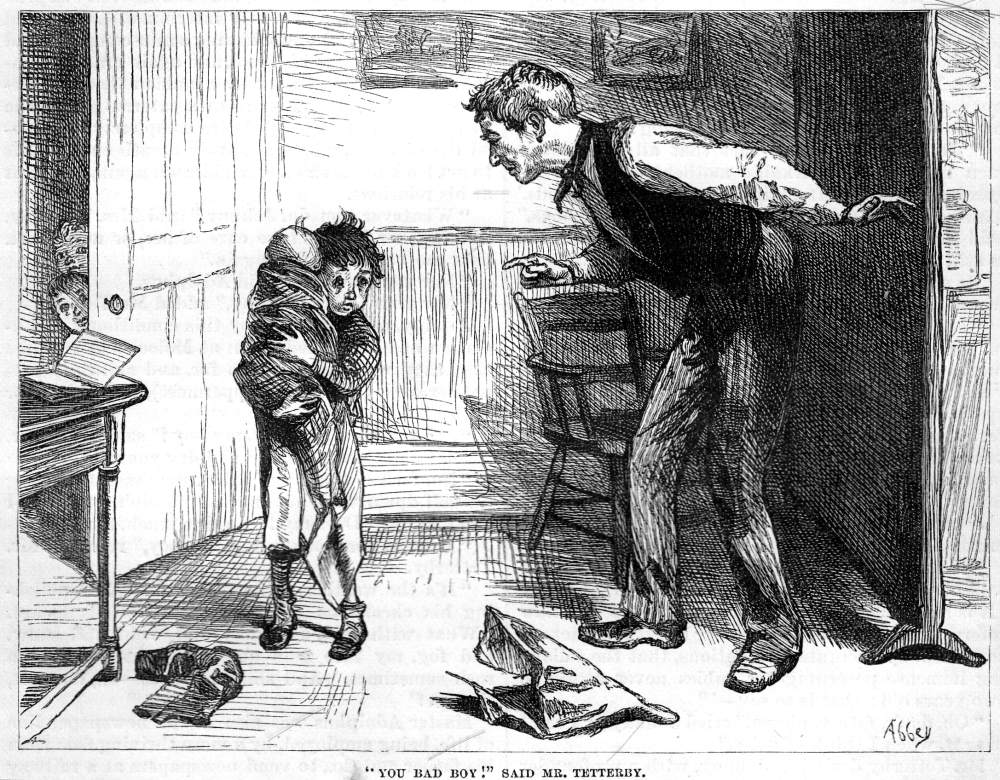

Above: Abbey's "You bad boy!" (1876) also reinforces Johnny's feeling that he is a slave to his parents and sibling.

Whereas Green presents Johnny in a panorama of street characters, both other children and acrobats, without any informing backdrop, in 1876 American illustrator E. A. Abbey combined a visual introduction of Mr. Tetterby in his shop with John Leech's Johnny and Moloch (see below) in his second illustration for the American Household Edition, "You bad boy!" said Mr. Tetterby (see below).

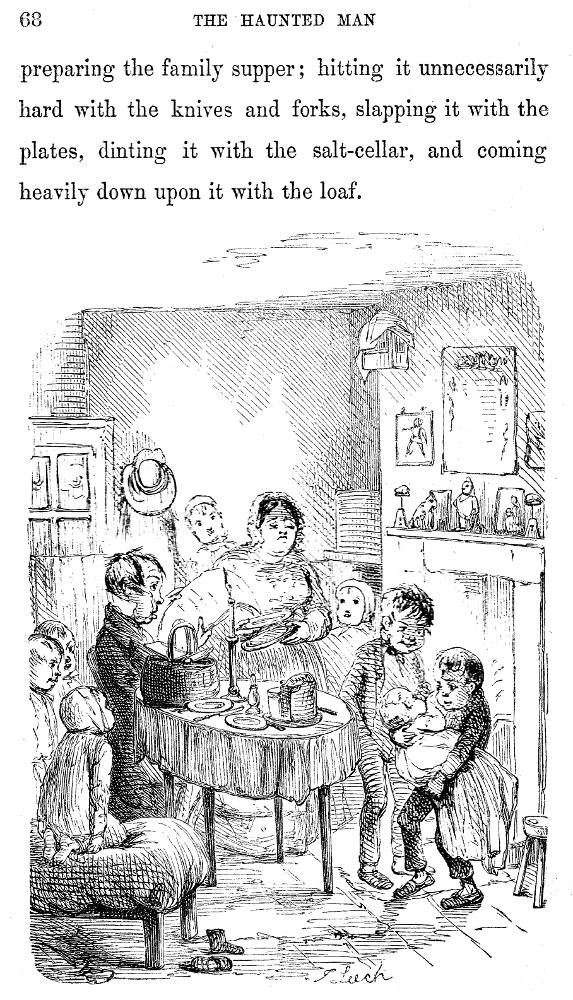

Leech's exuberant cartoon versus Barnard's and Abbey's modelled portraits and more prosaic treatments: left: Leech's The Tetterbys; centre, Leech's Johnny and Moloch; and, right, Barnard's wood-engraving of the putupon Johnny lugging Moloch, destroyer of childhood, through the streets, It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby, and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the Tumblers (1878).

However, Abbey, like Green, fails to capture either Johnny's frustration or the sheer size of the infant "Moloch." Green's interpretations of Tetterby and his youngsters lacks the detailism of Leech's densely-packed parlour scene, and is therefore less effective in communicating the text's sense of the inadvertant tyranny of the Tetterby children and of their father's feeling of being oppressed, and unable to concentrate on reading his paper in Tetterby and his Young Family. Significantly, Dickens has identified the young father with the publishing trade, although the hapless newsvendor merely has to market and not actually generate printed matter; undoubtedly, Dickens well have seen Tetterby as an extension of himself, surrounded by numerous progeny and unable to find a moment's peace, even in such extended vacation homes outside England to which he moved during the 1840s. The novelist, the second of seven siblings, lost a brother and a sister in childhood, and might well as a child have been made the "baby-minder" for Letitia, four years his junior, and even Harriet, born in 1819. The family life of the Tetterbys may reflect that of John and Elizabeth Dickens in Camden Town, London, in the early 1820s, prior to John's incarceration in the Marshalsea Prison for debt in 1824.

Illustrations for the Other Volumes of the Pears' Centenary Christmas Books of Charles Dickens (1912)

Each contains about thirty illustrations from original drawings by Charles Green, R. I. — Clement Shorter [1912]

- A Christmas Carol (28 plates) Vol. I (1892)

- The Chimes (31 plates) Vol. II (1894)

- L. Rossi's The Cricket on the Hearth (22 plates) Vol. III (1912)

- The Haunted Man (31 plates) Vol. V (1895)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Brereton, D. N. "Introduction." Charles Dickens's Christmas Books. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators Columbus: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man; or, The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

_____. The Haunted Man. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1848). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. II, 235-362, and 365-366.

_____. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas Time. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. (1895). London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. The Haunted Man. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley. The Household Edition. New York: James G. Gregory, 1861. II, 155-300.

Created 6 July 2015

Last modified 2 April 2020