In the December 1849 number, we overhear the following exchange between the naive David Copperfield and the cynical but well-informed James Steerforth, who clearly serves as Dickens's mouthpiece as David, following his Aunt Betsey's cue, contemplates a legal career in the ecclesiastical court usually called "Doctors' Commons":

"What is a proctor, Steerforth?" said I.

Why, he is a sort of monkish attorney," replied Steerforth. "He is, to some faded courts held in the Doctors' Commons — a lazy old nook near St. Paul's Churchyard — what solicitors are to the courts of law and equity. He is a functionary whose existence, in the natural course of things, would have terminated about two hundred years ago. I can tell you best what he is, by telling you what Doctors' Commons is. It's a little out-of-the-way place, where they administer what is called ecclesiastical law, and play all kinds of tricks with obsolete old monsters of acts of Parliament. . . . It's a place that has an ancient monopoly in suits about people's wills and people's marriages, and disputes among ships and boats." [Charles Dickens, David Copperfield, Ch. 23, "I Corroborate Mr. Dick, and Choose a Profession," instalment 8, Dec. 1849]

One of the original eight Sketches by Boz (11 October 1836, in The Morning Chronicle) was also entitled "Doctors' Commons." Dickens never actually worked there as a "Proctor" as his protagonist David does, but as a young shorthand reporter he had some experience of the place, which he came to regard as farcical and venial in the extreme. It was indeed "old-fashioned," having been founded in the thirteenth century and was not decommissioned until 1857. According to The Dickens Index:

Its members, who had to be Doctors of Law of either Oxford or Cambridge University, had the sole right of appearing in ecclesiastical (including divorce) probate, and admiralty courts, while proctors, who did the work of solicitors, were attached to them. [76]

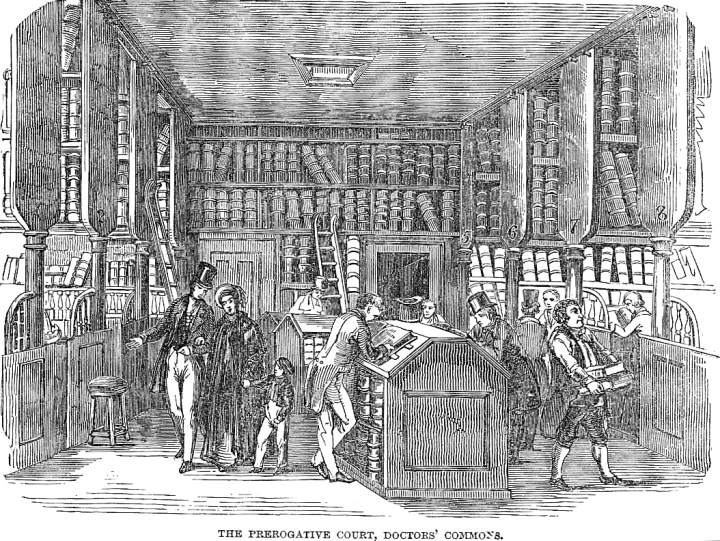

The twenty-second chapter of Thomas Miller's Picturesque Sketches of London, Past and Present, serialised in The Illustrated London News, describes in detail the appearances and behaviours of those who resort to the Prerogative Court, Doctors' Commons, "the chambers where the wills of the dead are deposited" (399).

A strange place is that Prerogative Court, a fine picture of the great out-of-the-door world, for there Hope and Despair stand sentinels at the door, and the living seem to jostle the dead in their eager hurry to hunt after what those in the grave have left them. There is a smell as of death about the place, as if grey old departed spirits lurked in the musty folios, and had scattered their ashes amid the yellow and unearthly-looking parchments, which rise up again in clouds of dust while you turn over the mouldy and crackling leaves, making you sneeze again; while an hundred old echoes take up the sound, until every volume seems to shake and laugh, and mock you as if the grim old dead found it a rare spot to make merry in — to "mop and mow," and play off a thousand devilish antics upon the living. That court is the great mart of merriment and misery, and its open doors too often lead to madness; groaning, and moaning, when they are opened or shut, as if the spirits within wailed over those who come in search of wealth. . . .

Affording colloquial Cockney humour, the white-aproned and street-wise porters in the vicinity of the Commons, self-taught proctors who have imbibed considerable knowledge of the protocols and procedures of the place, are ever ready to advise inexperienced legatees: "God bless you, sir, we knows plenty of people what's got thousands, as never expected to have a blessed meg whatsumdever."

Young and old, men and women, express in their faces and postures the whole gamut of human emotion as they peruse these documents and learn of their ill or good fortune. One youth, for example, sits at one the desks,

His fists . . . clenched, the nails of his fingers imbedded in the palms of his hands, his teeth set, his eyebrows knit: he strikes his hat as he places it on his head, closes the door with a loud slam, and curses the memory of the dead man, because he has left a reckless spendthrift just enough to live on all his life without working, yet so bequeathed it that he can but draw a given sum monthly. He is savage because he cannot have the whole legacy at once in his possession. If he could, he would be likely enough to squander it all away in a single night at some notorious gambling-house.

The Miller persona of piece for the ILN, Godfrey Malvern, having waxed philosophical the Commons being the repository for the last will and testament of the "immortal" Shakespeare ("On that document his far-seeing eyes looked"), hyperbolically describes the grim-faced, old judge, "deaf and blind," as having enjoyed this sinecure for hundreds of years: “He acts but for the dead — the living he can neither hear nor see — but ever sits with his elbow resting on a pile of musty volumes, mute as a marble image. It is a place filled with solemn associations — the ante-room of Life in Death.”

The Prerogative Court, Doctors' Commons. From the 1850 Illistrated London News. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

In a less philosophical vein, Dickens followed up on his implicit criticism of the operation of the Doctors' Commons, teaming up with his subeditor G. H. Wills on a journalistic expose in Household Words that fall. In a series of five articles, the pair attacked the institution as hopelessly outdated and painfully slow in processing claims and prosecuting searches.

However, this attitude was nothing new for Dickens, who had lampooned the operations and personages of the Prerogative Court in the 1836 sketch "Doctors' Commons." In this satirical jeu d'esprit, having taken us down "Paul's Chain" and across a quiet and shady cobble-stoned court-yard near St. Paul's Cathedral, the man-about-town walks us through "a small, green-baized, brass-headed-nailed door" (86), and into an ancient wainscoted semicircular apartment where an excommunication hearing is in progress. The antagonists today in the Arches Court are the delightfully named Michael Bumple and ginger-beer vendor Thomas Sludberry, whose altercation had led to a charge of "brawling," which, "under a half-obsolete statute of one of the Edwards," carries the no-longer significant ecclesiastical penalty if the battery occurs "in any church, or vestry adjoining thereto" (88). No matter that nothing physical transpired in the vestry-meeting, and that only heated words of the "You be blowed" variety were actually exchanged:

The red-faced gentleman in the tortoise-shell spectacles took a review of the case, which occupied half an hour more, and then pronounced upon Sludberry the awful sentence of excommunication for a fortnight, and payment of costs of the suit. (89)

When the amiable and eminently practical beverage-seller, clearly a non-practising Anglican or atheist, enquires whether, in exchange for a life sentence, he might be permitted to forego the costs entirely, the judge responds with a look of incredulity and "virtuous indignation," dumbfounded — much to the reader's delight.

After the comedic courtroom interchange, Dickens's observer accompanies us into the Prerogative Office, where clerks are copying deeds and hopeful legatees are poring over thick vellum volumes, searching for the wills of rich, deceased relatives. One little, elderly reader seems utterly perplexed and bewildered by technicalities in the fifty-year-old document he examines. Another seeker, with a hard-featured and deeply wrinkled visage, the very epitome of avarice with toothless mouth and "sharp keen eyes," discovers how he may buy out the interest of a poverty-stricken legatee for a mere twelfth of the estate's true value:

The old man stowed his pocket-book carefully in the breast of his great-coat, and hobbled away with a leer of triumph. That will had made him ten years younger at the lowest computation. (90)

Walking out of the dingy room with its worm-eaten volumes redolent with the odour of the grave, the narrator considers how petty are the greed and hatred, jealousies and revenges of the living when juxtaposed with sightless, soundless nature of eternity in this dilapidated temple of black-letter law:

How many men as they lay speechless and helpless on the bed of death, would have given worlds but for the strength and power to blot out the silent evidence of animosity and bitterness, which now stands registered against them in Doctors' Commons! (91)

References

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U P, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield. The Centenary Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens in 36 Volumes. London & New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

—. "Doctors' Commons." Ch. 7, Sketches by Boz. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford and Toronto: Oxford U P, 1987. Pp. 86-91.

Miller, Thomas [pseudonym: Godfrey Malvern]. "Prerogative Court, Doctors' Commons." Ch.12, Picturesque Sketches of London, Past and Present. The Illustrated London News, 1 June 1850. Page 399.

Last modified 15 July 2010