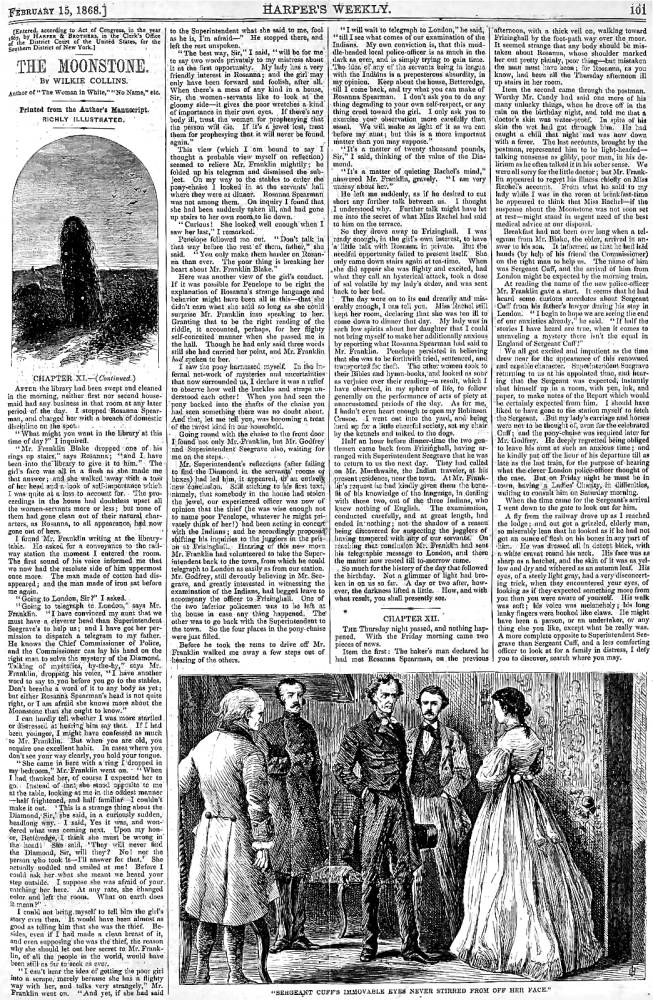

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder." Chapter 11, Continued — initial illustration for the seventh instalment in Harper's Weekly (15 February 1868), p. 101, p. 55 in volume. Wood-engraving, 8.5 x 5.4 cm. (3 ⅜ by 2 ⅛ inches). [The seventh headnote vignette presents Rosanna Spearman crossing the moor, probably on her way to the Shivering Sand and the village of Cobb's Hole, where her only real friend, Limping Lucy, a fisherman's daughter, lives.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Seventh Instalment

The Thursday night passed, and nothing happened. With the Friday morning came two pieces of news.

Item the first: the baker's man declared he had met Rosanna Spearman, on the previous afternoon, with a thick veil on, walking towards Frizinghall by the foot-path way over the moor. It seemed strange that anybody should be mistaken about Rosanna, whose shoulder marked her out pretty plainly, poor thing — but mistaken the man must have been; for Rosanna, as you know, had been all the Thursday afternoon ill up-stairs in her room. — "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," Chapter 12, p. 101; p. 55 in volume.

Commentary

In a thick veil, walking across a moor, a wild space emblematic of the maid-servant's being a social outcast, the enigmatic figure must be that of Rosanna Spearman, who was supposedly ill and in her room that afternoon, but in fact was making her way to Cobb's Hole, the local fishing village. The headnote vignette implies this detail is important, and therefore misleads the reader into suspecting that the lonely, socially isolated reformed criminal is somehow involved in the theft. At this stage in the novel's American serialisation it is doubtful that either the illustrators or the readers of Harper's weekly realised that this illustration was something of a "red heering" or that Rosanna's behaviour was connected to the paint smears on the door of Rachel Verinder's sitting-room.

The girl's attempt at anonymity and the very position of the illustration suggest that Rosanna's behaviour bears some relation to the theft of the Moonstone, implying, perhaps, that she was making contact with her confederates in the crime, or that she was carrying the diamond to a safe hiding place, assumptions which are demonstrated by later events to be without substance. Rather, her attempting to hide the paint-stained nightgown is directly related to her infatuation with Franklin Blake, so that, like Rachel Verinder in the next illustration, "Sergeant Cuff's immovable eyes never stirred from off her face", she is merely trying to protect the handsome youth from the criminal investigation which Sergeant Cuff is about to launch. Like Dickens's Hard Times for These Times (1854), then, Collins in The Moonstone: A romance pits the (masculine) wisdom of the head against the (feminine) wisdom of the heart, as both women intuit that it is inconsistent with Blake's character to have committed the crime, even though seemingly incontrovertible evidence (Rachel's seeing him take the gem, and Rosanna's finding the paint-smeared nightgown the morning after the theft) implicates him.

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." P. 279.

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-529.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. With 66 illustrations. Vol. 12 (1 January-8 August 1868), pp. 5-503.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Gregory, E. R. "Murder in Fact." The New Republic. 22 July 1878, pp. 33-34.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Lonoff, Sue. Chapter 7, "The Moonstone and Its Audience." Wilkie Collins and His Readers: A Study of the Rhetoric of Authorship. New York: AMS Press, 1982. Pp. 170-230.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-19.

Created 26 November 2016

Last updated 1 November 2025