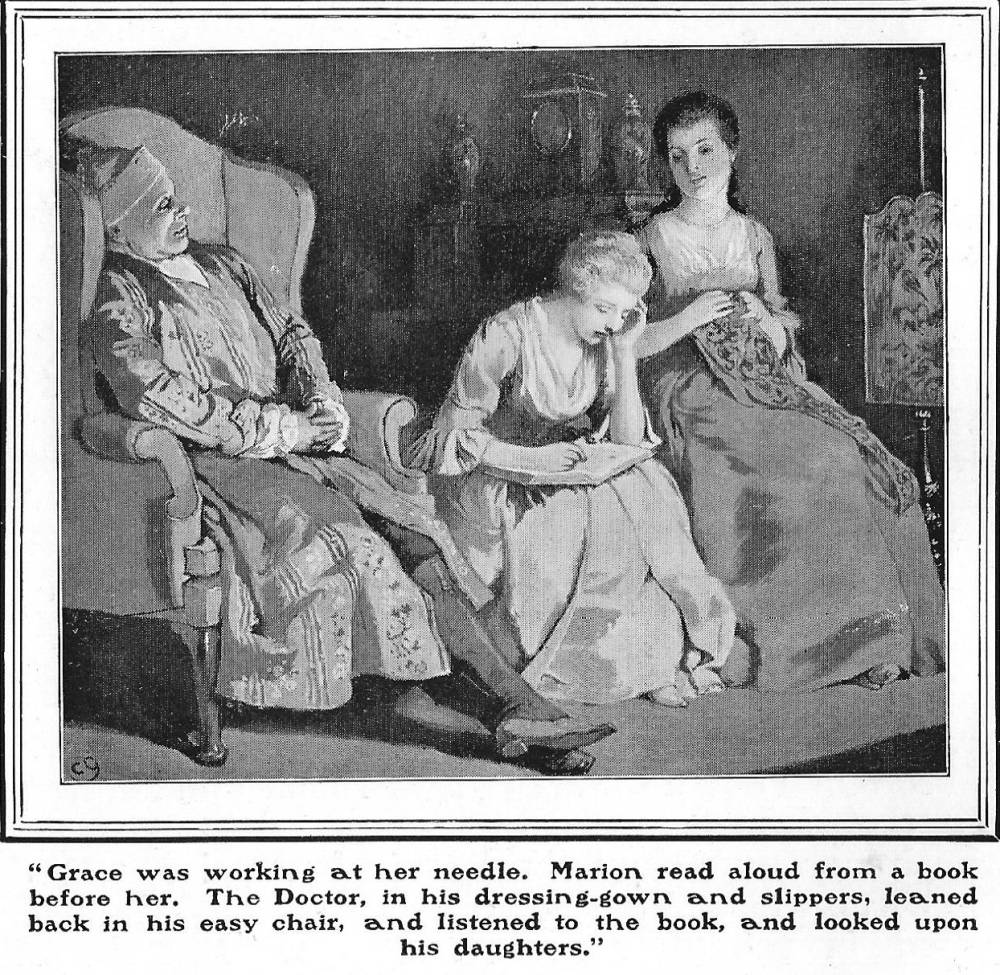

By the Fireside in Dr. Jeddler's Study by Charles Green (68). 1912. 7.5 x 9.3 cm, exclusive of frame. Dickens's The Battle of Life, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the lithographs often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (13-14). Specifically, By the Fireside in Dr. Jeddler's Study has a longer caption, the textual quotation "Grace was working at her needle. Marion read aloud from a book before her. The Doctor, in his dressing-gown and slippers, leaned back in his easy chair, and listened to the book, and looked upon his daughters" ("Part the Second," p. 67, from the text on the previous page) — a passage which establishes an analeptic reading for the illustration, since the text has already described the "cheerful fireside" (67) scene three years after Alfred's departure for medical studies abroad. Green has applied historical authenticity to the kind of realia appropriate to the realisation, with clothing, hairstyles, and even a tapestry fire-screen of the period of the latter part of the eighteenth century. Interestingly, Green's Dr. Jeddler is quite comfortable with the notion of sharing the masculine inner sanctum, his study, with his adolescent daughters, rendering it an extension of the family drawing-room. Given that the original and Household Edition volumes of 1876 and 1878 have no equivalent illustration, and that the Harry Furniss illustrations for the Christmas Books anthology in the Charles Dickens Library edition (1910) have nothing approximating this scene, one must ponder why Green, the last Victorian illustrator of the novella, elected to realize what appears to be a static scene of little importance to the narrative — other than that it establishes the tranquil tenor of the Jeddlers' lives in Alfred's absence.

Context of the Illustration

My story passes to a quiet little study, where, on that same night, the sisters and the hale old Doctor sat by a cheerful fireside. Grace was working at her needle. Marion read aloud from a book before her. The Doctor, in his dressing-gown and slippers, with his feet spread out upon the warm rug, leaned back in his easy-chair, and listened to the book, and looked upon his daughters.

They were very beautiful to look upon. Two better faces for a fireside, never made a fireside bright and sacred. Something of the difference between them had been softened down in three years' time; and enthroned upon the clear brow of the younger sister, looking through her eyes, and thrilling in her voice, was the same earnest nature that her own motherless youth had ripened in the elder sister long ago. But she still appeared at once the lovelier and weaker of the two; still seemed to rest her head upon her sister's breast, and put her trust in her, and look into her eyes for counsel and reliance. Those loving eyes, so calm, serene, and cheerful, as of old. ["Part the Second," 67]

Commentary

In this half-page lithograph, Green suggests the differences in their tastes and temperaments. Although the pair are devoted to each other and their father, their love for Alfred has cast a shadow over their relationship. Grace, doing her needlework (a piece embroidery looking like abell-pull or a curtain tie-back), is better suited to be the wife of a country general practitioner; Marion, whose literary tastes run to the sentimental, is nevertheless more active, more vivacious, and better suited to the greater world beyond the timeless English village where Alfred Heathfield will practice medicine and raise a family. To Dickens and other mid-Victorians, home and hearth possessed an almost sacred status, and a supportive family was a blessing conferred upon the virtuous. Hence, the quasi-biblical language in which Dickens couches the text from which Marion reads possesses religious overtones and apostrophizes the concept of home as an aspect of a benevolent deity: "O Home, so true to us, so often slighted in return, be lenient to them that turn away from thee, and do not haunt their erring footsteps too reproachfully!" [emphasis added to underscore the scriptural rhetoric of the passage that Marion reads, supposedly from a sentimental novel]. That the language borrows from Christian scripture and devotional commentary may have actually be a deterrent to illustration. Green illuminates the faces of all three figures and the doctor's substantial easy-chair with the glow of the unseen blaze in the grate, throwing into the shadows the clock and the vases in the background.

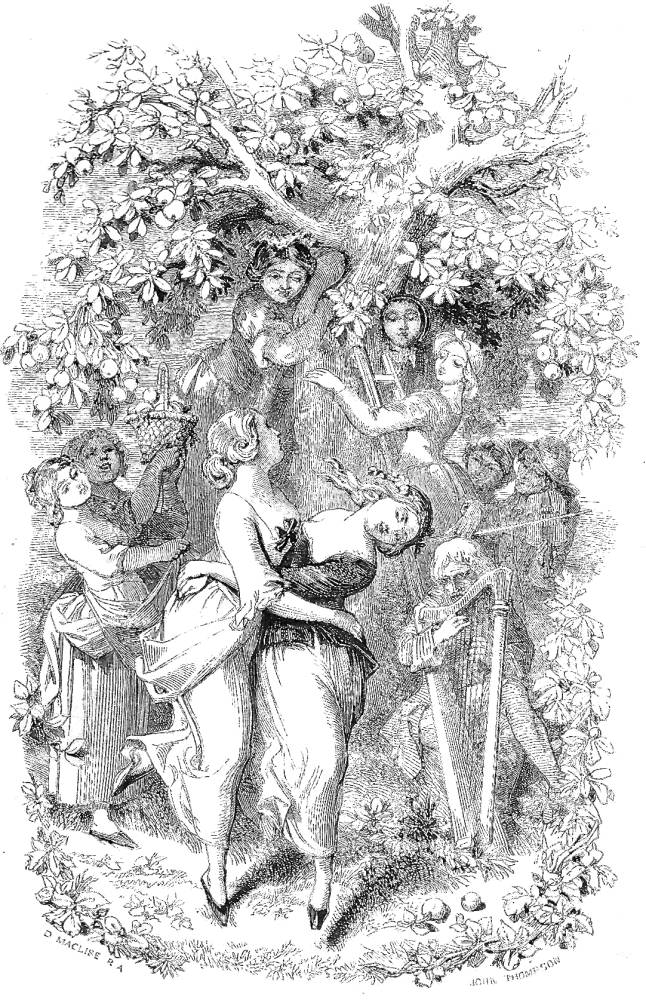

The scene of Marion's emotional reading about the comforts of home prepares the reader for Marion's abandoning her father and sister at the Christmas party in order to make way for Grace as Alfred's wife, so that Dickens is at pains in the accompanying text to reveal Marion's inner conflict as the text that the author has contrived for Marion to read aloud speaks of the anguish of the deserter of hearth and home that Marion contemplates that she herself must become to effect her sister's happiness. In Green's picture, neither the attractive Grace nor the dozing Dr. Jeddler in embroidered silk dressing-gown and nightcap apprehends the cause of Marion's breakdown, of course, contributing to the irony of the scene. Unfortunately, the sisters' beauty pales in comparison to that of the young women decorously dancing in the 1846 keynote illustration, Royal Academician Daniel Macliser's Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing (see below), the frontispiece for the original 1846 volume. Here, then, Green's photographic realism, detailed though it is with respect to objects lending credibility to the picture, works less well than Harry Furniss's impressionistic interpretation of the youthful beauties in Alfred's Farewell (see below). Green's realistic interpretation of the Jeddler family lacks the charm and verve of Barnard's "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday" (see below).

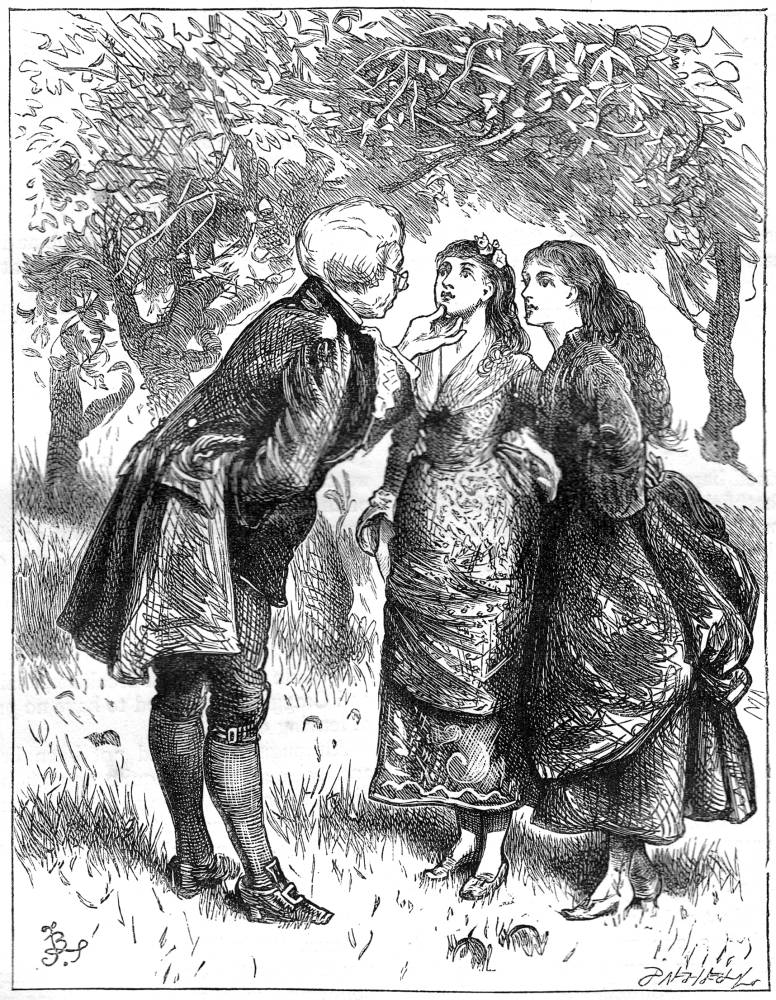

In the Household Edition of 1878 Fred Barnard, having a very limited program of illustration with which to work, does not include a scene involving the Jeddlers in the years that Alfred is absent, but does depict the sisters and their father in the orchard on Marion's birthday — the day of Alfred's departure — in "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday" (see below), in which at least physically the artist distinguishes the older, brunette Grace from the younger, blonde Marion. Otherwise, at least to Barnard, they are very similar types, both in fashion and their abundant, Pre-Raphaelite hair.

Relevant Illustrations from other Editions, 1846-1910

Left: Maclise's "fine arts" interpretation of the orchard dance in Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing. Centre: Barnard's more genial realisation of the family, "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday." (1878). Right: Furniss's description of the Jeddler sisters, Alfred's Farewell (1810).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

___. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1846). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

___. The Battle of Life. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

___. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

___. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

___. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

___. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

___. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 22 May 2015

Last modified 19 March 2020