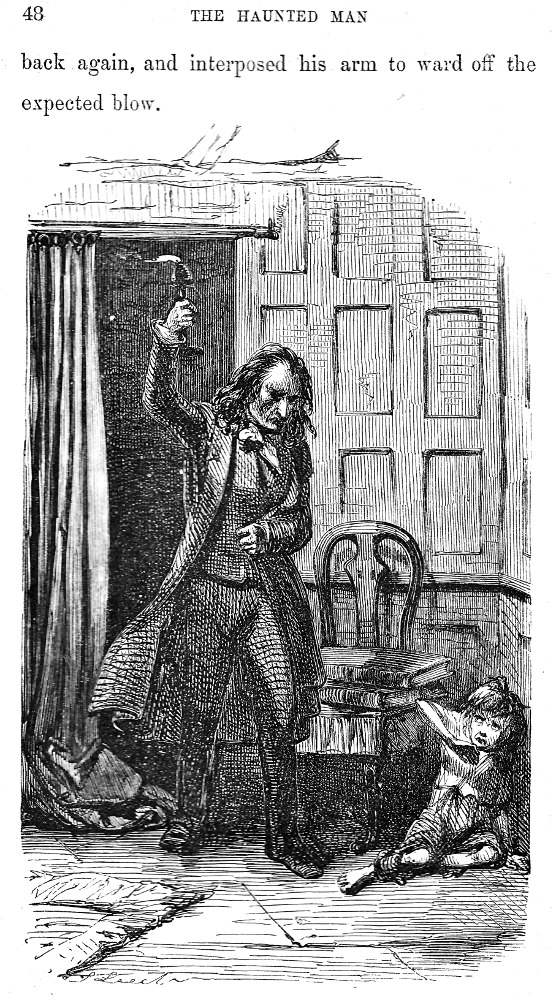

Redlaw and the Boy

John Leech; engravers, Smith & Cheltnam.

1848

12.4 cm by 7.5 cm (4 ¾ by 3 inches), framed.

Seventh illustration for Dickens's The Haunted Man, "Chapter I, The Gift Bestowed," page 48.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Little of Leech's usual sense of comedy and caricature appears in his second plate. However, he allows a strongly felt emotion to dominate. The pathos of the protagonist's confrontation with a personification of poverty and ignorance recalls Leech's 1843 wood-engraving Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol. [Commentary continues below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.