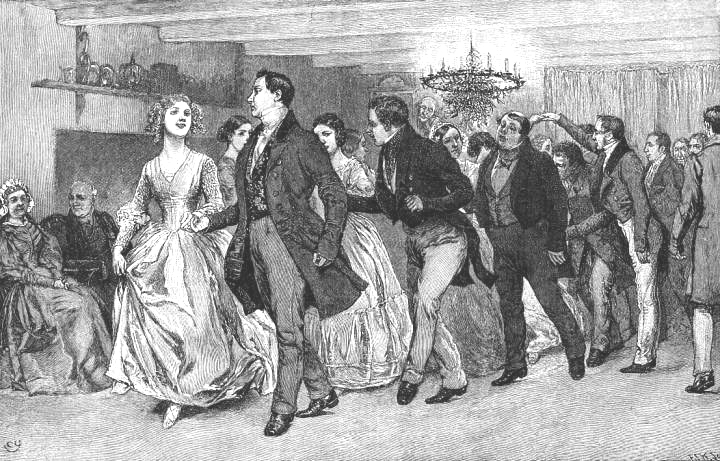

Among Those Who Danced Most Continually Were the Two Engaged Couples by Charles Green — an illustration for Thomas Hardy's "The History of the Hardcomes" in "Wessex Folk." Harper's New Monthly Magazine (March 1891): 594. Lithograph, 12 cm high by 18.8 cm wide.

Context of the Illustration

Among those who danced most continually were the two engaged couples, as was natural to their situation. Each pair was very well matched, and very unlike the other. James Hardcome’s intended was called Emily Darth, and both she and James were gentle, nice-minded, in-door people, fond of a quiet life. Steve and his chosen, named Olive Pawle, were different; they were of a more bustling nature, fond of racketing about and seeing what was going on in the world. The two couples had arranged to get married on the same day, and that not long thence; Tony’s wedding being a sort of stimulant, as is often the case; I’ve noticed it professionally many times.

They danced with such a will as only young people in that stage of courtship can dance; and it happened that as the evening wore on James had for his partner Stephen’s plighted one, Olive, at the same time that Stephen was dancing with James’s Emily. It was noticed that in spite o’ the exchange the young men seemed to enjoy the dance no less than before. By and by they were treading another tune in the same changed order as we had noticed earlier, and though at first each one had held the other’s mistress strictly at half-arm’s length, lest there should be shown any objection to too close quarters by the lady’s proper man, as time passed there was a little more closeness between ’em; and presently a little more closeness still.

The later it got the more did each of the two cousins dance with the wrong young girl, and the tighter did he hold her to his side as he whirled her round; and, what was very remarkable, neither seemed to mind what the other was doing. [Life's Little Ironies, Osgood, McIlvaine edition, "The History of the Hardcomes," 238-39]

Commentary: Changing Partners in The Dance of Life

Whereas the series' opening story, "Tony Kytes, the Arch-Deceiver," encapsulates the comedic, "battle of the sexes" aspect of courtship and marriage, Hardy's second ironic story presents a sharp contrast. Here, we move from the romantic pastoral of Shakespeare to a fatalistic tale of star-crossed lovers: what was "planned by nature" is undone in an impetuous moment by the cousins in "The History of the Hardcomes," the second oral tale of A Few Crusted Characters.

In Among Those Who Danced Most Continually, the second illustration of the March 1891 magazine instalment, the illustrator focuses upon the joyous celebration of old Christmas at Tony Kytes's "wedding-randy." The community celebrates young carrier's marriage in the time-honoured Wessex manner, with a fiddler (upper centre) providing a lively tune for the country-dance. Even though the styles worn by the young couples in the lithograph are of the metropolis, their values and usages turn out to be highly traditional. Again, Hardy distinguishes between what makes a thrilling romance, the electrical attraction of opposites, and what constitutes the basis for an effective marriage, the partnership of those with complementary tastes, perceptions, and aspirations. Caught up in the excitement of the dance, Steve and James Hardcome, first-cousins, unwisely exchange sweethearts and marry women ill-suited to their dispositions. The story that begins with a rollicking community party ends with the drowning of the one Hardcome and his cousin's wife, reunited in death. Hardy contrasts this melancholy outcome with what Kristin Brady terms the "lively sexual atmosphere of the country dance [which] leads to an impulsive changing of partners" (144) not merely for the evening's dance, so positively conveyed in the yuletide chandelier and fashionably accoutred partners, but for the dance of life.

Of the plate's twenty figures, males predominate, since the power of choice — for dance-partners and for life-companions — is in their hands. The female figures are largely eclipsed. A seated elderly couple reduced to the status of mere spectators and commentators for both types of dance, contrasts the active courtship of the central figures, whom the artist has dressed in Regency attire to imply a chronological setting some sixty years earlier. Green has captured well the unemotional nature of the first male dancer and the lively charm and coiled blonde curls of his partner, the more outgoing Olive; the second couple reverse these dispositions, the young woman (presumably, Emily, again in bridal white) looking disagreeably at her fianc&eacut; James ahead of her. Already, then, the viewer is being prepared by the headnote illustration for the disruption in the dual courtship enacted prior to the dance.

The first two stories in Wessex Folk, that of Tony Kytes (not illustrated, except that the dance of the illustration is the social culmination of the young carrier's courtship) and that of the Hardcomes, are the keynote for the entire sequence: whereas the first focuses on the fickleness of the protagonis’s marital choice, the second carries us beyond the courtship stage to two of life's other main events, marriage and death. Like Tony, as Brady notes, in changing life-partners after the dance and in attempting to undo that reversal after marriage, "Stephen Hardcome and his cousin's wife drift into an irrational state of sexual oblivion, carried by the tide of emotion into a forgetfulness of all their previous commitments and responsibilities" (145).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Brady, Kristin. The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy: Tales of Past and Present. London & Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1984.

Hardy, Thomas. "The History of the Hardcomes." [March 1891] Life's Little Ironies: A Set of Tales with Some Colloquial Sketches Entitled "A Few Crusted Characters." London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1894. 237-49.

Hardy Thomas. Wessex Folk (subsequently renamed A Few Crusted Characters) in Harper's New Monthly Magazine 81 (March-May 1891): 594, 701, 703, 891, 894; 82 (June 1891): 123.

Ray, Martin. Chapter 25, "A Few Crusted Characters." Thomas Hardy: A Textual Study of the Short Stories. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997. 228-258.

Created 13 June 2008

Last modified 17 April 2020