[Click on images to enlarge them and for additional information. Links, added images added, and formatting by George P. Landow.]

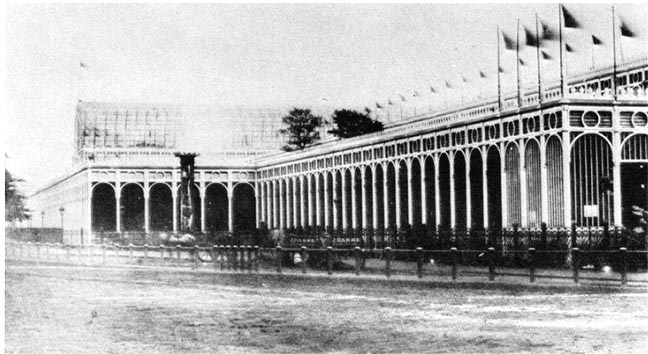

General View of the Exterior of the Building — the first image in Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, from the originals painted for ... Prince Albert, by Messrs. Nash, Haghe and Roberts. London, 1854. Courtesy of the British Library under Creative Commons permission.

We live in an age when superlatives are often bandied about to describe almost anything, but if any event in the nineteenth century deserves such accolades, it is the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was such a vast and colourful spectacle that some historians suggest that written language simply can’t do it justice. Nevertheless, this article attempts to provide a brief history of the great exhibition, which examines the planning and execution of this wondrous event, as well as the reactions to it and the considerable legacy it left behind.

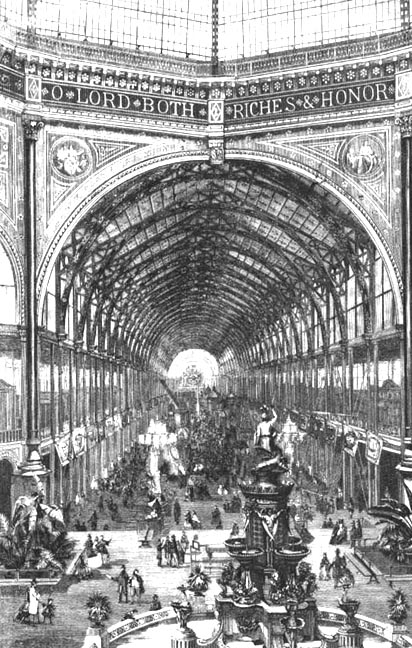

Left: Crystal Palace (1851), East End. Photographer: Henry Fox Talbot. 1851. Right: Fountain at center and view down one aisle Designed by Sir Joseph Paxton.

Background

Historians suggest that we need to understand three important factors that paved the way for the Great Exhibition. These were (1) a liberal shift in politics towards free trade in the 1830s, (2) concerns about expressing British influence in the post-Napoleonic world, and (3) a fortuitous meeting of minds between key individuals: Henry Cole, Prince Albert and Joseph Paxton (Shears 12). Henry Cole, who was the driving force behind the whole project, is arguably one of the most interesting figures of the age. He was a Record Keeper at the Public Record Office, whose lifetime accomplishments included being a painter, author and editor of a manufacturing journal, as well as someone who pioneered the penny post, championed the single gauge railway, designed a tea-set and even invented the Christmas card. In relation to the exhibition, it was his work in industrial design that was key, as he was an active member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (Society of Arts), which is how he came into contact with Prince Albert. The Consort had invented a role for himself by becoming a patron of the arts, which had led to him joining the Society in 1843 and being made its President the following year. Whilst large-scale exhibitions had been pioneered by the French, in 1844 the Society began holding small annual events to showcase useful inventions. The numbers attending steadily increased and in 1849 Cole managed to persuade Albert to hold a much larger national show. The idea was to emulate the vast Paris Exposition, which Cole had visited for ideas, but to make the British version bigger and, unlike the French event, global in its focus. Indeed, it was decided to name it the ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’ (Shears 13).

Motivations

The plan was to stimulate British design and manufacture by promoting innovation and trade, but there were other motivations too. Albert considered the whole project to be a ‘sacred mission’ to help discover God’s laws and conquer nature, thereby increasing reverence for the creator. He also hoped it would promote peace and love amongst the nations. To even consider such an ambitious idea shows something of the spirit of the age, as there was still the major question of how the project would be funded. The solution was to do a deal with a building firm (Messrs Munday), which offered to construct the venue in return for a percentage of the takings. Nevertheless, the agreement included a proviso that the contract could be rescinded if public or private subscriptions could fund it, which is what happened after Cole managed to persuade Albert to request a Royal Commission to take over the organising of the exhibition.

The Commission

The Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. Henry Wyndham Phillips (1820-1868).

After cancelling the contract with Munday, the first job for the Commission, which was made up of prominent politicians and businessmen, was to decide on a site and design for the building. A number of locations were suggested, including Leicester Square and the Isle of Dogs, but Cole’s choice of Hyde Park was eventually agreed upon with a 16-acre plot allocated for it.

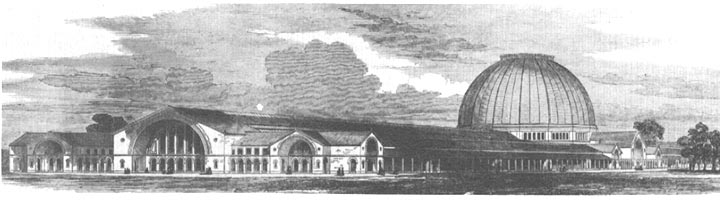

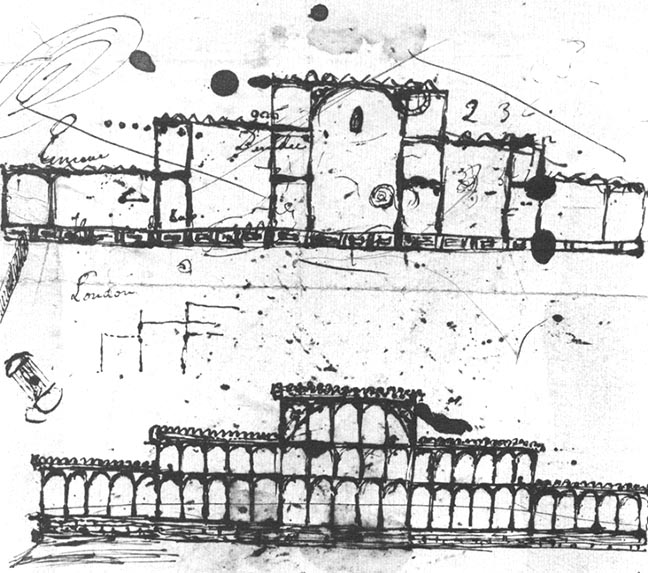

Brunel’s design for the exhibition hall.

Over 230 designs were received by the Commission by its deadline, and although none were particularly liked, a modified version of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s submission was chosen, which was for a brick building with a large dome on top of it. Nevertheless, it proved difficult to find anyone to construct it, because of both the timeframe and the temporary nature of the structure (Beaver, 15-19).

Joseph Paxton

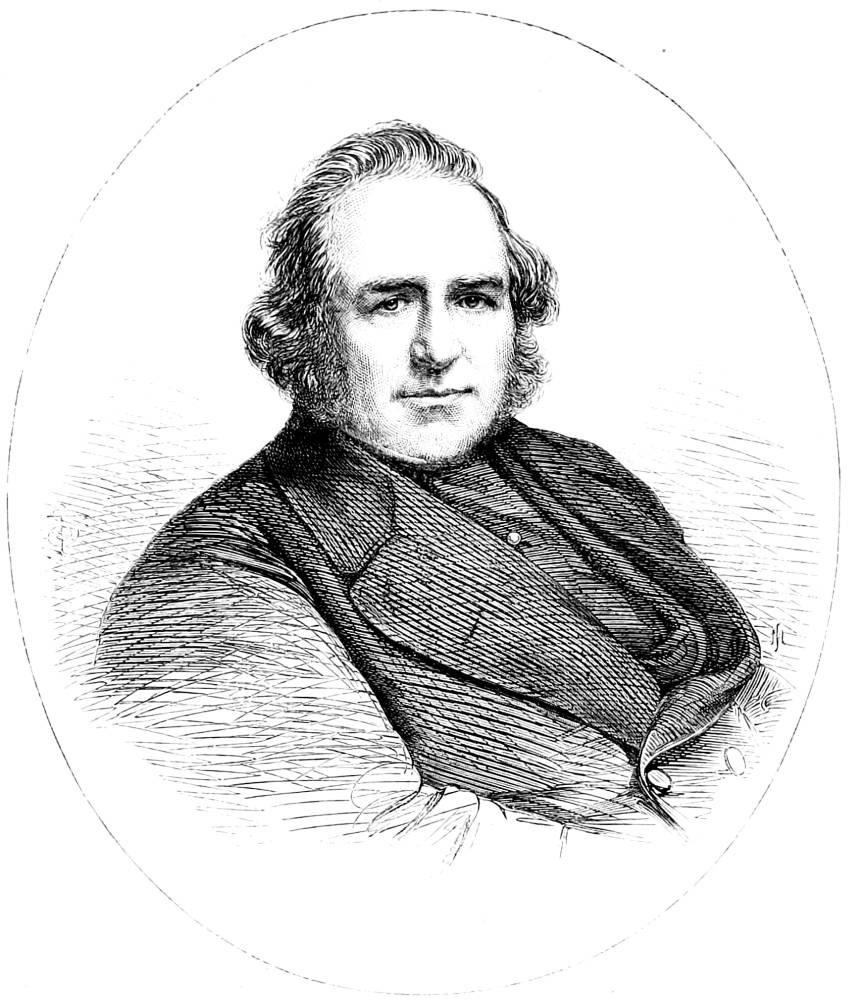

Left: A portrait of Paxton from the 1865 The Illustrated London News. Right: Sir Joseph Paxton's original sketch on blotting paper of the Crystal Palace.

It was another fortuitous meeting – this time involving the Duke of Devonshire’s gardener, Joseph Paxton – that changed the situation. After discussing the building with his friend William Ellis MP, he contacted the Commission and offered to send them an alternative design within 9 days. Two days later, during a Midland Railway meeting, he sketched an idea for a prefabricated iron-framed building with a glass exterior. It was to be a much grander version of the Chatsworth Stove, the largest glass structure in the world, that he had built for the Duke to house some of his plants. Although the revolutionary design constituted a risk, he had had the whole project costed (showing that it was viable) and the Commissioners accepted it. Indeed, Paxton ensured he had to the support of the people by publishing his design in the Illustrated London News, which won the structure a great deal of praise. Punch magazine even called it the ‘Crystal Palace’, which was a name that stuck. The most vocal supporters were those in favour of free trade, some Liberals and certain parts of the press, such as the Daily News (Beaver, 15-19).

The Opposition

Despite its support among many, there was also a sizeable minority, consisting of protectionists, some High Church Anglicans and conservative organs of the press, like The Times, who opposed it. The most vocal spokesperson was Colonel Charles Sibthorp, the 67-year old MP for Lincoln, who had objected to the Library Bill of 1850 on the grounds that he himself had not liked reading.

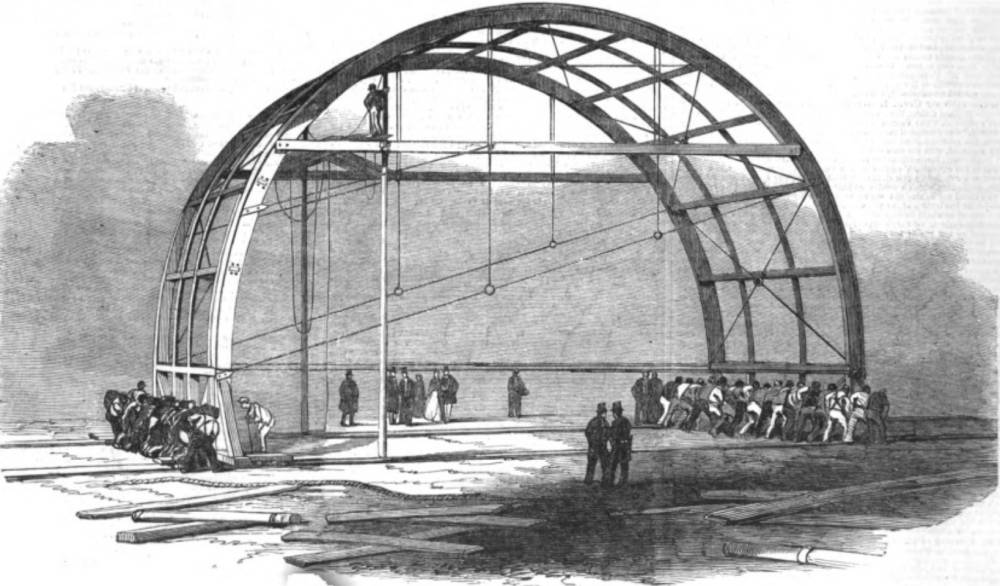

One initial concern was about damage to Hyde Park with Sibthorp being particularly exorcised about the fate of some elm trees that needed to be felled. This particular objection led to the design of the Palace being modified – and arguably improved considerably – as it was decided to add a high arched transept that would enable the trees to remain intact, as a feature within the building. Other worries included the prospect of disruption to the area, the Palace remaining a permanent fixture and the area becoming a hive for criminality. There were also economic concerns about ‘trash and trumpery’ arriving from abroad or that the whole project was a ‘job’ made for commercial profit, even though the Commissioners agreed to a charter that ensured any profits would be reinvested in the arts and sciences. Sibthorp, who told politicians that he was praying for a lightning strike to finish off the Palace, concluded that ‘there has never been a greater humbug, a greater fraud, a greater injustice than this proposed exhibition’ (Beaver, 21-22).

Construction

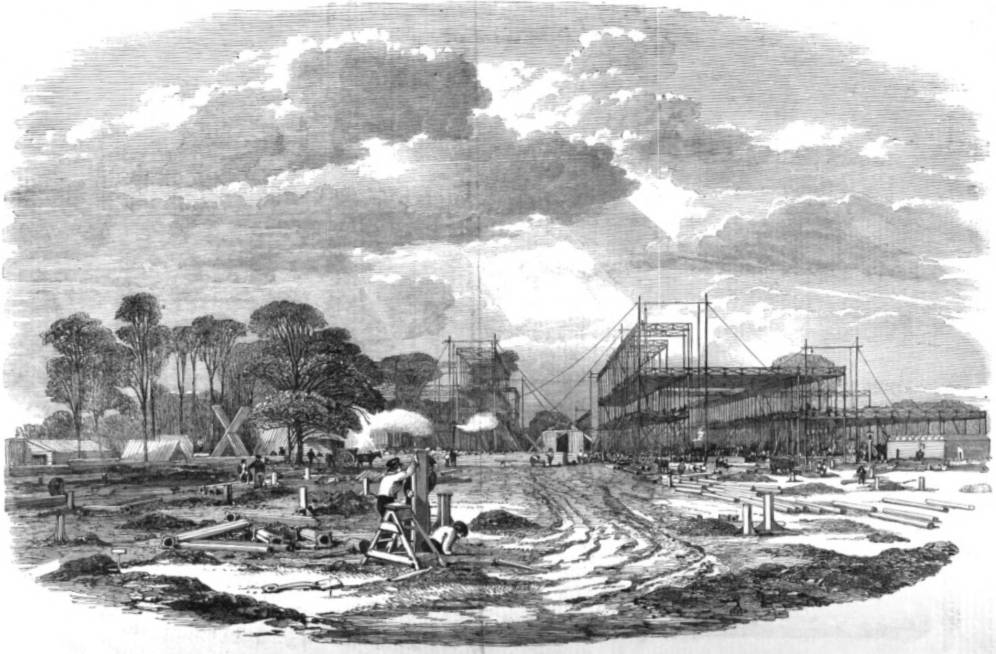

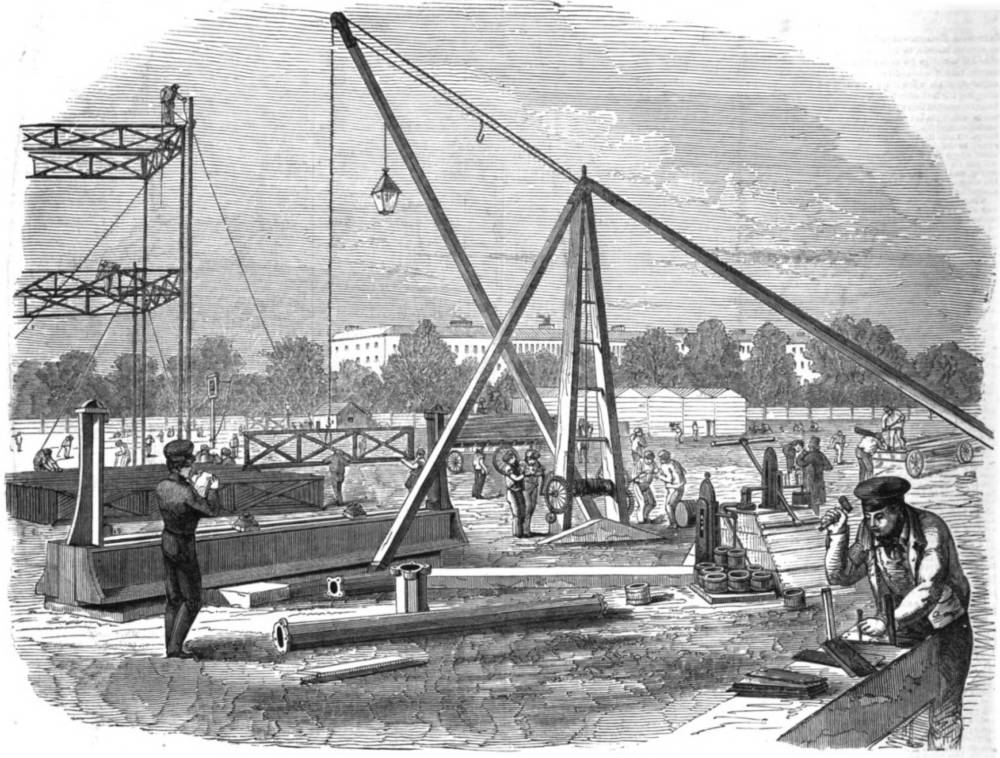

Left: The Building in Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851 — General View of the Works. Right: Pair of Transept Ribs, Framed Together, Previous to Hoisting. Both from The Illustrated London News

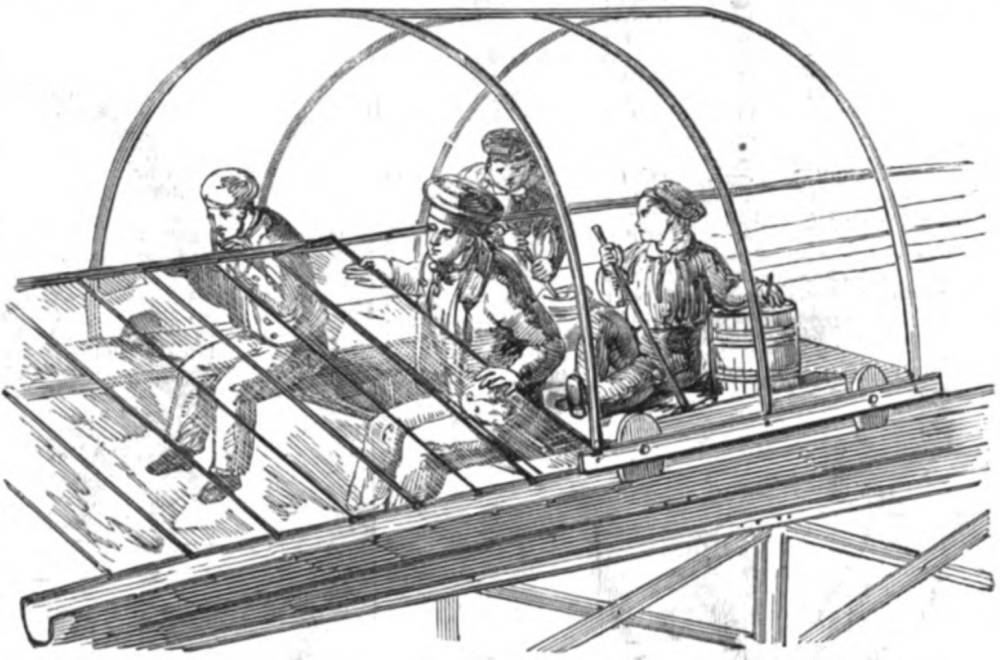

Despite some concerns about whether it would be strong enough, the whole building, which required over 1,000 columns, 2,000 girders, 300,000 panes of glass and over 20 miles of guttering, was constructed in only 22 weeks. This was achieved partly by increasing the workforce from around 40 at the start of the build, to around 2000 by its completion.

Left: Unloading Girders.. Right: Glazing Wagon. Both from The Illustrated London News

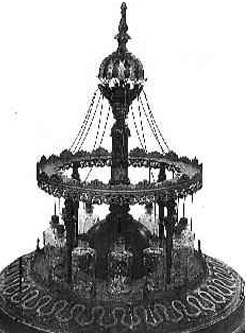

When the Crystal Palace was finally completed it was staggering in its size and beauty. It was not only the largest glass building in the world, but also the biggest enclosed space. It stretched a third of a mile long – three times the length of St Paul’s Cathedral – and it boasted 3 entrances, 17 exit and 10 double staircases. The centre-piece was the glorious fountain, made from 4 tons of pink glass and standing 27ft high (Gibbs-Smith 23).

The Grand Opening

The opening ceremony was held on 1 May and was attended by around half a million people, who congregated outside to watch Charles Spencer taking off in a balloon at 11 o’clock (the official starting time). 25,000 season ticket holders packed the aisles and galleries to witness the royal party arriving at noon to a gun salute, the national anthem, a prayer from the archbishop of Canterbury and a choir singing the hallelujah chorus. One unexpected part of the proceedings was the Queen being addressed by a Chinese Mandarin, who turned out to be an uninvited captain of a junk boat who had been mistaken for a dignitary! Nevertheless, it was a glorious opening ceremony, which Queen Victoria, who was rightly proud of her husband’s tireless work, described as ‘a day to live forever’.

Logistics

The exhibition was not open on a Sunday and smoking, alcohol and dogs were all forbidden. The tickets were initially expensive (£1 for either of the first 2 days and 5s for any of the next 20 days), before reduced prices were introduced to attract different clientele. The cheapest days (1 shilling) were from Monday to Thursday, whilst Friday was more than twice that cost (at 2s 6d) and Saturday was more expensive still (initially at 5s, before being reduced to 2s 6d in August)

There were over 100,000 exhibits on display from nearly 14,000 exhibitors, who had been chosen by various committees. Those presenting had the chance of winning the highest award, the Council Medal, given for innovation (of which 170 were handed out) or the lesser Prize Medal, given for craftsmanship (of which nearly 3000 were handed out).

Although the exhibition was supposed to showcase the works of ‘all nations’ there was an obvious hierarchy, as over half were allocated to Britain. Despite concerns about competition, France was the largest foreign contributor and their sumptuous tapestries, porcelains and furniture won many plaudits (and proportionally a lot of medals). The Zollverein group of German states also brought a large amount, whilst America, Russia and Austria all provided sizeable contributions. By contrast, the Chinese section was quite sparse and not particularly good, whilst some countries only sent a few items and others were not even represented at all.

Exhibits: Britain and the Empire

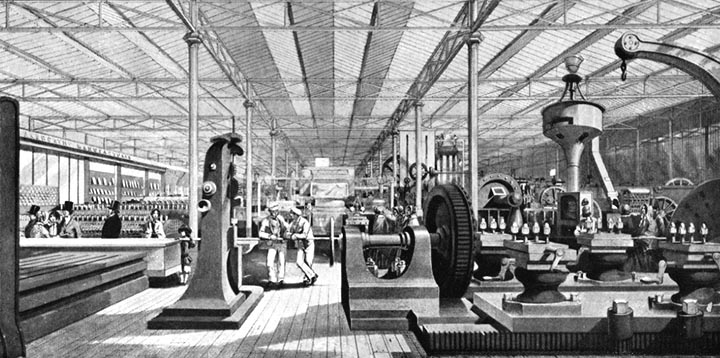

Machinery Section at the Great Exhibition of 1851..

The Britain and the Empire section was divided into four main categories (machinery, raw materials, manufactures and plastic arts) and a further thirty sub-categories. The machine section captured many people’s imaginations because of the cutting edge – not to mention noisy – technology that was on display. The largest exhibits on display were Stevenson’s hydraulic press that had produced many of the huge parts used in the Britannia Bridge at Bangor, and Naysmyth’s steam hammer. There was also a printing machine that could produce 5,000 copies of a newspaper an hour, whilst another that produced envelopes at roughly half that speed. One notable exhibit was the jacquard loom, a weaving machine that used an early form of computing, by creating a pattern dictated by holes punched on a card. There were also many forms of transport on display, ranging from agricultural machinery and locomotives, to carriages and velocipedes (the precursor to the bicycle). Many smaller items were shown too, including an early facsimile machine and photographic equipment. Indeed, some early daggeureotype photographs of the moon, taken at Harvard Observatory, captured the imaginations of many people, as did the large British-built Trophy Telescope that loomed over many of the smaller exhibits.

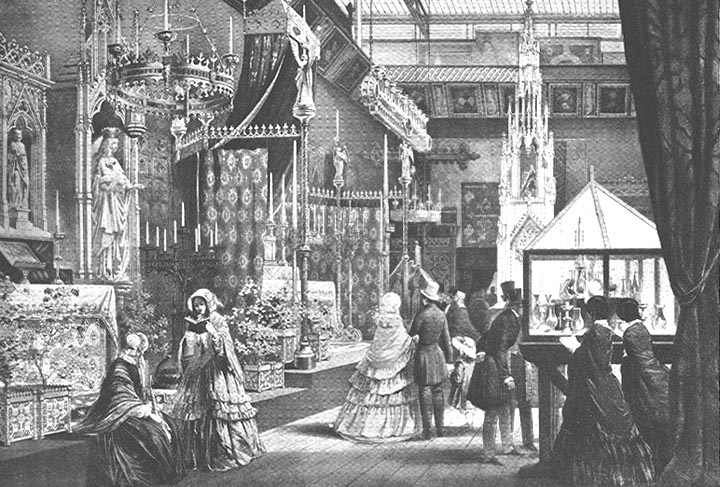

Left: Indian Art Objects displayed at the Great Exhibition. Right: Pugin’s The Medieval Court at.

Yet the displays weren’t all about the onslaught of modernity. Augustus Pugin’s medieval court harked back to an earlier age, although, at a time of heightened religious tensions, many complained about the religious statutes appearing to promote popery. Similarly, the raw materials section was less technologically advanced, as it contained obelisks, anchors and lumps of coal.

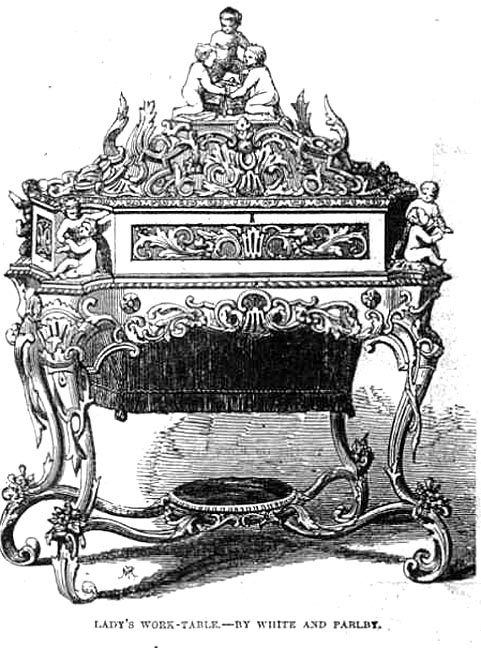

Some areas were inevitably more colourful than others, such as the stained glass windows section (with light streaming in), the carpets on display from Axminster and the ribbons from Coventry. The jewellery section was also popular and pride of place was given to the famous Koh-i-noor diamond, said to be the largest in the world and of inestimable worth. Unfortunately, it did not sparkle well, which is one reason why it was subsequently recut and placed into the Crown Jewels. Other rare jewellery included the Daria-i-noor, a rare pink diamond, and the 8th century Tara Brooch that had been discovered in Ireland the year before. There was a great deal of artwork on display that added to the aesthetic appeal of the exhibition and Augustus Kiss’ ‘Amazon’, showing a rider being attacked by a tiger, was a particularly popular item. Furthermore, there were many more items that were exquisite decorative masterpieces, even though they were not officially classed as art, such as some of the ornate furniture on display. There were also some highly unusual offerings, including an expanding coffin, a miniature working colliery, waterproof paper, self-suspending trousers, a defensive umbrella (with a sharp end to ward off attackers), a knife with 1851 blades, a silent alarm bed that tipped the sleeper onto the floor at a predetermined hour, and an electric telegraph where a face appeared to speak the words shown above it. Those aimed at helping the disabled, included a pulpit with gutta-percha tubes running to the pews for the deaf to hear, writing ink that was raised for the blind to feel, a walking stick with space inside for medicines and surgical instruments, and even a false nose made of silver. Others were unusual, because of the materials they were produced from, such as a vase made out of mutton fat, a hat made by Australian prisoners out of the cabbage-tree, and cuffs knitted from the fur of French poodles!

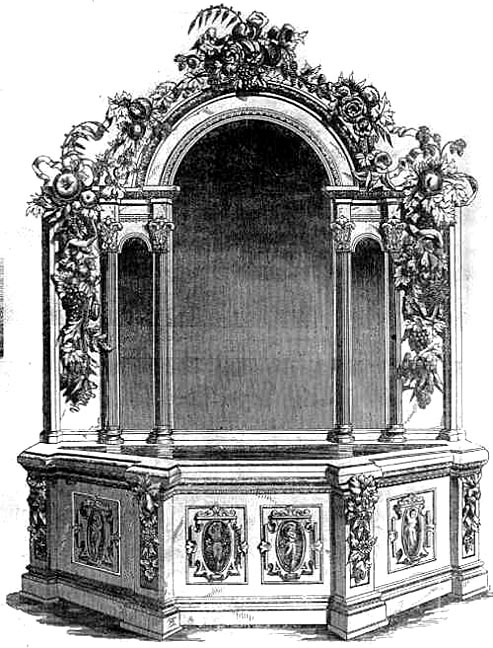

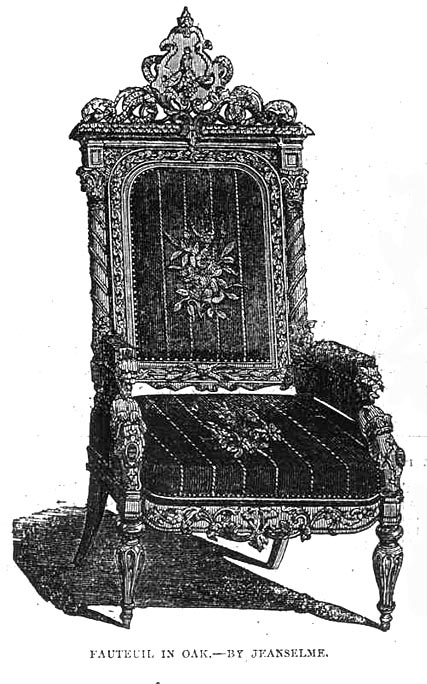

Lady's Work Table, Sideboard, Fauteuil [Chair], and Flower Vase in Gothic Style.

One of the most bizarre displays, which Victoria described as ‘really marvellous’, was a whole assortment of stuffed animals recreating everyday scenes produced by Plocquet of Wurtenberg, including a frog shaving another.

Dr. George Merryweather’s 1851 Tempest Prognosticator

Another highly unusual item was the ‘tempest prognosticator’, an instrument produced by the aptly named Dr Merryweather. The machine, which was rather optimistically hailed as ‘one of the grandest ideas that ever emanated from the mind of man’, contained a number of leeches that were connected to a bell, so that their movement would warn the owner of inclement weather.

The public toilets, the first of their kind, also caused a stir, even though they were not supposed to be an exhibit. 800,000 visitors took the opportunity to ‘spend a penny’ (an expression that originated from the exhibition) and use the retiring rooms designed by George Jennings, which featuring flushing toilets (Beaver 47-63, Leapman 165-190).

Ticket sales

The overall ticket sales show what an incredible success the exhibition was, as over 6 million visitors attended it – although this figure included those who attended more than once – at a time when the country’s overall population was only 27 million. The highest single attendance of any day was 103,000, which was recorded on 7 October.

| Season (£3 3s/£2 2s): | 773,776 |

| £1 days (2 days): | 1,042 |

| 5s days (28 days): | 245,389 |

| 2s 6d days (30 days): | 579,579 |

| 1s days (80 days): | 4,439,419 |

| Total: | 6,039,195 (Gibbs-Smith 24) |

The large numbers were helped by travel companies providing heavily discounted train tickets, as well as – in an age before statutory paid holidays – some benign employers giving their workforce time off and sometimes paying for them to attend.

We also know that many came from abroad, as an official report suggested that three times as many people entered the country during the exhibition period, as had done the previous year, with the most coming from France (27,000), the German states (10,000) and the United States (5,000) (Shears 95). The influx of people inevitably helped businesses providing transport, accommodation and other services in the area, whilst those in many other parts of London complained that they suffered from so much trade heading to Hyde Park. Unsurprisingly, the large crowds also consumed a great deal. Messrs Schweppes, who had paid £5,000 to run the four designated refreshment rooms, sold over a million bottles of soft drinks and almost as many Bath buns. Nearly 300,000 gallons of filtered water (provided free of charge) was pumped from 2 miles away by the Chelsea Waterworks Company, whilst 270 gallons of eau de cologne and other scents was distributed duty free, as was over 500lb of snuff, 250lb of tobacco and as much as 480lb of chocolate (from the Saxon division alone) (Gibbs-Smith 24).

Reactions

As the visitor numbers suggest, the vast majority of visitors appeared to have greatly enjoyed the spectacle of it all, such as W. M. Thackeray who enthused that the ‘the eye is dazzled, the brain is feverous’. A few found it all too much, however, like Charles Dickens who claimed he was ‘used up’ by the experience, as the ‘natural horror’ of the sights led him to conclude that he wasn’t sure if he had seen anything, except the amazon statute and the fountain!

Some groups had more of a mixed response. Whilst some religious commentators claimed the exhibition showed the fruits of Christianity or inspired worship of the creation (as Albert had wanted), others saw it as a modern day ‘Feast of Belshazzar’, i.e. worshipping the material rather than God. Some complained about the aesthetics of the whole affair. William Morris described the exhibition as ‘wonderfully ugly’, whilst John Ruskin and A.W.N. Pugin both strongly preferred traditional architecture.

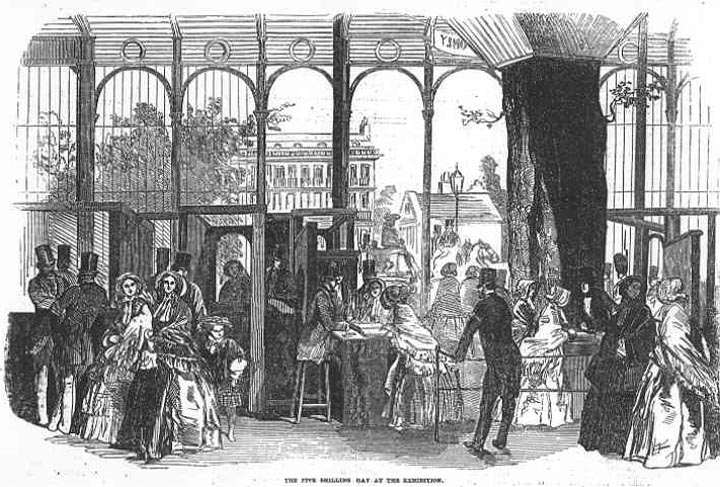

With Chartist demonstrations sweeping the country and social unrest affecting many parts of Europe, it is unsurprising that class tensions were simmering under the surface. Many newspapers expressed concerns about the working class and a number of them compared the clientele on different days. The Times noted that once the ‘aristocratic element retired… king mob enters’, whilst the Illustrated London News contrasted the ‘day of the great folks’, for those from the west end of London, and the ‘day of the little folks’, for those from the rest of the world. Some cartoons depicted the exhibition as being like a zoo, where people could view the visitors inside, including those in their vocational clothing.

Left: Agriculturalists at the Exhibition. Right: The Five Shilling Day at the Exhibition .

The mixing of the sexes was also a considerable concern for many, as well as an attraction for some. Women were highly visible in an exhibition that had items marketed at both sexes, even though the prevailing ideal of the time was moving towards the two operating in separate spheres. The Times noted that an attractive lady in the newly fashionable bloomer attire attracted “no small share of attention”, whilst the fisherwoman, Mary Callinac, gained notoriety not only for attending the exhibition with a fish basket on her head, but for the fact that she had walked there from Cornwall. There were also concerns about respectable women rubbing shoulders with high class prostitutes, as well as worries about overcrowding, fainting and hysteria.

Whilst the exhibition helped to heighten British patriotism, it also drew to the surface negative attitudes towards other nations, some of which bordered on xenophobia. The Times noted, for example, that the ‘the bearded faces’ of foreigners conjured up ‘all the horrors of free trade”. Similarly, Colonel Sibthorp, who refused to attend the exhibition, claimed that the ‘big bauble’ had only benefited foreigners and contractors, whilst the British public had been ‘trepanned, seduced, ensnared and humbugged out of their hard earnings’ by all the ‘foreign fancy rubbish’ (Shears 77-185, Gibbs-Smith, 21-22).

Legacy

Although some hoped that the Palace would remain open, including Cole who wanted it turned into a vast winter garden full of plant life, the closing ceremony for the exhibition was held, as planned, on 15 October. Yet whilst most commentators are in agreement that the whole event was a great success, it is harder to pin down exactly what its lasting impact was.

Besides changing the topography of London, it helped to shape people’s tastes for the spectacular and certainly inspired many further exhibitions. It definitely didn’t bring about world peace, although it probably accelerated the acceptance of free trade. It also undoubtedly inspired some innovation, as well as helping to normalise the machine. Indeed, it arguably ushered in a new age of consumerism, in which advertising became much more accepted, as well as having a major impact in shaping excursion and holiday trends. Furthermore, it even launched the America’s Cup, which started as a one-off race around the Isle of Wight during the exhibition.

The event also made an enormous profit (approximately £180,000) and one of the most far-sighted plans of the organisers was the reinvestment of the funds in purchasing nearly 90 acres of South Kensington. The area, nicknamed ‘Albertopolis’, was used as a site for various museums to house the exhibits, as well as colleges to promote science and the arts. Those build on the plot included the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Natural History and Science Museums, Imperial College, The Royal College of Music and the Royal Albert Hall (outside of which a statue of Albert was erected to commemorate his role in the great exhibition). Furthermore, the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 funded (and continues to fund) many postgraduate students who went on to make considerable contributions to the field of science and the arts (Shears 186-228).

Later developments. Left: Natural History Museum. Middle: Victoria and Albert Museum. Right: The Royal Albert Hall (.

Sydenham

The end of the exhibition was not the end of the Palace, however, as the building was bought by a new consortium who reconstructed it in a modified form, which included two distinctive water-towers designed by Brunel. Perhaps the most unusual group to accompany the relocation was a collection of model dinosaurs that were commissioned from Benjamin Hawkins to go by the lakes in the newly renovated grounds.

The Dinosaur Court, Crystal Palace Park. Penge (Sydenham Hill), south-east London.. The prehistoric creatures modelled by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. 1852-54; restored 2001-03.

The scientific knowledge of their anatomy was only just developing at the time and whilst some of the models turned out to be relatively accurate, others certainly were not.

Like its predecessor, the Palace was filled with many interesting artefacts and it attracted an annual average of 2 million visitors per year. It became renowned as a venue for lots of major events, from musical festivals, dog shows and fireworks displays to balloon ascents and sporting contests. Furthermore, many other attractions were built in the park over the years, including a maze, aquarium, miniature railway, fairground rides, cinema, racing track, boating lake and various sporting facilities.

Although the building survived a small fire of 1866, the Palace was almost completely razed to the ground on 20 November 1936, despite many of London’s fire brigades trying to tackle the blaze. Afterwards one commentator lamented that ‘we were at the highest of our glory in 1851 – where are we today? Let us hope the disappearance of the palace may not be an omen’. Some believed it was, as within a fortnight the King had abdicated and the continent was already spiralling towards the Second World War, which would transform Britain forever (Beaver 141-48).

Conclusion

Given the sheer variety and magnitude of the Great Exhibition of 1851, it is unsurprising that historians have saturated it with so much meaning. Indeed, it was undoubtedly one of the outstanding success stories of the nineteenth century, from which you can study almost any aspect of Victorian culture. One commentator poignantly summed it up, by saying ‘everywhere anarchy, repression, conspiracy, darkness, dismay and death. In the midst of all these struggling spirits rises up the great figure of the Crystal Palace, to redeem the age’ (Athenaeum 18 October 1851).

Although there have been occasional plans to resurrect it, the Crystal Palace was never rebuilt. Its memory is perpetuated by a small museum in the park and if you look carefully around it you can still see glimpses of its former glory, including the grand terraces flanked by sphinxes, the dinosaurs lurking by the water, and the giant bust of Joseph Paxton still watching over the site. A final interesting postscript is that John Logie Baird conducted many of his early experiments on the television from within the Sydenham Crystal Palace. Indeed, it is perhaps fitting that out of this grand museum of innovation came one of the most revolutionary pieces of technology of the modern age that would itself launch a whole new type of spectacle (Beaver 148-49).

Related Material

Bibliography with Suggestions for Additional Reading

Beaver, Patrick. The Crystal Palace. Phillimore and Co, 2001.

Colquhoun, Kate. "The Busiest Man in England:" A Life of Joseph Paxton, Gardener, Architect, and Visionary. Boston: David R. Godine, 2006. [Review by George P. Landow]

Gibbs-Smith, C.H. The Great Exhibition of 1851. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1981.

Leapman, M. The World for a Shilling. Headline, 2001.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. High Victorian Dessign: A Study of the Exhibits of 1851. London: Architectural Press, 1951.

Shears, Jonathan (ed.). The Great Exhibition, 1851: A Sourcebook. Manchester UP, 2017.

Related Websites

“Building the Museum.” The Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 28 April 2020.

Picard, Liza. “The Great Exhibition.” British Library/ 14 Oct 2009. Web. 28 April 2020.

Created 28 April 2020

Last modified 18 February 2025