Left: The Stoppage at the Fountain: Book II, Chapter 7 (for August 1859; issued 25 June in weekly numbers). Right: Mr. Stryver at Tellson's Bank: Book II, Chapter 2 (for August 1859; issued 6 July in weekly numbers). [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

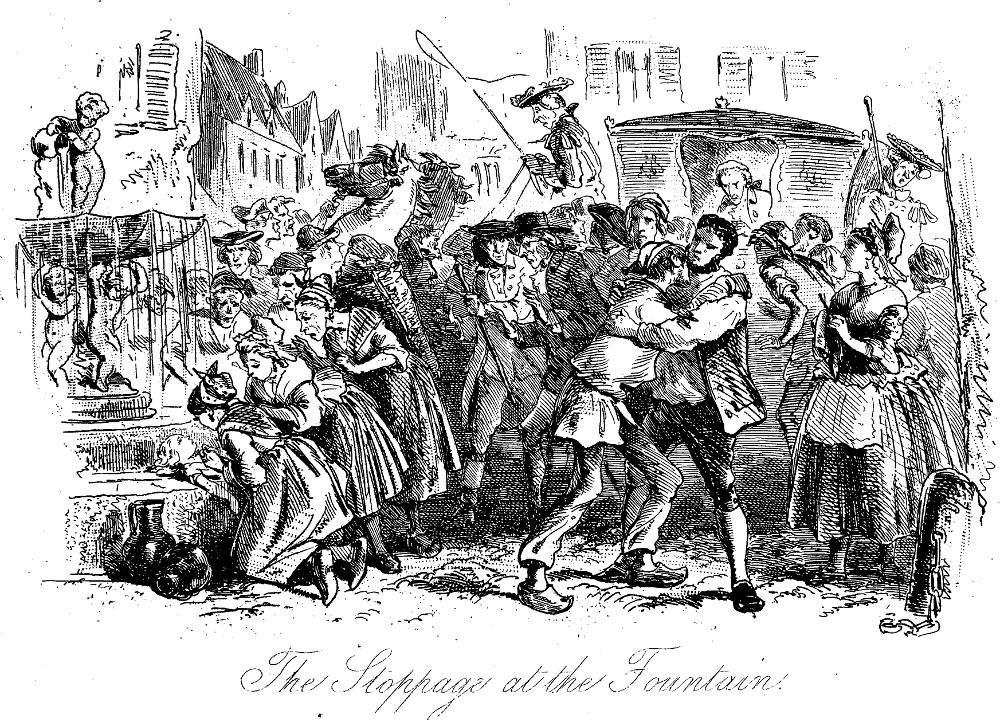

Once again, Phiz illustrates incidents from early and late in the instalment, the former an outdoor Paris scene charged with a Baroque sense of movement and drama, the latter a mundane genre scene set indoors in London. In The Stoppage at The Fountain, the action swirls around twin vortices: to the left, women lament over the dead child in a pose reminiscent of Breughel's Massacre of the Innocents and Giotto's Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The child has been laid at the base of a fountain literally bubbling over with life-giving waters, which pour from the water-pot of the presiding cherub above towards the other putti who support him, the streaming waters complementing the lachrymose state of the chorus of mourners. To the right, the burly Defarge (garbed as in The Shoemaker, left, but this time facing us) comforts the anguished father, Gaspard, the road-mender whose labours are so necessary to the Marquis's sating his desire for speed. The dead child's lack of animation contrasts with the lively poses of the stone cherubs of the gushing fountain, suggestive of an outpouring of tears.

Above the heads of the mixed proletarian and bourgeois crowd the twin towers of Nôtre Dame loom over the shrewd, calculating visage of the Marquis and the disconcerted face of his driver as the horses rear, out of control. Women cry, men gesticulate, while calmly (stage left) the reporter of the ancien regime's wrongs, Madame Defarge, knits the particulars of the incident (especially the name "Evrémonde") into her coded transcript. Above this highly partial recorder of events a lackey regards with apprehension the elements of the crowd outside our field of vision, as if he, the carriage, Monseigneur, and even the horses are about to swept away by the human tidal wave. In a sense, then, the highly dramatic tableau is Phiz's thesis-piece about the causes of the French Revolution: a callous nobility, supported by the established church, oppresses an increasingly restive third estate composed of critical professionals (note the well-dressed bourgeoisie, centre) and emotional proletarians. Phiz has provided his usual symbolic commentary in details of setting: the typical French houses and louvered window-shutters (stage right), the overturned water-pot (indicative of the young life senselessly spilled upon the Paris pavement), and the stone post and chain (stage left). Had the chain been secured, the carriage would not have been free to rattle through the densely populated areas of the capital at top speed, its driver and occupant heedless of pedestrians. Similarly, were France's laws in proper observed and enforced, insensitive noblemen such as the Marquis would not have been able to ride roughshod over the rights of the peasantry.

In the Parisian square, the marble children form a second chorus of grief, their physical contortions reflecting the inward agitation of the tragic chorus of women. In Paris, all faces are animated to suggest discord: accusation, shock, disbelief, and grief are written on all faces but those of the detached observers, the watchful, cold-hearted Marquis and his lower-middle-class counterpart, Madame Defarge. In the Parisian scene, the fountain, the houses, and in particular the clogs clearly establish the scene's context. The clogs, suggestive of social class as well as nationality, are foiled by the adults' shoes and the children's bare feet in the succeeding month's plate. Finally, the overall movement, right to left, is unimpeded in both scenes: the direction as suggested by the faces of all present is reinforced by the horses' heads, left of center.

One wonders to what extent these details and the overall conception of both scenes originated in Phiz's imagination rather than Dickens's text. The passage of the Marquis' carriage, for example, is marked by "women screaming before it, and men clutching each other" (Book II, Chapter 7, p. 40), both of which Phiz's Paris scene includes; "there was a loud cry from a number of voices, and the horses reared" seems to be the precise moment that Phiz has chosen to illustrate. However, while Dickens has "twenty hands at the horses' bridles" (41), Phiz has rendered a single hand, and, more significantly, the "tall man in nightcap" (Gaspard) is not captured in the act of catching up his dead son, depositing the corpse at the fountain's base, and "howling over it like a wild animal." Rather, "some women [are already] stooping over the motionless bundle" (42), "silent, however, as the men." Nowhere in the text does Defarge comfort Gaspard as he does in Phiz's plate. Thus, we can see which textual hints the artist took up, which he disregarded, and how he synthesized several pages of text into a single illustration that impresses its powerful poses and juxtapositions upon the mind of the reader, ready to be called forth in the next month's illustration of a London street scene (The Spy's Funeral).

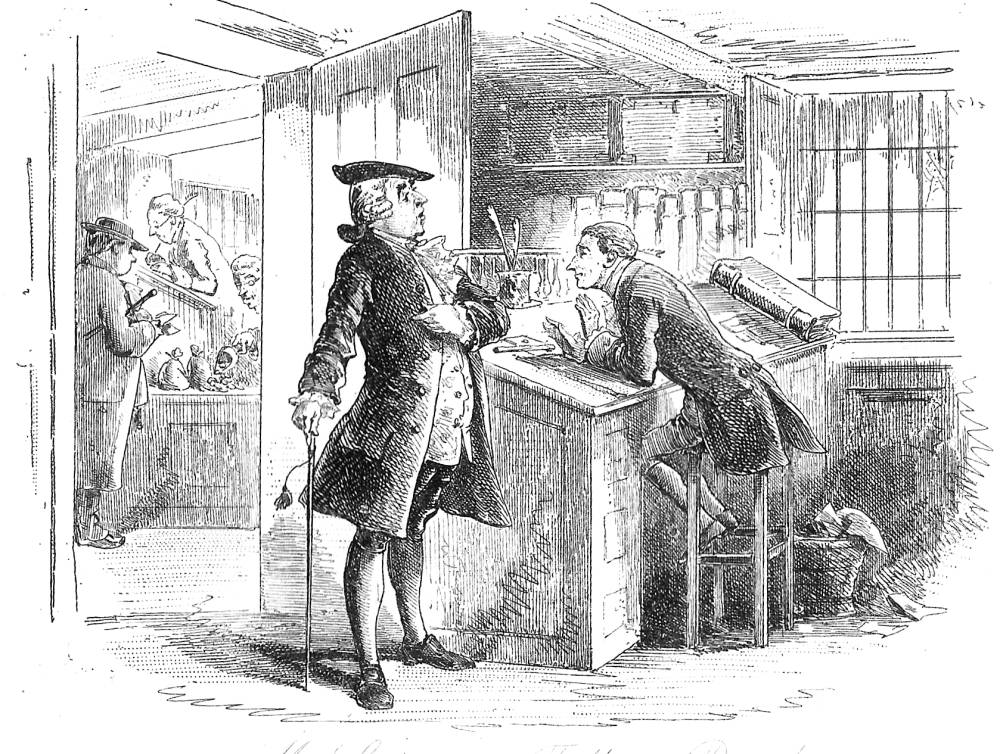

In contrast to the violence and rampant emotionalism of The Stoppage at the Fountain, in Mr. Stryver at Tellson's Bank, Phiz presents a quiet scene of "business as usual" occupied by just a handful of tranquil individuals: pompous and self-important, meticulously dressed (although slightly overweight and top-heavy), attorney Stryver, a professional like some of the figures in the former plate, chats with Mr. Lorry, perched on his stool in the counting house. Beside the clerk a great ledger, closed, reposes on the long counter; undoubtedly it contains records of recent financial transactions, some of which perhaps involve French clients of the Paris house. Certainly, the recording of discrete moments is common to both the August plates. Behind the seated Lorry's head, eight ledgers of varying height and width attest to the house's prosperity, the result of such transactions as that depicted stage right, where a well- dressed gentleman (again carrying that symbol of patriarchal authority and noble status, a cane) is apparently depositing three bags of coins, which one clerk tells while another — like Mr. Lorry, perched on a stool — records. This, then, is the dispassionate counterpart of The Stoppage at the Fountain, for here the wealth of the aristocracy, derived from their abuse of the Social Contract, is tallied by clerks in respectable frock-coats and kept secure by iron bars at the windows.

Other Illustrated Editions (1859-1910)

- Hablot K. Brown or 'Phiz' (16 illustrations, 1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior (8 illustrations, 1867)

- Fred Barnard (25 illustrations, 1874)

- A. A. Dixon (12 illustrations, 1905)

- Harry Furniss (32 illustrations, 1912)

Related Material

- Phiz's Monthly Wrapper

- French Revolution

- Images of the French Revolution from Various Editions of A Tale of Two Cities (1859-1910)

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859): A Model of the Integration of History and Literature

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. “Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Illustrated: A Critical Reassessment of Hablot Knight Browne's Accompanying Plates.” Dickens Studies Annual. 33 (2003): 109-158.

Browne, Edgar. Phiz and Dickens As They Appeared to Edgar Browne. London: James Nisbet, 1913.

Cayzer, Elizabeth. "Dickens and His Late Illustrators. A Change in Style: Phiz and A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian 86, 3 (Autumn, 1990): 130-141.

Cohen, Jane R. "Part Two. Dickens and His Principal Illustrator. Ch. 4. Hablot Browne." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980. Pp. 61-124.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 7 May through 3 December 1859.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities: A story of the French Revolution. Project Gutenberg e-text by Judith Boss, Omaha, Nebraska. Release Date: September 25, 2004 [EBook #98].

Dickens, Charles. (1859). A Tale of Two Cities, ed. Andrew Sanders. World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Dickens, Charles. (1859). A Tale of Two Cities, ed. George Woodcock. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Vann, J. Don. "A Tale of Two Cities in All the Year Round, 30 April—26 November 1859." New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 71-72.

Created 23 October 2018

Last modified 19 January 2026