Prior to 1832 the only people who could vote in General Elections in the United Kingdom were men who owned freehold property that was worth over 40 shillings. On rare occasions women could also cast a vote at general elections in the eighteenth century (at times when, for example, her property-owning husband was absent on business; some borough franchises also accorded the right to vote to people, irrespective of their sex, simply because they met the property and rate-paying qualifications). While the property qualification was fairly low in terms of its affordability, very few people owned freehold property. The majority of the population in Britain being renters or tenants-at-will, or even living on manorial lets that their families had occupied since time immemorial, meant that the franchise was limited to a very small number of the adult population.

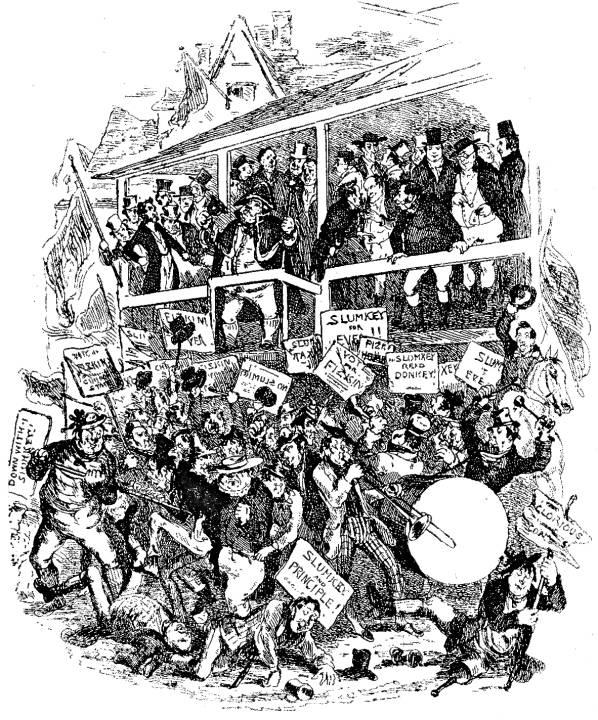

The Successful candidate. Phiz. The Illustrated London News. (24 July 1852): 57. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

When people went to the polling stations in the eighteenth century, they voted in the constituency where their property was based. For example, the antiquary Joseph Ritson (1752–1803), although he lived in London, had to travel back to his home town of Stockton-on-Tees to cast a vote because that was where his property was situated. And when people cast their ballots, they did so for MPs to represent them at a county or borough level, and each of these returned two MPs.

The first and second parts of William Hogarth's The Election: Humours of an Election Entertainment and Canvassing for Votes .

However, many of the up-and-coming manufacturing towns and cities such as Leeds and Manchester were not represented at all in parliament. Some boroughs like Old Sarum, which was nothing but a virtually uninhabited hill with a cottage in the early nineteenth century, meanwhile returned two MPs to parliament. Boroughs such as these were nicknamed ‘rotten boroughs’ for obvious reasons. It seemed as though the electoral system was not fit for purpose—and many agreed.

The coming of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815)—the ‘first’ world war in many respects—saw the voices of the increasingly influential middle classes combine with the working classes to call for reform of the political system and extension of the franchise. As a result of a long campaign for parliamentary reform during which the middle and working classes campaigned for universal suffrage. The government decided it was prudent to give the vote to some more people. The result was the Reform Act of 1832. From now on the franchise was extended to people who owned freehold property worth over 40s; people who owned copyhold property worth over £10, which was land held by a manorial tenant which could not be passed on to a family member after a person’s death but reverted back to the manorial lord; and male householders who paid rent on any property worth over £50 per year.

Left: The Election at Eatanswill. Illustration of Dickens’s Pickwick Papersby Phiz. Right: Electoral Purity in the 1866 Fun. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The constituency map was also redrawn: towns such as Manchester were enfranchised while some boroughs like Old Sarum lost representation. As a result of the Reform Act, 401 constituencies were created. Although there was 401 constituencies, upwards of 650 MPs were returned to parliament. Some constituencies were redesigned so that they only returned one MP to parliament. However, larger boroughs after 1832 still returned two MPs. So when a person received voting rights, he—and the 1832 Act specifically specified men, leading to women’s complete disenfranchisement—still received the right to cast two votes at elections. Under this system, if a voter wanted to support only one party, he could opt for a ‘straight-party vote’ and cast his votes for the two candidates who had been nominated by a single party. If a voter could not decide which party to vote for, he might even cast one vote for the Tory candidate and one vote for the Whig candidate. This was called ‘splitting’ the vote (Phillips and Wetherell 300) The franchise qualifications and voting rights may sound complicated and, well, they were! But how did this work in practice? Who drew up the electoral registers? How much, if any, fraud was committed at election times?

The process for registering voters across the country was not uniform across the country. In borough constituencies, the town clerk was responsible for drawing up the electoral register. He did this by collating lists of local rate payers with the roll of freemen and burgesses. The people responsible for drawing up lists of electors in county constituencies was the parish overseer. All people who felt that they were entitled to be able to vote in elections had to write to the parish overseer, tell him that they possessed the necessary property-owning or rental qualifications, and his name would be entered onto the register (Thomas 82).

According to J.A. Thomas, “such was the pattern of the registration system set up by the acts of 1832 and 1867. In neither county nor borough was it an automatic system. In both it made demands upon the initiative of the person already qualified to exercise the franchise” (Thomas 83). Yet overseers were merely men, prone to mistakes, and sometimes they couldn’t be bothered keeping the electoral register up to date. Some overseers, complained the barrister John David Chambers in The New Bills for the Registration of Electors Critically Examined (1836), were wholly illiterate (Thomas 85). There seems to have been very little means of effectively checking whether a person’s freehold property was worth £2, or whether they were £10 leaseholders. Thus, as Thomas further argues, it was entirely possible, and indeed it very often transpired, that people who were not entitled to vote managed to get on to the register with, barring any objectors, little or no hassle.

If this sounds too easy, however, there was a catch: the register of electors had to be displayed publicly and if someone—anyone—felt that you were lying, they could challenge your right to vote. An investigation would be launched by a Revising Barrister. These guys would then be tasked with assessing the potential voters’ right to vote. If the objection turned out to be frivolous, then, on the recommendation of the revising barrister, the person making the objection could be sued for damages.

Little is known about the Revising Barristers. As Ann Hale told me in an email to the Victoria List, their role

Is in need of greater scholarly attention. It was an important position for underemployed barristers, which is why I became interested in it. However, I haven’t come across much work on the subject other than Hansard coverage and a variety of nineteenth-century articles and cases about the role.

The fact that it was a duty undertaken by barristers when they were feeling the pinch of poverty probably explains why there was no formal association for revising barristers. And it was good work if they could get it. They earnt 5 guineas (£5 5s) and expenses for their time (“The New Reform Bill” 3). Following on from what Hale says, it seems, from a brief glance at newspaper archives, that the investigations of the Revising Barristers were reported on in the press. The Sheffield Independent report on 19 September 1874 is fairly typical:

IMPORTANT DECISION OF A REVISING BARRISTER The revising barrister at Lambeth has decided that an inmate of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association Houses who does not pay rates is not entitled to vote. [“Important Decision” 1].

To assess whether someone was truly eligible to vote, an interview with all concerned parties—the would-be voter, the objector, representatives of each political party, and the parish overseer—was held in the Town Hall. The press was also present on these occasions to report on the revising barrister’s ruling (“Amiable Revising Barrister” 5). One newspaper article from later in the century goes into a bit more detail in covering the proceedings of these public meetings. In this extract William Fryer’s right to vote is challenged not on financial grounds but on the matter of where he resided—a requirement of the Reform Act being that one had to be resident in the constituency where you intended to vote.

William Roles Fryer, on the list as the freehold owner of Lytchett Minster, Dorset, was objected to by the Conservatives on the ground that this was not his address.—Mr Millar Darling asked the overseer if his address was correct, and he replied that he did not know.—Mr Gosling asked for some evidence of a change of address.—Mr Brown said that he had made inquiries and found Mr Fryer left Lytchett some nine months ago, having sold the place to Mr Lees M.P.—Mr Fryer was now residing at Verwood, and had been there since the middle of July. Mr Gosling asked for proof of the change of address and the exact date.—Mr Brown said he had left about the 8th of July.—The Revising Barrister said it was so very near that he must have the correct date. If he was there till the 15th of July then his claim was good.—Mr Brown could not state the date of leaving Lytchett, but said Mr Fryer took possession of the other house on the 8th of July. The Barrister decided to disallow the objection. [“The Revising Barrister at Fordingbridge” 6]

While the proceedings of the Revising Barrister’s interviews make for very dry reading (doubtless more will have been said at these meetings and the journalists condensed the proceedings), they represent a good attempt to preserve the integrity of the electoral franchise—limited though it was in the nineteenth century.

But was there ever a time when a constituency election result was put to a re-count because of the people who voted weren’t actually allowed to vote?

The General Election of 1841

Results of the 1841 Election

This brings us to the General Election of 1841. It was a contest between two giants of the early Victorian political scene: Lord Melbourne (Whig) and Sir Robert Peel (Conservative). The result is well known: Peel won what we might call a ‘landslide’ with 367 Conservative MPs returned to the Commons, while only 271 Whigs were returned. The Whig candidate for Lyme Regis, William Pinney, thought he was at least safe by keeping his seat. The Tory candidate, Thomas Hussey, however, thought this was most unusual. Hussey petitioned for a recount. An inquiry was held locally. Several parish overseers and voters were hauled in front of a committee of Revising Barristers. The former group had their competence called into question and the latter group’s eligibility to vote was queried.

The vote of William Bazley, who supported the Whig candidate, was struck off for several reasons: Bazley claimed to rent property but it could not be proved that he paid over £10 per annum and upon investigation it was concluded that the property through which he claimed his eligibility to vote was in fact being rented by someone else up to a year before the election. Thus, “The Chairman stated that the Committee were of the opinion that the vote of William Bazley was a bad vote and must be struck off the poll” (“Minutes of Proceedings” 39). Another man, named James Hiscott, also had his vote struck off the poll. It appears that Hinscott claimed to rent a house with a shop attached to it. Taken together, these properties took him over the property qualification and also satisfied the residency requirement. Yet upon investigation it transpired that Hinscott merely rented the shop and lodged somewhere else in the town, thus disqualifying him. William Hicks’s vote was suspect on the fact that his property was been grossly overvalued. Before the election, the register listed Hicks as a man who paid £11 in rent per annum and liable to pay £7 in taxes to the local authority. Yet when the Hicks’s finances were investigated, it transpired that he was actually renting a different property and paying £3 10s. The property he had originally listed had actually burnt down

Bazley, Hicks, and Hinscott were not atypical. Many people voted who voted in that constituency during the 1841 election should not have done so. The result of the extensive investigation into the Lyme Regis election was that the Whig candidate’s election win was declared void and, one year later, Hussey was announced as the Tory MP for Lyme Regis.

Bibliography

‘An Amiable Revising Barrister’, Birmingham Daily Post (20 October 1864): 5.

‘Constituencies and Elections’, in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons, 1690-1715. Ed. D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, and S. Handley, accessed 10 April 2020. Available at: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org.

Hale, Ann M. Personal Communication [Email], 22 March 2020.

Heater, Derek, Citizenship in Britain: A History. Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

‘Important Decision of a Revising Barrister’, Sheffield Independent (19 September 1874): 1.

Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence Taken before the Select Committee on the Lyme Regis Borough Election Petition. London: House of Commons, 1842.

‘The New Reform Bill’. Lancaster Gazette (24 December 1831): 3.

Phillips, J.A. The Great Reform Bill in the Boroughs: English Electoral Behaviour 1818-41. Oxford University Press, 1992.

———. and C. Wetherell, ‘The Great Reform Act of 1832 and the political modernisation of England’, American Historical Review 100 (1995): 411–36.

‘The Revising Barrister at Fordingbridge’, Southampton Herald (11 October 1890): 6.

Ritson, Joseph, Letters of Joseph Ritson. Ed. Joseph Frank. 2 vols. London: William Pickering, 1833.

Thomas, J. Alun, ‘The System of Registration and the Development of Party Organisation, 1832-1870’, History 24: 123/124 (1950): 81-98.

Last modified 20 May 2020