III. The Political Ghost and Women’s Issues

he Victorian apparition was as a flexible means of analysing the mind, but it also functioned as an agency of political interrogation. This theme has been taken up by a number of modern critics. Andrew Smith conceptualizes the ghost as a ‘critical tool’ (5) and explores its application to a number of topical issues and social debates. Smith is centrally concerned with the genre’s ‘associations with economics’ (11) and provides a series of insightful readings of how the spectral can be used to critique capitalism and the workings of money along with its other applications as a method of anatomizing colonialism. Simon Hay takes a parallel view, although his focus is broader, noting how the ghostly charts what he calls the ‘traumatic transition from feudalism to capitalism’ (15); he further explores its commentary on class and social relationships within the cash-nexus. Other commentaries have traced representations of empire and the colonial experience, and the overall emphasis in these interpretations is on the ghost story’s vital engagement with the multifaceted culture that produced it.

In A Christmas Carol, Dickens writes an elaborate paraphernalia of mystical forms to articulate a hard-nosed assessment of capitalism, and there could be nothing clearer than Marley’s sufferings in the after-life as a metaphor for the corrosive power of greed. Dickens’s ‘The Signalman’ is likewise a topical reflection on the unnatural systems of industrialized working: focused on the railwayman’s routine, it critiques a life-style in which the employee has nothing to do most of the time, but what he does do – signalling clear or danger – is of the utmost significance. Demented by the stress of having just one opportunity to perform his duties safely, the signalman conjures a phantom to represent the consequences of making an error, a situation that plays agonizingly on the anxieties of those travelling on the railway in a period when accidents were common. Having experienced a railroad crash in the Staplehurst disaster, Dickens makes his tale into a reflection on a hot topic.

The spectral monkey in Le Fanu’s ‘Green Tea’ is similarly laden with associations. As noted earlier, it could suggest some hidden and deeply repressed anxiety, although recent critics have argued that it represents a broader critique of the cultural incompatibility of Britain and the countries it has colonized. In this interpretation, Le Fanu infuses the creature with a very specific guilt which embodies the iniquity of exploitative colonialism. As Hay explains:

The monkey and the green tea … are connected in that the monkey literalizes the social structures that lie behind the London consumption of green tea, functions [and] functions allegorically as a kind of supernatural cognitive map: the monkey is a tropical creature from the world’s tea-growing regions, so that to be haunted by a monkey … is to be haunted by the tropics, for the tea to bring with it an unwelcome reminder of its colonial origins. [82]

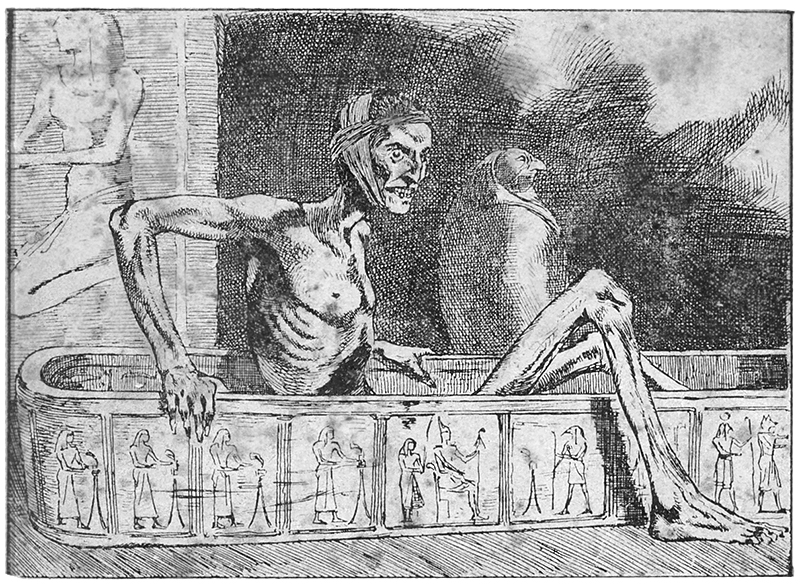

Martin Van Maële's illustration of Arthur Conan Doyle's "Lot no. 249" in Société d'Édition et de Publications, 1906. Source: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/Lot_No._249).

Le Fanu’s bizarre tale might thus read as piece of pragmatic political commentary, a coded reflection on the known rather than the unknown in which, as Nicholas Allen remarks, ‘England’s connection to the global economy [is] figured as a problem at home’ (115) and the ‘homeliness’ of Albion is infected with the ‘unhomeliness’ of the menacingly foreign. Britain’s relationship with its colonies is certainly a major theme, especially in ghost and Gothic tales from the end of the century. Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘Lot No. 249’ (1894) speculates on the values and significance of the dead cultures of Egypt, suggesting that the quaint antiquity represented by a mummy is in fact unnervingly strange and dangerous. The unfamiliarity of countries apparently no more an extension of the Homeland also figures in Rudyard Kipling’s stories of India, which mediate between the spectral and visceral while always emphasising the uncanniness of the imperial encounter.

These texts act as a cathartic release from anxious speculations, negotiating troubling issues from within the ‘safe’ domain of the supernatural fantasy. Moreover, these sociological applications can be gendered; some deal with distinctly masculine interests such as economics and the workings of the empire, while others, written by women, deal with female issues and perspectives.

Women writers provide an extensive treatment of the phantasmal and its symbolic applications, although critics have struggled to find an overarching model of what constitutes the ‘female ghost story’. Feminist commentators, notably Vanessa Dickerson, have argued that writers such as Oliphant used the symbolism of ghostliness to signal women’s marginality in a strictly patriarchal society:

Robbed of place, of space of substance … the Victorian woman paled in the real, the material, the business world [and was only required] to give up, rein in, be silent, be still … The position of the nineteenth century female … was equivocal, ambiguous, marginal, ghostly [and the] ghost corresponded … to the Victorian woman’s visibility and invisibility, her power and powerlessness … [4–5]

Dickerson does not give sufficient consideration of the nuances of class in this analysis and does not seem aware of the fact that she is writing only of female members of the Victorian bourgeoisie; nevertheless, her interpretation is suggestive. An alternative view is taken by Jarlath Killeen, for whom the real ghosts are the men in women’s stories, the ‘male threat’ (93) that put women in a precarious position but denies its responsibility for inequality and remains ‘nebulous’ and ‘intangible’ (85). Again, this reading is provocative if more difficult to support. A third strand is the emphasis on female writing of the ghostly as a metaphor for specific issues which had a direct impact on the way women lived their lives, Each of these theories intertwines and can be applied, and challenged, by reading a series of typical stories.

Dickerson’s notion of female invisibility is partly evidenced by the many tales written by women in which the wives and sisters are typically confined to stereotypical roles as nurturers, mothers and home-makers, and it is especially noticeable that female characters are witnesses to ghostly accounts told by men, rather than telling them themselves. In this role, women are distanced from some of the horrors of direct experience, but support the men who have suffered bizarre encounters. This is the situation in Molesworth’s ‘The Rippling Train’, which closes with the young women reflecting compassionately on the story, and it is matched by the supportive role of the narrator’s sister in Dickens’s ‘The Mortals in the House’ (16–19). These female characters are placed at the edge of the frame, their significance diminished to conventional understandings of women’s status as echoes or shadows of their men. Women’s status is sometimes pointedly shown to be so low as to exclude them altogether or to treat them as irrelevant. Female servants afraid of the haunting are emblematically depicted as too trivial to be taken seriously, and in ‘The Phantom Coach’ Edwards summarizes female marginality by noting that the narrator does not tell his wife of his horrifying ordeal. In these circumstances the women as indeed ghosts – shadows of people too insignificant even to notice as they fade ethereally into the background.

Conversely, it is sometimes the case that female narrators critique male behaviour, challenging the male forces that Killeen regards as the ghostly puppet-masters of the female condition. Elizabeth Gaskell strongly asserts the power of the female voice in ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’. In this story the author doubles her effects by putting words into the mouth of a narrator who is both a woman and a servant, thus firmly locating the narrative in the domain of gender and class marginality. Gifted with female perceptions, the storyteller critiques the brutality of Lord Furnivall and the consequences of his actions: he may be invisible – in Killeen’s terms – but the Nurse makes sure that that his crimes are anything but immaterial. The overall effect is far from sentimental and emphasises the validity of women’s understandings in a world dominated by masculine power.

Gaskell’s approach is characteristically tough and incisive, and the same can be said of many of her co-writers of the supernatural, who offer an allegorical reflection on the most limiting constraints experienced by middle-class women. The process of objectification and the ways in which men reduce women to a visual experience is probed in a series of disconcerting texts. One of the most interesting of these is Amelia Edwards’s ‘The Story of Salome’. Edwards focuses on the idea of male adoration of a glamorous face endowed with ‘large, lustrous, melancholy eyes’ (65), while the dead Salome’s reappearance as an agitated spirit is supposedly animated by her desire to lie among those of the same (Judaic) faith. However, the author subtly points to the way in which the character is purely perceived as an idea of womanhood, a female both beautiful and helpless, without a ‘single male relation to advise her’ (73). Writing as a gay author, Edwards highlights the limitations of masculine attitudes and challenges gender stereotypes.

Running in parallel with this concern is the problem of women’s economic vulnerability and lack of earning power. It is interesting to note that several of the writers – principally Oliphant, Riddell and Braddon – were all hard-pressed, and had to write to live: forced to be both bread-winners and home-makers, all three present analytical accounts of women’s financial problems. The sub-text here is their resistance to male dominance and control: in ‘The Library Window’, for example, Oliphant symbolizes the female desire to work in a profession – a notion exemplified by the vision of a writer toiling at his text – while demonstrating the narrator’s economic helplessness as she is closed in and regulated by her elders and can only survive economically by making a ‘good marriage’. Oliphant also critiques inheritance laws and their capacity to ruin a vulnerable woman. In ‘Old Lady Mary’ she highlights the character’s feckless selfishness, showing how her death has a disastrous impact on her youthful ward; intestate, Mary has made no provision for her dependent. Interestingly, the ghostly situation is figured so that the ghost (Lady Mary) is forced to suffer almost as much as the younger, ‘little Mary’, as she witnesses the consequences of her inaction. Both characters are female, but Oliphant makes a wider criticism of the machinery of inheritance which favours sons and condemns unmarried women to the status of ‘old maids’ and ‘aunties’ who had to exist in poverty on the margins of respectable life.

Braddon's Lady Ducayne, "if not quite a ghost then at least one of the time-defying undead" (source Strand Magazine, 188), illuatrated by Gordon Browne.

Nor is it the case that working for a living is necessarily the best option, and ghost writers several times provide a riposte to the apparently liberating ambitions of the ‘New Woman’ of the 1890s. Braddon uses supernatural devices to show how young women’s careers as workers is often as tenuous as not working at all, and with other threats and indignities. ‘Good Lady Ducayne’ (1896) offers a disarmingly ‘modern’ commentary, noting the practicalities of work in realistic detail: ‘Bella Rolleston had made up her mind that her only chance of earning her bread and helping her mother to an occasional crust was by going out in the great unknown world as a companion to a lady’ (259). Braddon further specifies the vulgar details of the employment agency and all seems practical and down-to-earth. However, Bella becomes the victim of Lady Ducayne, who if not quite a ghost then at least one of the time-defying undead. Grotesquely described as a vampire-like denizen of the grave, she appropriates Bella’s youth, an act of parasitism which acts as a metaphor of the economic exploitation of young women. Literally sucking Bella’s life, Lady Ducayne represents the entrenched forces of privilege and tradition that ensnare female workers and hold them firmly in submissive roles.

Related Material

- Introduction: The Haunted Text

- I. Doubts and Affirmations: the Purposes of the Victorian Ghost Story

- II. The Psychological Ghost

- IV. Some Final Thoughts on the Victorian Ghost Story

- Bibliography (primary and secondary sources)

Created 2 June 2021