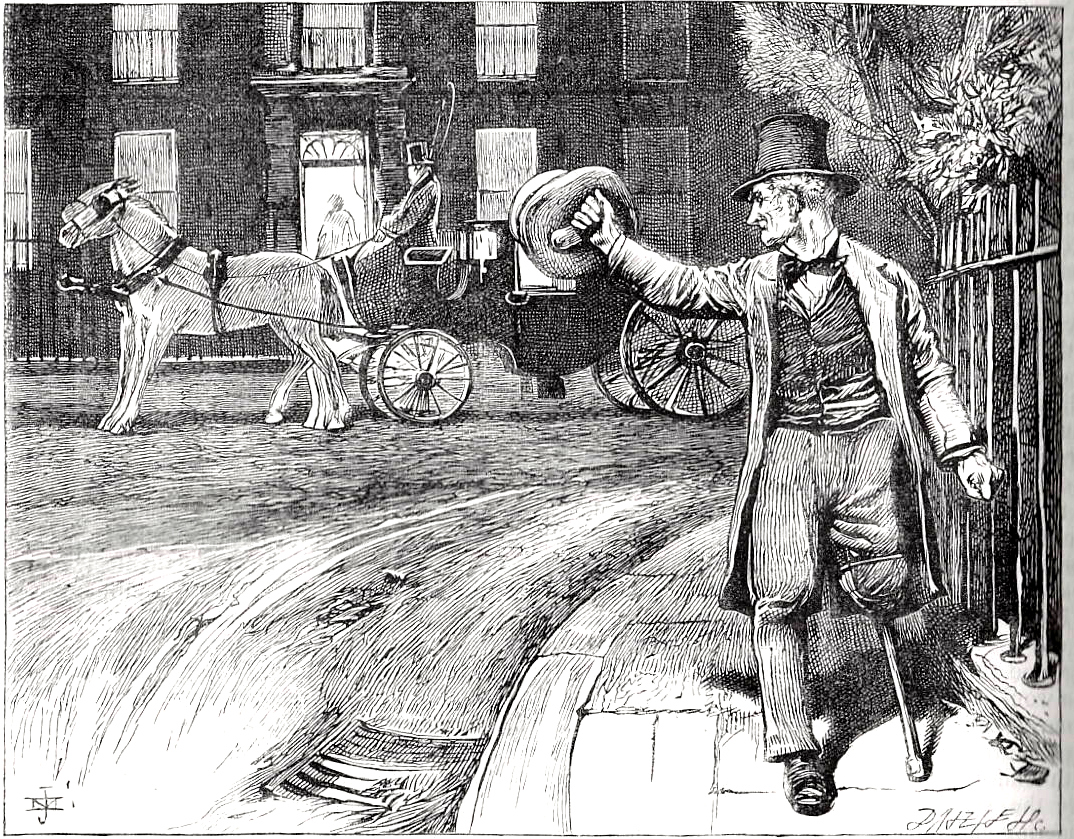

"There'll shortly be an end of you," said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. Your varnish is fading. (p. 214) — James Mahoney's thirty-seventh illustration for Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition (New York), 1875. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high x 13.3 cm wide. The Harper and Brothers woodcut for the third book's seventh chapter, "The Friendly Move Takes Up a Strong Position," concerns Venus and Wegg's plot to rob Boffin of most of the Harmon fortune by employing the will that Wegg previously discovered in a cashbox in the Mounds:

Regularly executed, regularly witnessed, very short. Inasmuch as he has never made friends, and has ever had a rebellious family, he, John Harmon, gives to Nicodemus Boffin the Little Mound, which is quite enough for him, and gives the whole rest and residue of his property to the Crown." [211]

The scene of the Mahoney illustration is the street outside the Boffin (Harmon) mansion. The hatbox that Wegg waves at Boffin's carriage has added significance, for it is his means of concealing the cashbox containing the will — "an old leathern hat-box, into which he had put the other box, for the better preservation of commonplace appearances, and for the disarming of suspicion" [211].

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

After Silas had left the shop, hat-box in hand, and had left Mr. Venus to lower himself to oblivion-point with the requisite weight of tea, it greatly preyed on his ingenuous mind that he had taken this artist into partnership at all. He bitterly felt that he had overreached himself in the beginning, by grasping at Mr. Venus's mere straws of hints, now shown to be worthless for his purpose. Casting about for ways and means of dissolving the connexion without loss of money, reproaching himself for having been betrayed into an avowal of his secret, and complimenting himself beyond measure on his purely accidental good luck, he beguiled the distance between Clerkenwell and the mansion of the Golden Dustman.

For, Silas Wegg felt it to be quite out of the question that he could lay his head upon his pillow in peace, without first hovering over Mr Boffin's house in the superior character of its Evil Genius. Power (unless it be the power of intellect or virtue) has ever the greatest attraction for the lowest natures; and the mere defiance of the unconscious house-front, with his power to strip the roof off the inhabiting family like the roof of a house of cards, was a treat which had a charm for Silas Wegg.

As he hovered on the opposite side of the street, exulting, the carriage drove up.

"There'll shortly be an end of you," said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. "Your varnish is fading."

Mrs. Boffin descended and went in.

"Look out for a fall, my Lady Dustwoman," said Wegg.

Bella lightly descended, and ran in after her.

"How brisk we are!" said Wegg. "You won't run so gaily to your old shabby home, my girl. You'll have to go there, though."

A little while, and the Secretary came out.

"I was passed over for you," said Wegg. "But you had better provide yourself with another situation, young man."

Mr. Boffin's shadow passed upon the blinds of three large windows as he trotted down the room, and passed again as he went back.

"Yoop!" cried Wegg. "You're there, are you? Where's the bottle? You would give your bottle for my box, Dustman!"

Having now composed his mind for slumber, he turned homeward. — Book Three, Chapter 7, "The Friendly Move Takes Up a Strong Position," p. 214-215.

Commentary

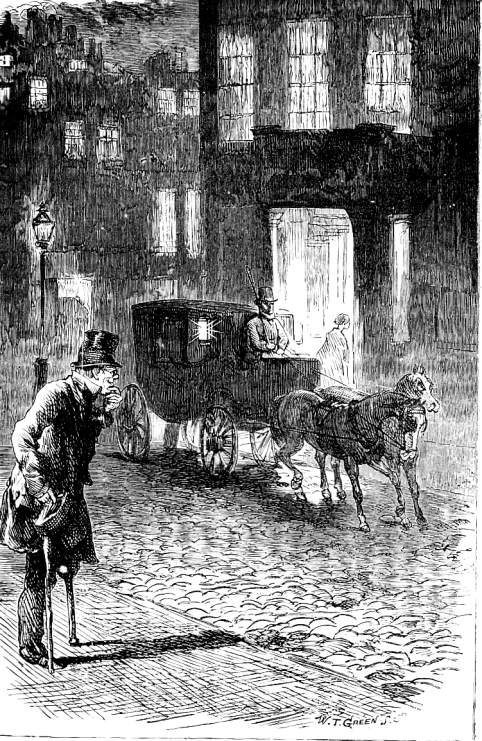

Thus ends Part Twelve (April 1865) in the monthly serial, as Dickens leads readers to believe that the old will that Wegg has discovered and that now resides in Mr. Venus's shop will result in Boffin's having to give in to the partners' blackmail scheme and to buy them off handsomely in order to suppress this document in favour of that which left him principal legatee. The scene in the Mahoney sequence is in fact a re-working of the final April 1865 Marcus Stone illustration, The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin, so that Mahoney has agreed with the original illustrator as to the importance of the scene in setting up false expectations in the reader as part of the novel's texture of duplicity, disguise, conspiracy, and deceit. The new will is in fact our old detective-story friend the red herring.

Since it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the scene outside the Boffin mansion is best considered in light of the changes in composition and emphasis that he effected upon the Marcus Stone original serial illustration. Although Mahoney sometimes rejects Stone's notions, here as in The Dutch Bottle in the twelfth monthly part, the Household Edition illustrator has borrowed directly from Stone, foregrounding the speaker and throwing a departing figure (presumably that of Mrs. Boffin in the lighted doorway) well to the rear, so that the viewer takes in the scene from the perspective of the envious Silas Wegg, just as the text does. Mahoney's illustration continues to construct an atmosphere of suspicion and anticipation that is crucial at this point in the novel, weaving together the plot strands of avarice, mistrust, surveillance, and conspiracy. Whereas Boffin is merely pretending (largely for Bella's benefit) to be consumed with avarice, Wegg is genuinely hoping — against reason — to appropriate all of Boffin's wealth and send both the haughty Secretary and the vain young lady packing.

In Mahoney's treatment, Wegg does not merely smile knowingly (as in Stone's version), but shakes the hatbox dismissively at the carriage, symbol of the Boffins' new-found social status in contrast to the disgruntled pedestrian Wegg. Mahoney has positioned Wegg much further away from the carriage, so that, in the darkness, he would probably be invisible to the occupants of the vehicle as it pulls up at the well-lit entrance. Already the carriage is in motion in the 1865 illustration, whereas it is still stopped at the mansion's front door in the 1875 plate, the horses woodenly static. Stone has chosen to emphasize the mansion's brilliantly lit windows and the carriage lantern as emblems of nouveau riche conspicuous consumption, for this is the exalted, luminescent sphere of ease and affluence that envious, malcontented Silas Wegg, in the outer darkness, yearns to enter in his own right and not merely as a servant or employee of the Golden Dustman. Curiously, Mahoney has muted this effect of light versus darkness in favour of foregrounding the figure of Wegg in a pool of light (perhaps implying a street lamp) and, at the bottom of the plate, a sewer-grate, the ruled lines and kerb curving away from Wegg towards the drain, his proper social station. The wholly new element is the area railing to the right of Wegg, through which the illustrator may be implying that Wegg's hopes of taking Boffin's place as a man of property are going to be ultimately fruitless.

Wegg and Boffin in the original and later editions, 1865-1910

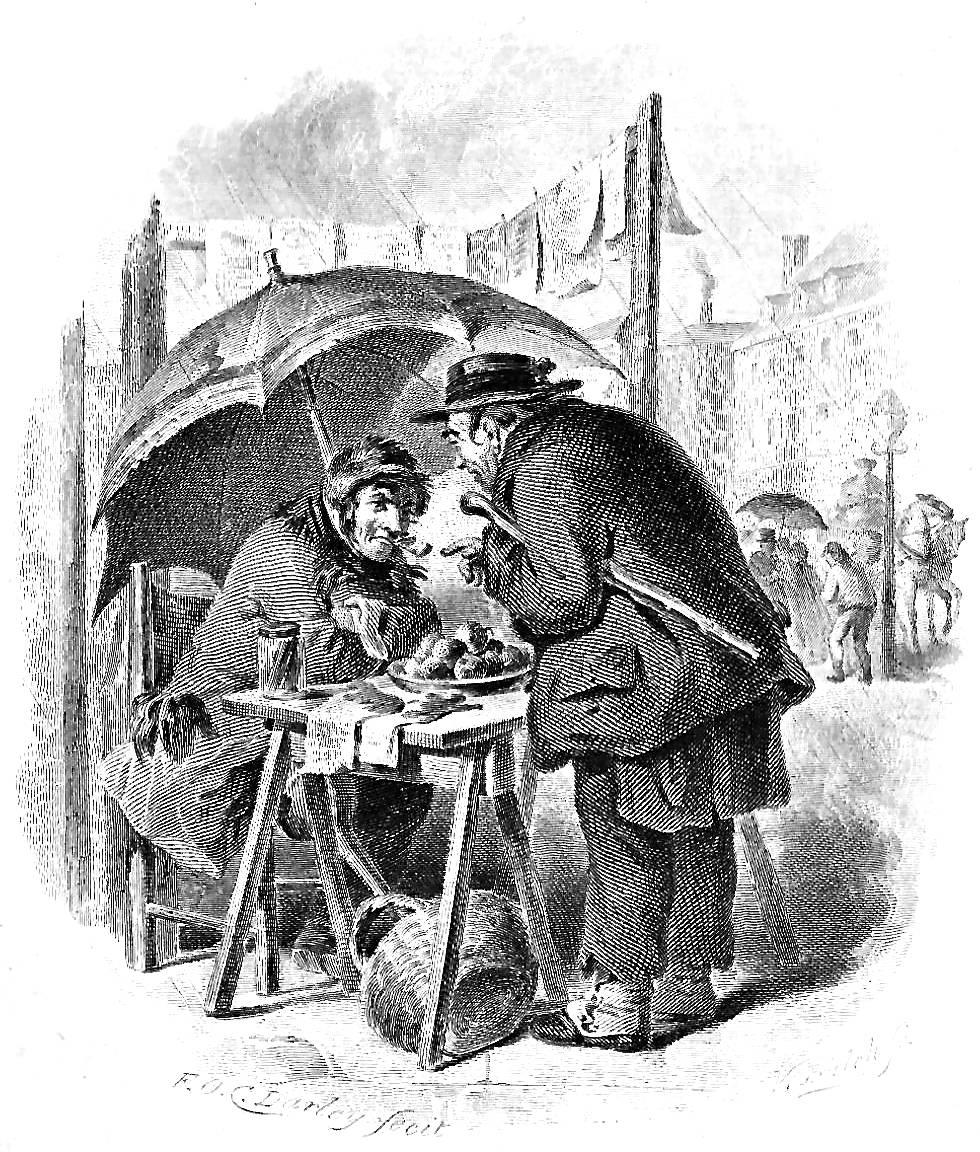

Left: Marcus Stone's April 1865 serial illustration of Wegg's gloating over what he feels will be the consequences of his discovery of another Harmon will, The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin. Centre: Clayton J. Clarke's character study of the envious, one-legged misanthrope, Silas Wegg (1910). Right: F. O. C. Darley's depiction of Wegg as a vendor and Boffin as a peculiar customer, Mr. Boffin engages Mr. Wegg (1866). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 1 January 2016