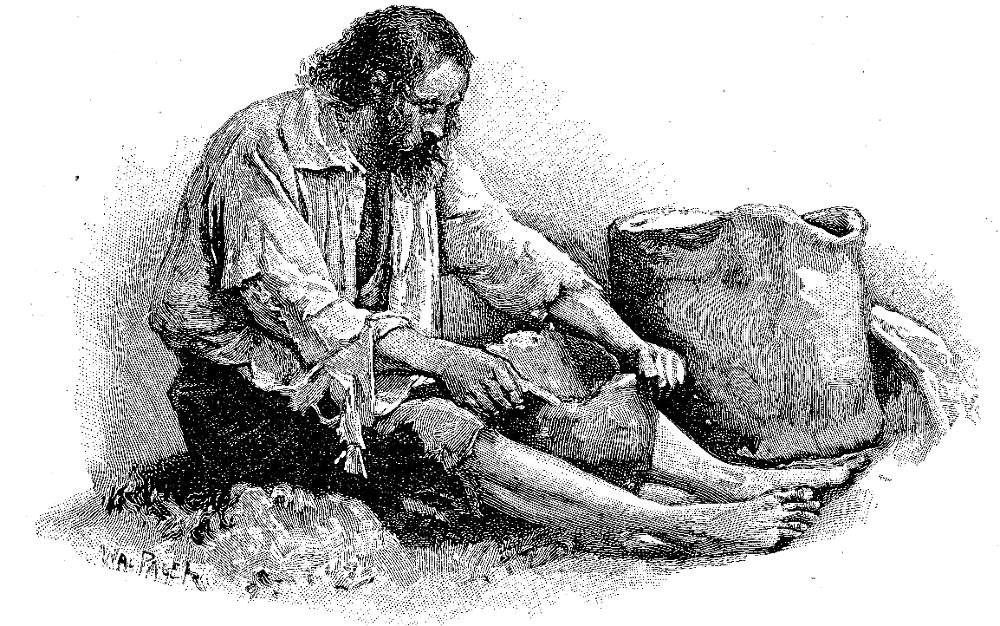

What odd, misshapen, ugly things I made (p. 86) contrasts Crusoe's effectiveness as a basket-weaver. Middle of page 89, vignetted: approximately 11 cm high by 12 cm wide, signed "Wal Paget" lower left.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

It would make the reader pity me, or rather laugh at me, to tell how many awkward ways I took to raise this paste; what odd, misshapen, ugly things I made; how many of them fell in and how many fell out, the clay not being stiff enough to bear its own weight; how many cracked by the over-violent heat of the sun, being set out too hastily; and how many fell in pieces with only removing, as well before as after they were dried; and, in a word, how, after having laboured hard to find the clay —to dig it, to temper it, to bring it home, and work it—I could not make above two large earthen ugly things (I cannot call them jars) in about two months’ labour. [Chapter IX, "A Boat," page86]

Commentary: The Pragmatic Potter

Crusoe is quite prepared to admit that the products of his handiwork are not up to the standards of a European artisan, but unlovely though they may be his pots will serve a practical purpose. Crusoe's pottery therefor exemplifies the pragmatism that Jean-Jacques Rousseau so admired in Robinson Crusoe. Aesthetics must give way to utility under such dire circumstances.One man cannot do all things well, Defoe implies. Whereas the colonists later adapt Crusoe's exemplary basket-making to house-construction later in the novel, his pots are merely good enough for cooking.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 30 April 2018