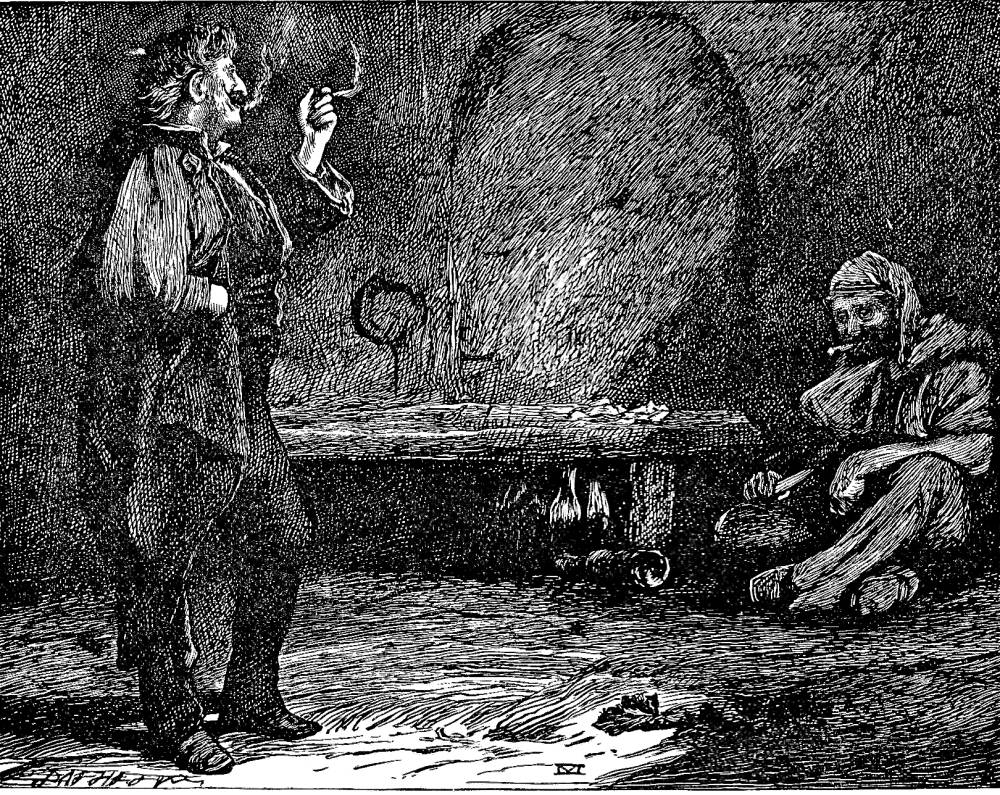

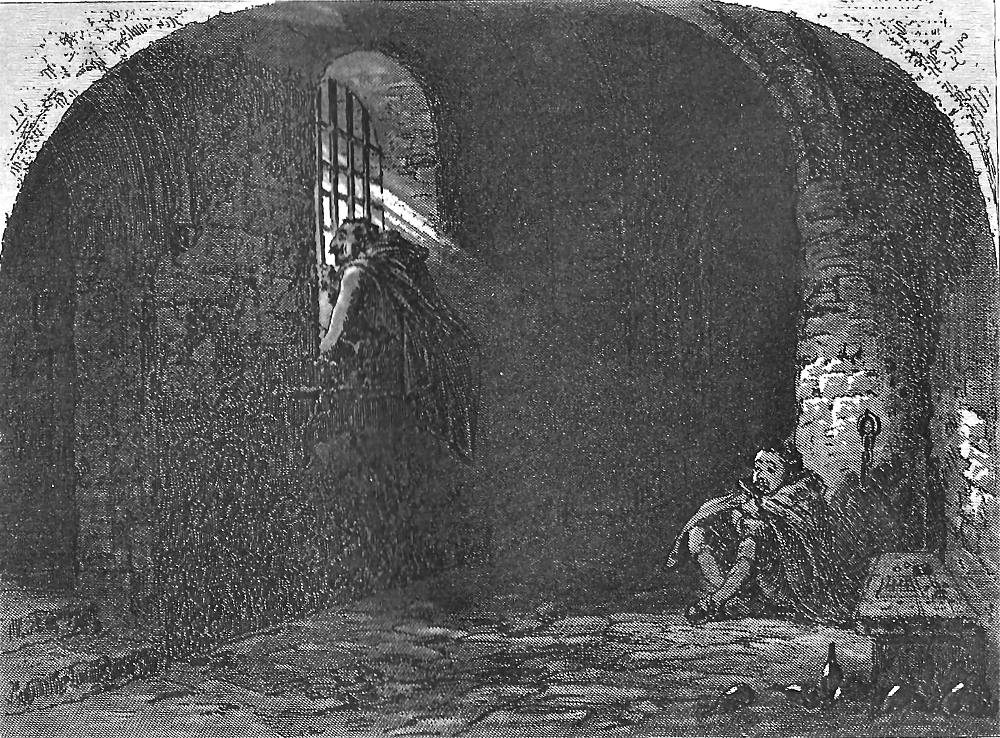

In Marseilles that day there was a villainous prison. In one of its chambers, so repulsive a place, that even the obtrusive stare blinked at it, and left it to such refuse of reflected light as it could find for itself, were two men. — Book I, chap. 1, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's third illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1875. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.4 cm high x 13.4 cm wide. The Chapman and Hall woodcut is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition. The scene, as in the original Hablot Knight Browne December 1855 illustration The Birds in the Cage, is a dank, poorly-lit prison cell in Marseilles about 1820 in the month of August, and the characters depicted in the Mahoney wood-engraving are Monsieur Rigaud, a wealthy Frenchman accused of murdering his wife, and John Baptist Cavalletto, a Genoese smuggler, for whom the turnkey and his daughter have radically different meals as Rigaud can afford to supplement the spartan prison diet with a number of luxuries. The illustration makes it clear that the novel begins inside a prison cell, the first of a number of such institutions and buildings in Little Dorrit, whose central symbol is the Marshalsea, the notorious debtors' prison in which the novelist's own father, John, was incarcerated in the 1820s, as James Mahoney, having read John Forster's The Life of Charles Dickens, would have known.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

The other man spat suddenly on the pavement, and gurgled in his throat.

Some lock below gurgled in its throat immediately afterwards, and then a door crashed. Slow steps began ascending the stairs; the prattle of a sweet little voice mingled with the noise they made; and the prison-keeper appeared carrying his daughter, three or four years old, and a basket.

"How goes the world this forenoon, gentlemen? My little one, you see, going round with me to have a peep at her father's birds. Fie, then! Look at the birds, my pretty, look at the birds."

He looked sharply at the birds himself, as he held the child up at the grate, especially at the little bird, whose activity he seemed to mistrust. "I have brought your bread, Signor John Baptist," said he (they all spoke in French, but the little man was an Italian); "and if I might recommend you not to game —"

"You don't recommend the master!" said John Baptist, showing his teeth as he smiled.

"Oh! but the master wins," returned the jailer, with a passing look of no particular liking at the other man, "and you lose. It's quite another thing. You get husky bread and sour drink by it; and he gets sausage of Lyons, veal in savoury jelly, white bread, strachino cheese, and good wine by it. Look at the birds, my pretty!"

"Poor birds!" said the child.

The fair little face, touched with divine compassion, as it peeped shrinkingly through the grate, was like an angel's in the prison. John Baptist rose and moved towards it, as if it had a good attraction for him. The other bird remained as before, except for an impatient glance at the basket.

"Stay!" said the jailer, putting his little daughter on the outer ledge of the grate, "she shall feed the birds. This big loaf is for Signor John Baptist. We must break it to get it through into the cage. So, there's a tame bird to kiss the little hand! This sausage in a vine leaf is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — this veal in savoury jelly is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again — these three white little loaves are for Monsieur Rigaud. Again, this cheese — again, this wine — again, this tobacco — all for Monsieur Rigaud. Lucky bird!" — Ch. 1, "Sun and Shadow."

Commentary

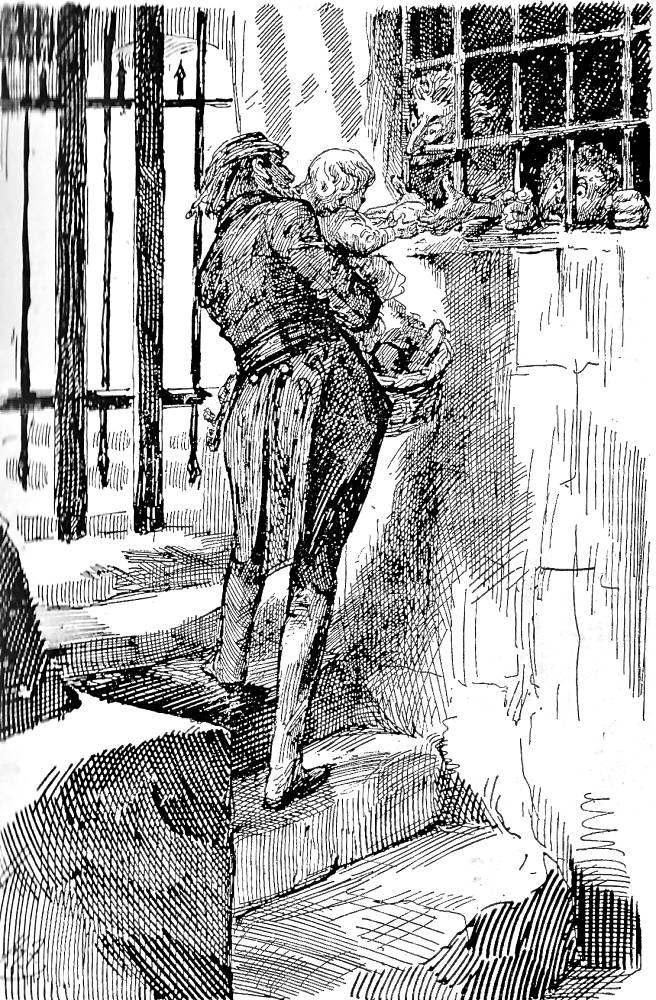

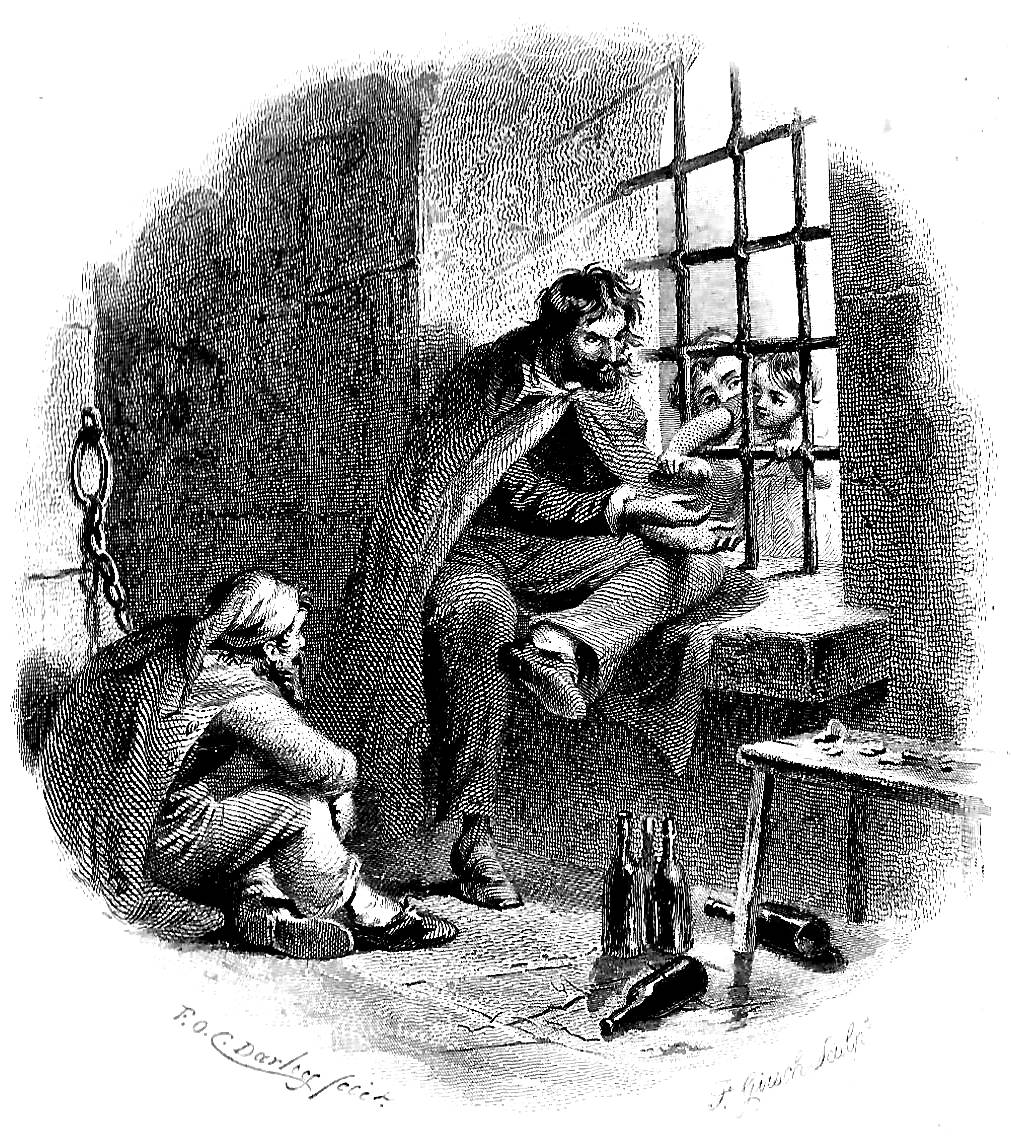

Although Hablot Knight Browne in the monthly parts, December 1855 through June 1857, has not provided with Mahoney a useful model for this scene, he does show Rigaud in Gowan's studio (Book Two, Chapter 6), Instinct Stronger than Training and with the Clenhams' crusty servant in Mr. Flintwich Receives the Embrace of Friendship (Book Two, Chapter 10), and both Rigaud and "Mr. Baptist" in In the Old Room (Book Two, Chapter 28). Not immediately evident in the cavernous darkness of Phiz's The Birds in the Cage (Book One, Chapter 1), the jailor and his young daughter, faces at the bars, are subordinated in Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece entitled Feeding the Birds to the villainous Rigaud, a gentlemanly murderer who later adopts the pseudonym Blandois, an associate of Mrs. Clenham and Henry Gowan. Albeit a secondary character, Blandois Rigaud in the Mahoney plate is a realistic version of the bearded, satanic foreigner, an "other" to the novel's smooth-faced Englishmen. There is more than a whiff of Brimstone about Rigaud Blandois in the Mahoney illustrations as he is depicted smoking in his initial appearance, bearded, self-confidant, perpetually smiling. A pool of light, presumably emanating from the cell's small window, contains Mahoney's initial and enables the artist to show a niche in the back wall, the straw on the floor, and Rigaud's resigned cellmate, the affable Genoese smuggler Giovanni Battista.

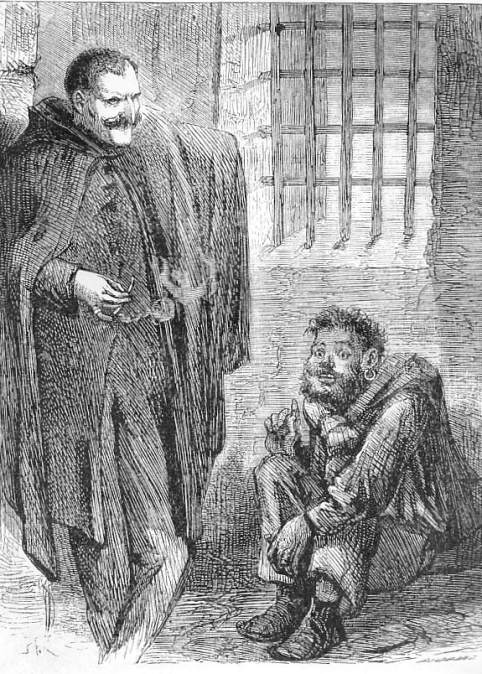

A rather different interpretation of the ill-sorted pair of prisoners occurs in the 1867 Diamond Edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. illustration Rigaud and Cavaletto (Chapter One, "Sun and Shadow"). Although Phiz's images of Rigaud are acceptable for establishing the novel's dominant tone, Darley's frontispiece captures more of Rigaud's robustness and deviousness, qualities which render him a foil to the good-hearted peasant, Cavaletto, who will become an associate of Arthur Clenham. The American editions of the 1860s appear not to have influenced such later British interpretations as James Mahoney's in the Household Edition, the full title for the wood-engraving being In Marseilles that day there was a villainous prison. In one of its chambers, so repulsive a place, that even the obtrusive stare blinked at it, and left it to such refuse of reflected light as it could find for itself, were two men. — Book I, chap. 1. Although Mahoney shows neither the window nor the turnkey and his daughter, this illustration seems to be directly derived from Phiz's original dark plate The Birds in the Cage — Book One, Chapter One (December 1855). Like Harry Furniss in his 1910 narrative-pictorial sequence for the novel, Felix Octavius Carr Darley floods the scene with light. Darley's technical triumph becomes apparent when one regards these parallel illustrations, for Darley's composition contains enough plausible illumination to show the prisoners, and also contains the figures with whom we enter the scene in the text, the jailor and his four-year-old daughter, an angelic visage juxtaposed against the satanic face of the gentlemanly murderer of his wife, Rigaud. In the Furniss composition, "Feeding the Birds": Rigaud and John Baptist Imprisoned at Marseilles, however, the illustrator the same scene from outside the prison bars, as if Rigaud and Giovanni Battista are animals in a cage, and the jailor and his daughter visitors at a zoo.

Rigaud and Cavaletto in various editions, 1855-1910

Left: Harry Furniss's lithograph of the Marseilles prisoners as caged beasts, Feeding the Birds . . . (1910). Centre: F. O. C. Darley's frontispiece for the first of four 1863 volumes, Feeding the Birds (Household Edition, New York). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the Marseilles prisoners as a dual portrait, Rigaud and Cavaletto (1867). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of the Marseilles prisoners, a dark plate communicating little other than atmosphere, The Birds in the Cage (December 1855). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1919. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 28 December 2015