Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–96) was one of the most important and influential painters of his time. One time President of The Royal Academy and knighted the day before his death in 1896, Leighton was a model academician whose classical paintings dominated the taste of the mid and late nineteenth century. An accomplished draughtsman, he was also a colourist of poetic intensity. In pictures such as The Garden of the Hesperides (1892, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight), he created a version of the ancient past in which the emphasis is on mood and ambience rather than narrative. A major voice in the development of Aesthetic neo-classicism, his pictures are hermetic, interior worlds, visions of an idealized heroism; charged with sexual ambivalence, his paintings reflect on endeavour and loss.

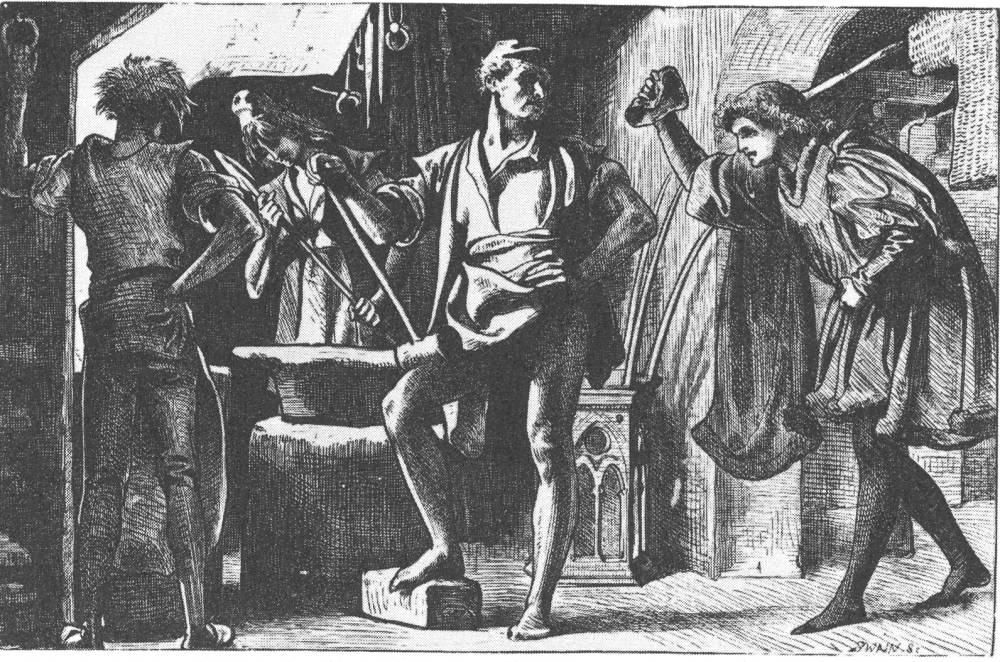

Left to right: (a) Tessa at Home. (b) Niccolò at Work. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Although a colourist on an epic scale, Leighton also made a small but significant contribution to the development of mid-Victorian illustration. Working as an artist in black and white whose images were engraved on wood by Linton and Swain, he produced distinguished designs for George Eliot’s Romola, which first appeared in The Cornhill Magazine in 1862–63. George Smith of the publishers Smith, Elder, engaged Leighton as Eliot’s partner for two reasons: partly to project The Cornhill as a magazine that contained the best art-work, an essential move in a market dominated by keen competition with its illustrated rivals, Good Words and Once a Week; and partly because Leighton (whose early paintings had focused on Florentine or at least Italianate scenes) was a natural choice as the interpreter of Eliot’s tale.

Smith secured Leighton’s interest by paying him the indulgent sum of £480. This was far in excess of the going rate of £10 – £15 per ‘cut’, giving him £20 per illustration in a series of 23 full-page designs, although Leighton also produced initial letters as part of his contract. For Eliot, on the other hand, Smith was even more excessive, paying her the outrageous fee of £2,000 in a period when £500 was generous. Smith seemed to have reckoned that his capital would produce profitable results in the form of increased sales; in the event, the novel was a failure, never recouped its costs, and is today the least read of Eliot’s texts. Its enduring interest lies more in the quality of Leighton’s designs, which stand out as a prime example of painting at the service of graphic design. The dual-text’s production was nevertheless a vexed one. What Smith did not anticipate was the complicated nature of the collaboration between Eliot and Leighton, and the manifold difficulties generated by working with an artist of Leighton’s status and character.

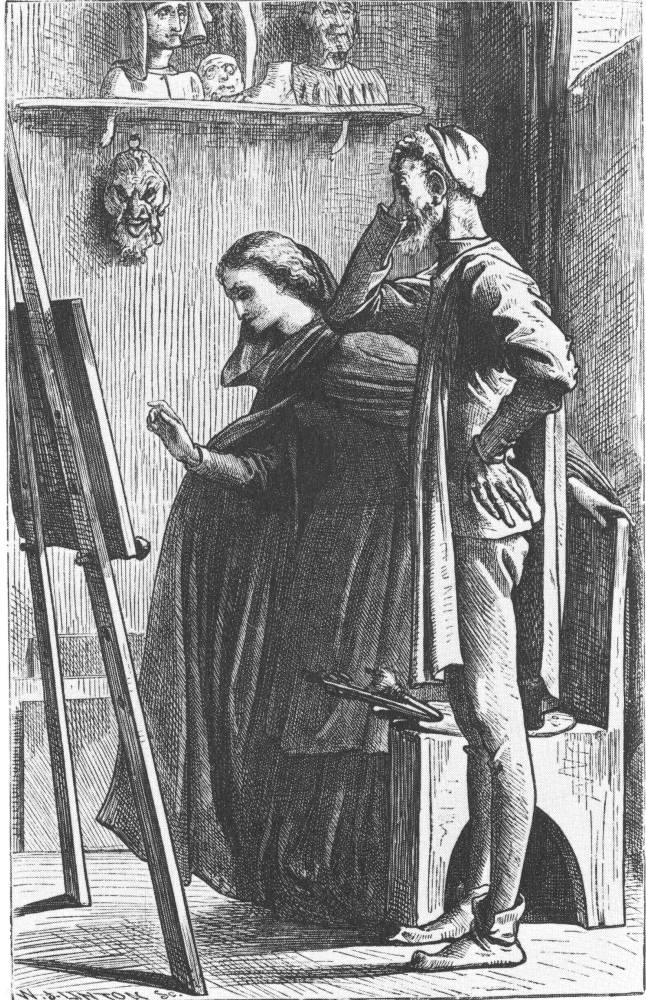

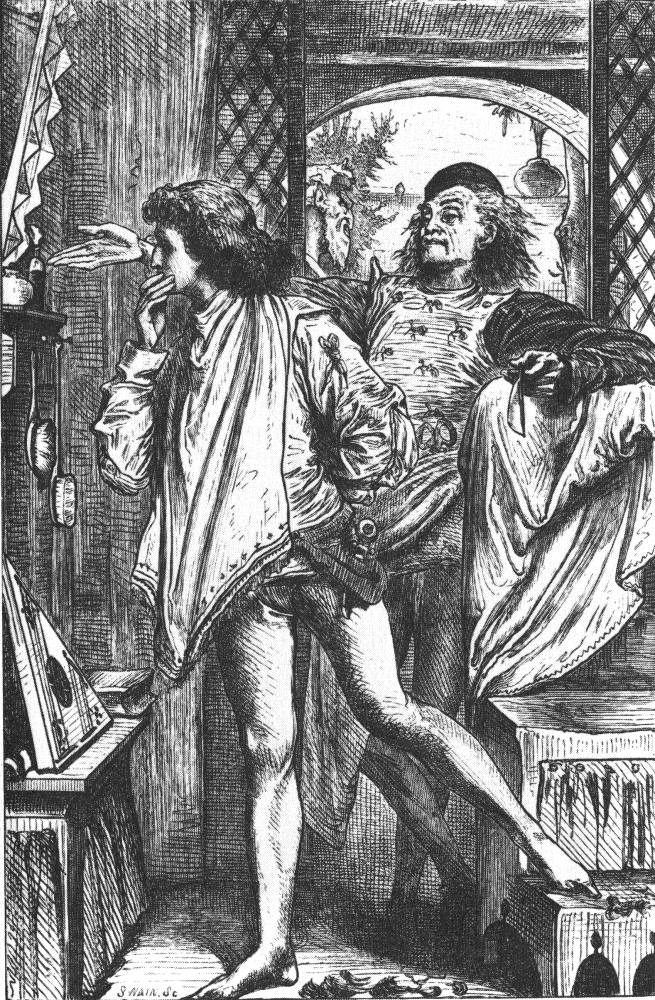

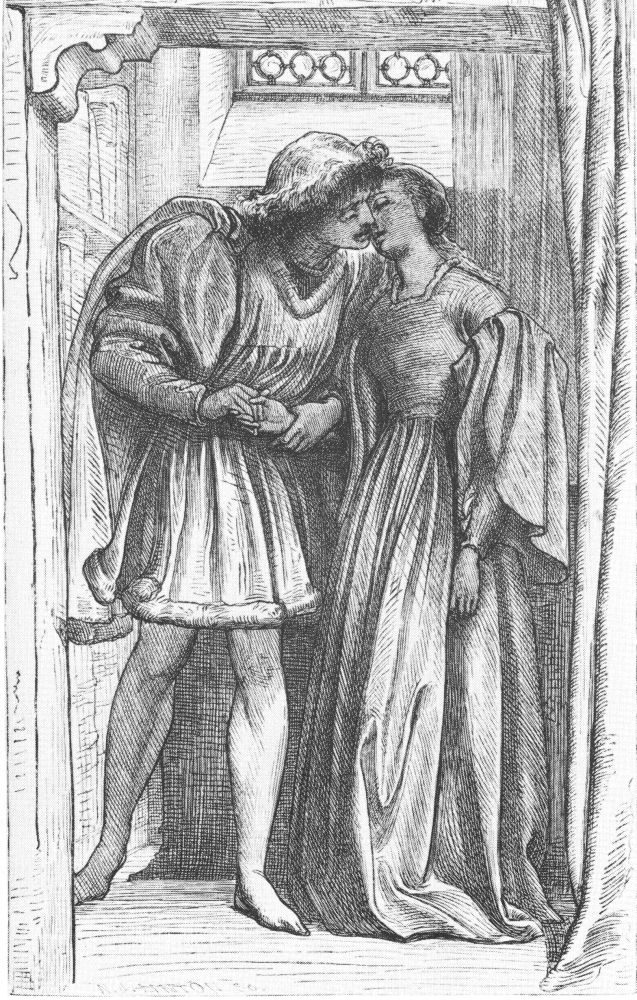

Left to right: (a) The Blind Scholar and His Daughter. (b) The Painted Record. (c) Suppose You Let Me Look at Myself. (d) The First Kiss. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

These problems were primarily the result of Leighton’s non-compliance with the role of illustrator, as narrowly defined. Though artists such as Rossetti had asserted the illustrator’s right to impose his own interpretation on the written material, there was still a general expectation that designers should take direction from the author, focus on the material the writer highlighted, and provide a literal representation of the written text in a visual form. This arrangement was sometimes unworkable, and Leighton’s dealings with Eliot are characterized by his unwillingness to do anything other than present his own, highly idiosyncratic treatments of his source material. Uncooperative, difficult, difficult to please and outspoken, Leighton was professionally far removed from the version of compliance modelled by illustrators such as Phiz.

The turbulent relationship between Eliot and Leighton is enshrined in a series of letters directed from the author to ‘her’ artist. Her opening missives articulate her idea of the writer as the dominant force and director, telling Leighton what to illustrate and which elements he should focus on. Illustration, she says, should only be sort of ‘overture’ to the text. For Leighton, on the other hand, the written text was purely the preamble or stimulus to his own imaginative creations. There was no possible compromise and in practice Leighton disregards the author’s polite attempts at manipulation, accommodating her demands only when they matched his own artistic aims and only when he thought they could be realized in a visual form. Indeed, by the end of their working relationship the power had shifted firmly into Leighton’s hands. Eliot started off by telling him what to do, but she later accepts the artist’s advice, changing details in manuscript to accord with his idea of how the novel should be represented (Cooke, Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s, pp. 147–62.) The end-result is a dual-text of unusual complexity and richness, a visual-verbal product in which the meanings are negotiated and re-negotiated within the unstable interactions of image and word.

Leighton’s interpretation preserves some elements of Eliot’s text. The Renaissance settings and décor are presented with an antiquarian precision, and the illustrations give robust tangible form to the figure of Romola and the other main characters. But the artist also imposes – or constructs – his own readings. He foregrounds the text’s submerged sexuality in illustrations such as ‘The First Kiss’ (The Cornhill Magazine, September 1862, facing p.289), and he also explores the nature of time and change, a theme announced in the opening design of ‘The Blind Scholar and his Daughter’ (The Cornhill Magazine, July 1862, facing p.1). Stressing mutability rather than historical period, the passage of events rather than the time-bound parameters of the historical novel, Leighton deepens and expands the range of Eliot’s text: in part a reading which privileges the immediacy of the here and now, his illustrations also remind us of the enduring, ritualistic nature of all human experience. Eliot’s novel is about life in a particular period, while Leighton’s montage is a story of archetypes.

Works Cited

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Cornhill Magazine, The. London: Smith, Elder, 1862–63.

Last modified 14 November 2012