Betteredge Writing His Account — uncaptioned head-piece for the "The Story. First Period." — fourth illustration in the Doubleday (New York) 1946 edition of The Moonstone, p. 9. 3.2 x 6.4 cm. [Commissioned by Franklin Blake to record his perceptions of what happened at Rachel Verinder's birthday dinner on 21 June 1848, including the events leading up to the theft of the Moonstone, and events which he observed afterwards, the estate steward, Gabriel Betteredge is writing pages by candle-light, and therefore probably in the evening, after a day's work. Prominence accorded the ink-drawing by virtue of its heading the fitst and principal narrative alerts the reader to Collins's "testamentary" method of recounting the story.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

In the first part of Robinson Crusoe, at page one hundred and twenty-nine, you will find it thus written:>/p>

"Now I saw, though too late, the Folly of beginning a Work before we count the Cost, and before we judge rightly of our own Strength to go through with it."

Only yesterday, I opened my Robinson Crusoe at that place. Only this morning (May twenty-first, Eighteen hundred and fifty), came my lady's nephew, Mr. Franklin Blake, and held a short conversation with me, as follows:

"Betteredge,” says Mr. Franklin, “I have been to the lawyer’s about some family matters; and, among other things, we have been talking of the loss of the Indian Diamond, in my aunt’s house in Yorkshire, two years since. Mr. Bruff thinks as I think, that the whole story ought, in the interests of truth, to be placed on record in writing — and the sooner the better."

Not perceiving his drift yet, and thinking it always desirable for the sake of peace and quietness to be on the lawyer’s side, I said I thought so too. Mr. Franklin went on.

"In this matter of the Diamond," he said, "the characters of innocent people have suffered under suspicion already — as you know. The memories of innocent people may suffer, hereafter, for want of a record of the facts to which those who come after us can appeal. There can be no doubt that this strange family story of ours ought to be told. And I think, Betteredge, Mr. Bruff and I together have hit on the right way of telling it."

Very satisfactory to both of them, no doubt. But I failed to see what I myself had to do with it, so far.

"We have certain events to relate," Mr. Franklin proceeded; "and we have certain persons concerned in those events who are capable of relating them. Starting from these plain facts, the idea is that we should all write the story of the Moonstone in turn — as far as our own personal experience extends, and no farther. We must begin by showing how the Diamond first fell into the hands of my uncle Herncastle, when he was serving in India fifty years since. This prefatory narrative I have already got by me in the form of an old family paper, which relates the necessary particulars on the authority of an eye-witness. The next thing to do is to tell how the Diamond found its way into my aunt’s house in Yorkshire, two years ago, and how it came to be lost in little more than twelve hours afterwards. Nobody knows as much as you do, Betteredge, about what went on in the house at that time. So you must take the pen in hand, and start the story."

In those terms I was informed of what my personal concern was with the matter of the Diamond. If you are curious to know what course I took under the circumstances, I beg to inform you that I did what you would probably have done in my place. I modestly declared myself to be quite unequal to the task imposed upon me — and I privately felt, all the time, that I was quite clever enough to perform it, if I only gave my own abilities a fair chance. Mr. Franklin, I imagine, must have seen my private sentiments in my face. He declined to believe in my modesty; and he insisted on giving my abilities a fair chance.

Two hours have passed since Mr. Franklin left me. As soon as his back was turned, I went to my writing desk to start the story. — "The Story. First Period. Loss of the Diamond (1848). The events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," p. 9-10.

Commentary: The "Testamentary" Rhetorical Strategy

Alethea Hayter memorably describes the narrative structure of The Moonstone as one of "Chinese-box intricacy." Structured on the chain of evidence at a criminal trial, the novel presents multiple narrators (including Betteredge, Clack, Bruff, Blake, Jennings, Cuff, Cuff's man, Candy, the Captain, and Murthwaite) and documents (including family papers, Herncastle’s will, Rosanna’s letter, and Jennings's journal of Candy's delirium), each suggesting a slightly different knowledge or interpretation of events. The reader must penetrate the resulting web of multiple "intersecting narratives" and "frequently shifted point of view” in order to solve the mystery of the stolen diamond. As Sandra Kemp argues, the novel thus creates intense self-consciousness about “the manipulation of stories and the ways they can be told." We suggest that the illustrated version of The Moonstone that Harper's readers encountered in 1868 added an intricate visual layer to this already complex narrative structure. — Leighton and Surridge, p. 209-210.

Whereas the original serial illustrations in Harper's Weekly made American readers in 1868 aware of the initial and subsequent physical and temporal settings (India in 1799 and Yorkshire in 1848) and introduce Betteredge as a liveried butler in "My Lady and Miss Rachel regret that they are engaged, Colonel" (11 January 1868, p. 21), later editions have thrown Betteredge, usually wearing the clothing of a "gentleman's gentleman," well into the background, as in F. A. Fraser's "The Sergeant pointed to the boot in the footmark, without saying a word" (1890) and John Sloan's 'Lord bless us! it was a Diamond!' (1908). In fact, Betteredge the character is of secondary importance, but Betteredge the narrative voice casts a significant colouration over events in the first half of the book, although this filtering is far more subtle and agreeable than that offered by Miss Clack's account. The original magazine wood-engravings, although highly informative, juxtaposed against the text and action of each instalment, nevertheless fail to foreground Collins's rhetorical strategy of utilising instead of a single, omniscient narrator a series of first-person "testaments" — a method which came to him after he had attended a criminal trial in 1856, "and was impressed both by the manner in which a chain of evidence could be forged from the testimonies of successive witnesses" (Stewart 12). Sharp's headnote illustration draws the reader's attention to the fact that sundry voices with considerable knowledge of certain parts of the story will enter their "evidence" into the reader's consciousness. The original illustrations do not operate in the way that Sharp's illustration here does, for it foregrounds the reader's being introduced to Betteredge in the role of a narrator and as a stand-in for writer Wilkie Collins. William Sharp shows the old, bespectacled steward writing his account, according to Franklin Blake's request, rather than recounting his portion of the story orally, although throughout this opening portion of the novel one has a strong sense of Betteredge as a distinct "voice" and personality — that of a seventy-year-old family retainer with weak eyesight and sometimes antiquated, sometimes quaint notions. Remarks Collins of this technique,

It came to me then that a series of events in a novel would lend themselves well to an exposition like this. Certainly the same means, employed here, I thought, one could impart to the reader that acceptance, that sense of belief, which I saw produced here by the succession of testimonies so varied in form and nevertheless so strictly unified by their march toward the same goal. The more I thought about it, the more an effort of this kind struck me as bound to succeed. Consequently, when the case was over, I went home determined to make the attempt. — Wilkie Collins, cited by Stewart, 12.

Relevant Plates from Earlier Editions Showing Betteredge: 1868, 1890, and 1908.

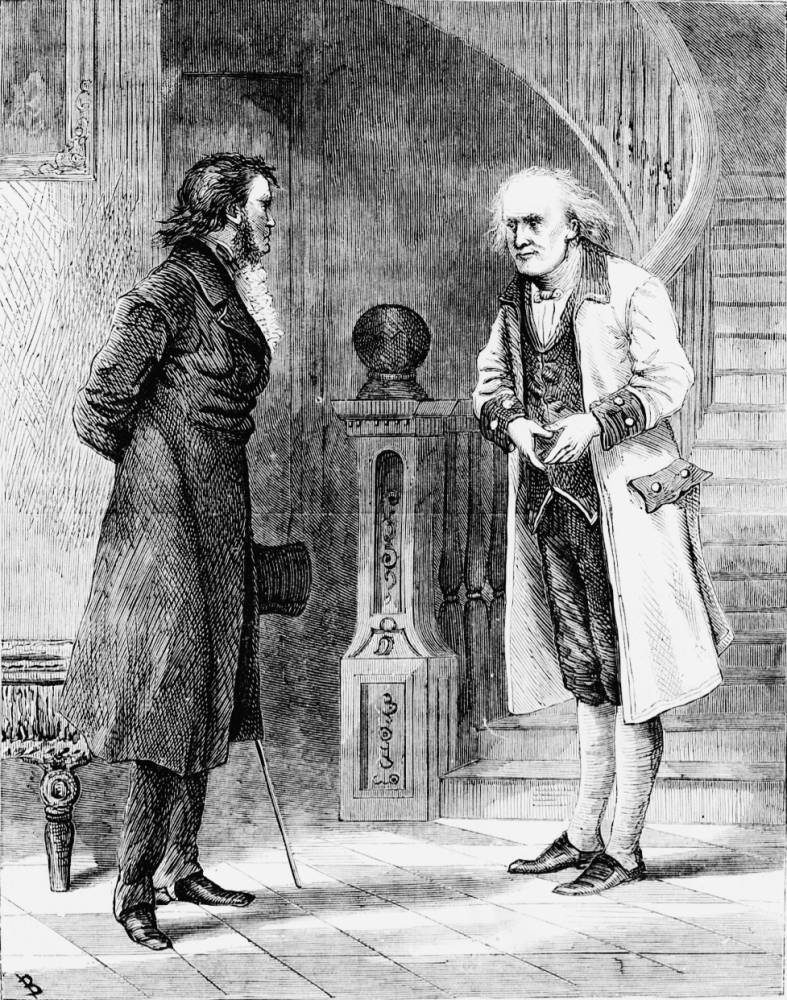

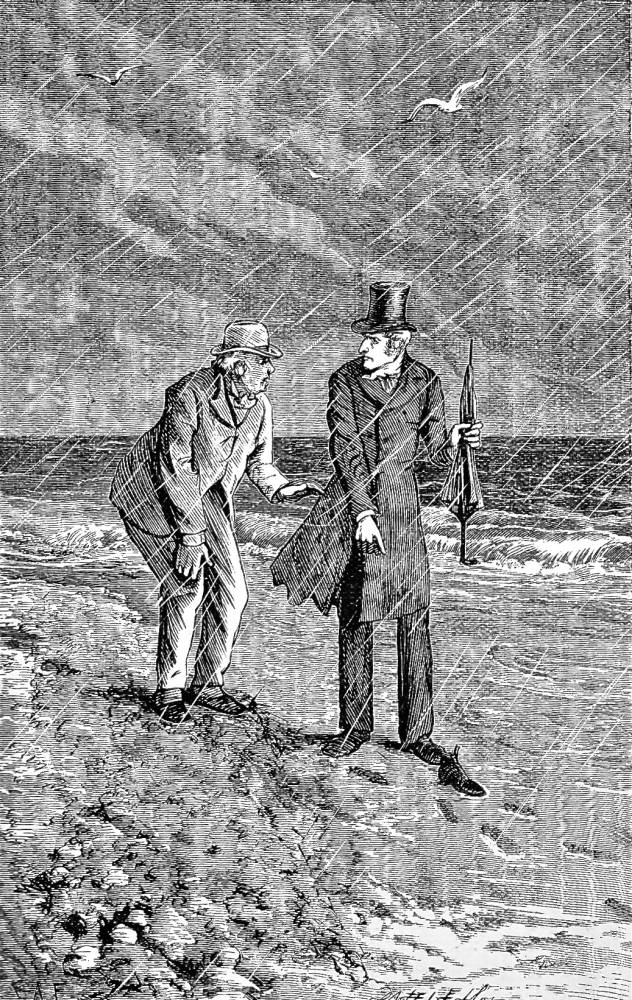

Left: The original serial wood-engraving in Harper's of Betteredge's refusing to admit an aged John Herncastle at Lady Julia's London townhouse, "My Lady and Miss Rachel regret that they are engaged, Colonel" (11 January 1868). Centre: F. A. Fraser's realisation of the scene in which Betteredge and Sergeant Cuff trace Rosanna Spearman's bootprints to the Shivering Sand, "The Sergeant pointed to the boot in the footmark, without saying a word" (1910). Right: John Sloan's realisation of the scene in which Rachel shows her cousins the Moonstone, 'Lord bless us! it was a Diamond!' (1908). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Introduction to the Sixty-six Harper's Weekly Illustrations for The Moonstone (1868)

- The Harper's Weekly Illustrations for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (1868)

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone.

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. with sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-503.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone. With 19 illustrations. The Works of Wilkie Collins. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900. Volumes 6 and 7.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 7-24.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Last updated 27 September 2016