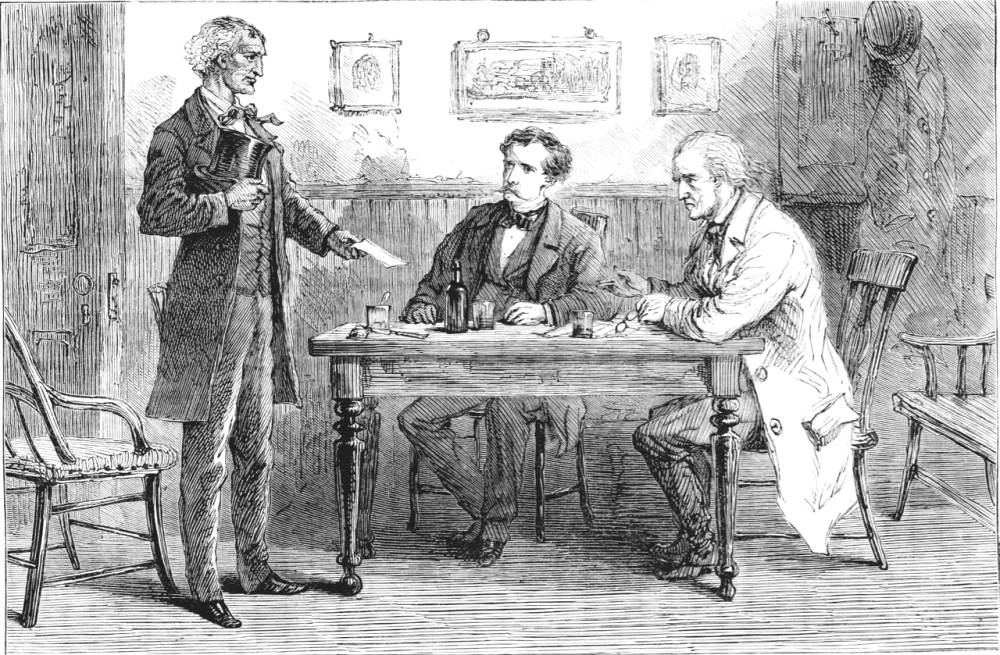

"He took a slip of paper from his pocket, and handed it to Betteredge." — second illustration for the twenty-third instalment of Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance. A wood-engraving by Harper & Bros. house illustrator "C. G. B." 11.5 cm high by 17.6 cm wide. 6 June 1868 instalment in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Chapter 4 in "Second Period. The Discovery of the Truth. 1848-1849.) Third Narrative. Contributed by Franklin Blake," p. 357. [Here, just as Franklin Blake despairs of solving the mystery of the nightgown since Sergeant Cuff has retired to raise roses in Dorking, there arrives upon the scene, as if sent by Providence, the outlandish figure of Dr. Candy's medical assistant, a physician in his own right, a middle-aged man of mixed race named Ezra Jennings.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Passage Illustrated: Betteredge introduces Blake to the local Anglo-Indian Doctor

"Then, Betteredge — as far as I can see now — I am at the end of my resources. After Mr. Bruff and the Sergeant, I don't know of a living creature who can be of the slightest use to me."

As the words passed my lips, some person outside knocked at the door of the room.

Betteredge looked surprised as well as annoyed by the interruption.

"Come in," he called out, irritably, "whoever you are!"

The door opened, and there entered to us, quietly, the most remarkable-looking man that I had ever seen. Judging him by his figure and his movements, he was still young. Judging him by his face, and comparing him with Betteredge, he looked the elder of the two. His complexion was of a gipsy darkness; his fleshless cheeks had fallen into deep hollows, over which the bone projected like a pent-house. His nose presented the fine shape and modelling so often found among the ancient people of the East, so seldom visible among the newer races of the West. His forehead rose high and straight from the brow. His marks and wrinkles were innumerable. From this strange face, eyes, stranger still, of the softest brown — eyes dreamy and mournful, and deeply sunk in their orbits — looked out at you, and (in my case, at least) took your attention captive at their will. Add to this a quantity of thick closely-curling hair, which, by some freak of Nature, had lost its colour in the most startlingly partial and capricious manner. Over the top of his head it was still of the deep black which was its natural colour. Round the sides of his head — without the slightest gradation of grey to break the force of the extraordinary contrast — it had turned completely white. The line between the two colours preserved no sort of regularity. At one place, the white hair ran up into the black; at another, the black hair ran down into the white. I looked at the man with a curiosity which, I am ashamed to say, I found it quite impossible to control. His soft brown eyes looked back at me gently; and he met my involuntary rudeness in staring at him, with an apology which I was conscious that I had not deserved.

"I beg your pardon," he said. "I had no idea that Mr. Betteredge was engaged." He took a slip of paper from his pocket, and handed it to Betteredge. "The list for next week," he said. His eyes just rested on me again — and he left the room as quietly as he had entered it.

"Who is that?" I asked.

"Mr. Candy's assistant," said Betteredge. "By-the-bye, Mr. Franklin, you will be sorry to hear that the little doctor has never recovered that illness he caught, going home from the birthday dinner. He's pretty well in health; but he lost his memory in the fever, and he has never recovered more than the wreck of it since. The work all falls on his assistant. Not much of it now, except among the poor. They can't help themselves, you know. They must put up with the man with the piebald hair, and the gipsy complexion — or they would get no doctoring at all."

"You don't seem to like him, Betteredge?"

"Nobody likes him, sir."

"Why is he so unpopular?"

"Well, Mr. Franklin, his appearance is against him, to begin with. And then there's a story that Mr. Candy took him with a very doubtful character. Nobody knows who he is — and he hasn't a friend in the place. How can you expect one to like him, after that?" — "Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) Third Narrative. Contributed by Franklin Blake," Ch. IV, p. 358.

Commentary

The phrase "the most remarkable-looking man that I had ever seen" has already been applied by Mr. Bruff's clerk to the leader of the Brahmins, an East Indian dressed in the Western manner; here, the phrase seems to denote Ezra Jennings' mixed-race background, which has given him a distinctive appearance that people in Yorkshire apparently find repellent. Thus, Collins employs Ezra Jennings to reveal Betteredge's racism — his misogynous attitude having been established much earlier, although one senses that these conventional prejudices are not so much a matter of intolerance as ignorance in Betteredge, who has already undermined his sexism by praising his daughter Penelope and acting protectively towards Rosanna Spearman. Ironically, it will be Ezra Jennings who provides Franklin Blake with a solution to his personal mystery.

Perhaps the most carefully constructed of these sympathetic outsiders — Sue Lonoff cals him "the book's most extraordinary character" [202] — is Ezra Jennings, the misunderstood assistant to the Verinders' physician, Dr. Candy. Some have seen in Jennings clear touches of autobiography, and indeed, the delicacy of the portrait suggests a special feeling on the part of its creator. As with Rosanna and Limping Lucy, Collins gave Ezra Jennings a number of physical irregularities — a dark, gipsy complexion, fleshless and sunken cheeks, freakish parti-coloured hair — that help set him apart from the conventional. He is defined, as well, by a dark past, a notably Collinsian addiction to laudanum, and an inability to escape the hounding persecution of the establishment. He is, alongside Rosanna and Lucy, a fellow sufferer and outcast. Ultimately, Franklin Blake, and through him Collins's audience, is compelled to admit that "it is not to be denied that Ezra Jennings made some inscrutable appeal to my sympathies, which I found it impossible to resist." — Farmer, 22.

Thus, the task of the illustrator is formidable because he must make Jennings look both odd (with East Indian features, perhaps) and intelligent, aloof (on account of the racism he has experienced) and sympathetic. As he interrupts the consumption of grog to present his piece of paper to Betteredge, the estate steward and Blake seem to be studying him, but there is no suggestion of dislike in Betteredge's expression. For all the outlandish qualities that Collins describes the illustrator has managed the piebald hair and a benign expression — his features do not in the least seem Asiatic, however.

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite The Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-503.

________. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Farmer, Steve. "Introduction" to Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 1999. Pp. 8-34.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serialization.pdf

Lonoff, Sue. Chapter 7, "The Moonstone and Its Audience." Wilkie Collins and His Readers: A Study of the Rhetoric of Authorship. New York: AMS Press, 1982. Pp. 170-230.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "Introduction" to Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone." Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1966. Pp. 7-24.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 16 September 2016

Last modified 7 November 2025