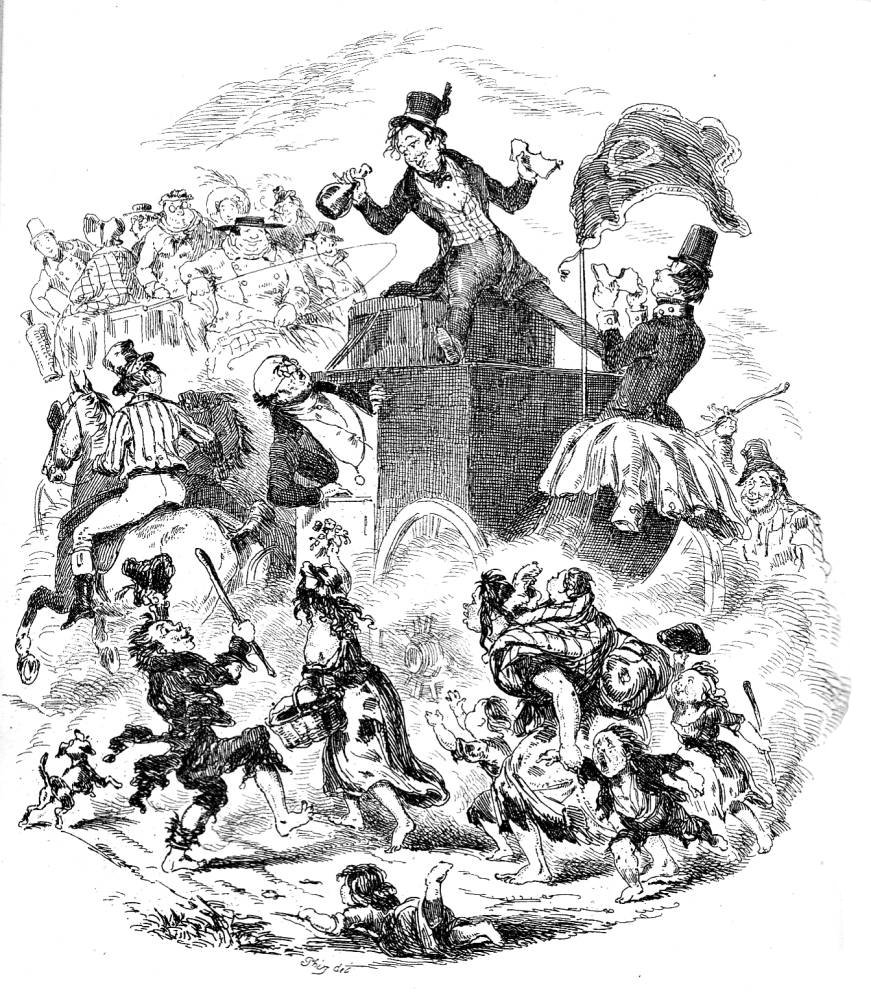

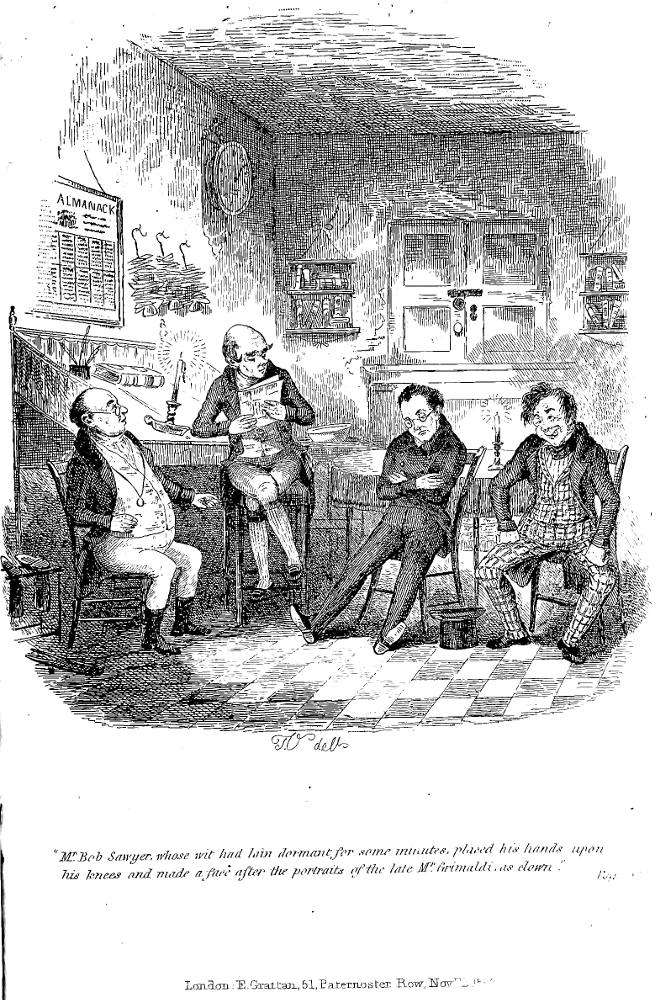

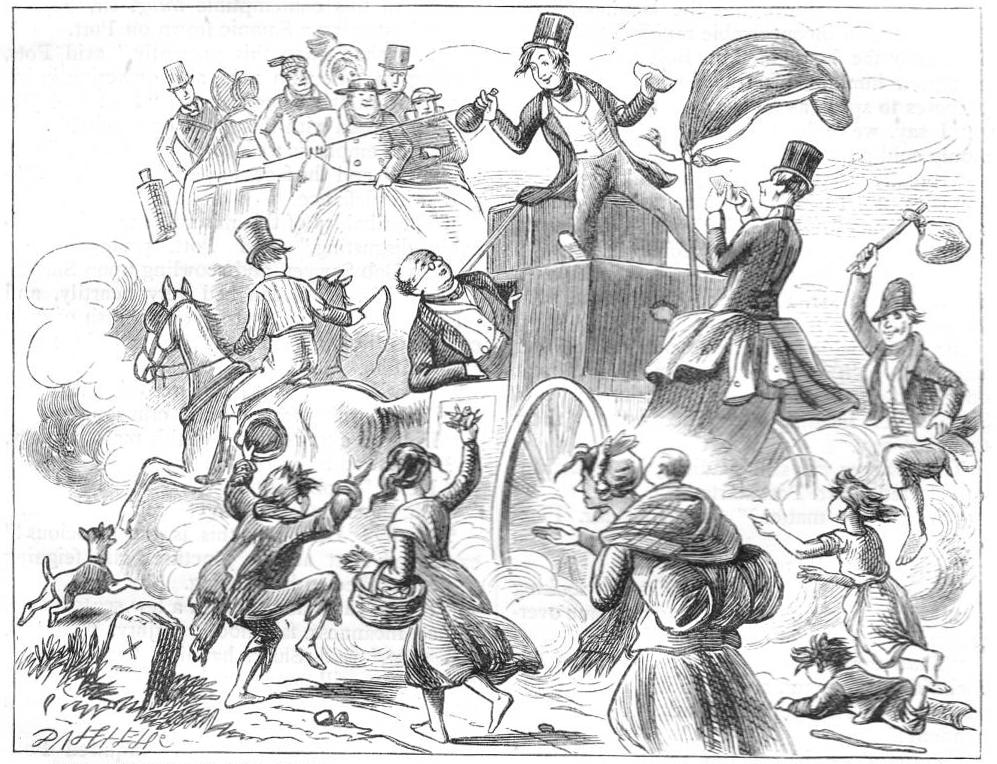

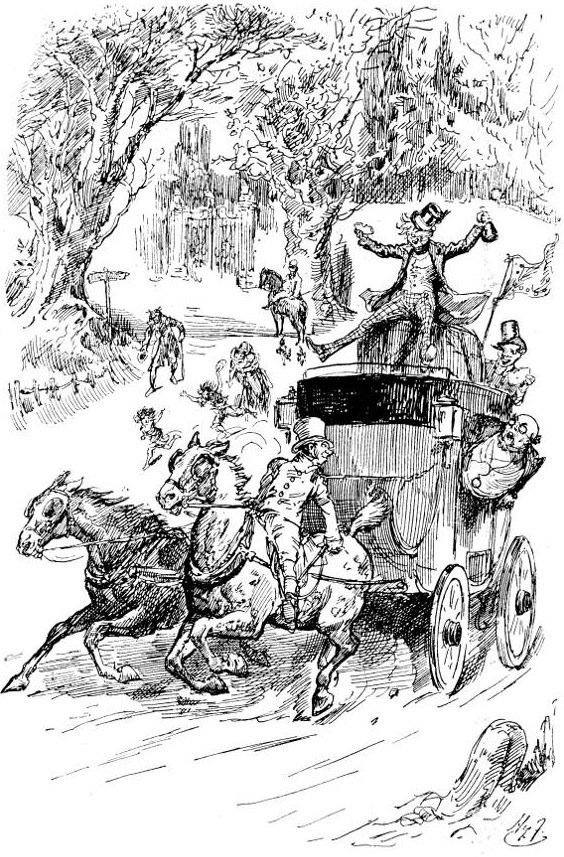

Mr. Bob Sawyer's mode of travelling

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

October 1837

13 cm x 11.2 cm (5 by 4 ¼ inches), vignetted

Dickens's Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, Chapter L, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing II, 712.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Details

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham.