Excerpted, adapted and formatted for this website by Jacqueline Banerjee, together with the original illustrations.

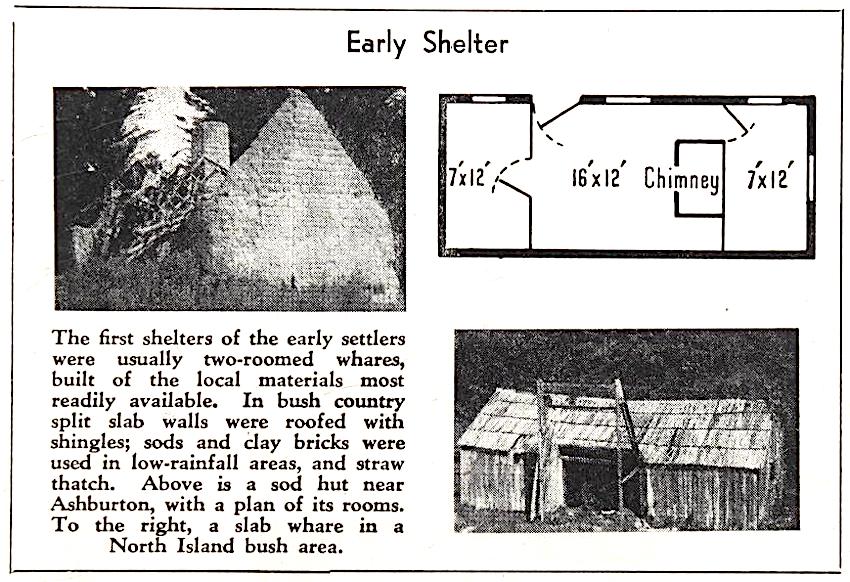

The First Shelters

Lack of stone was one of the first difficulties encountered by the New Zealand colonists, and there are frequent accounts in pioneering reminiscences of "huts built with the aid of friendly Natives," and using, naturally, the materials of which the Maoris made their own whares. European customs, however, demanded some modification of design, to allow for interior partitions and more height, space, and light. The following account, dated 1840, is typical:—

On arrival we found temporary shelter in a tent made of ship's sails, divided into sections by piling up boxes and hanging blankets. Here we had to sit for days with umbrellas up to keep off the rain. Later a wattle and daub hut wes built with the aid of friendly Natives. This hut was of the usual type erected by the first settlers. The walls were of flax leaf and toi-toi laced in and out of a framework of saplings and then daubed with clay. Jue fireplace was of stones, the chimney of supplejack plastered with clay. Windows were of calico or wooden shingles, with flax mats to cover the floors. The scanty furniture was contrived out of boxes. When her husband apologised for the shortcomings of this whare, the woman whose home it was to be reassured him, saying, "What more do I want? I can walk about in it without bending. I can cook inside if required."*

Other materials used in these whares were wheat straw, tree ferns plastered with mud, raupo, and totara bark.

The period of fusion of Maori and pakeha design was, however, brief. The whares were regarded as purely makeshift by most of the settlers, and it was not long before the abundant timber resources of the country were utilised and houses of pit-sawn boards or split logs erected, usually two rooms with a wide, open hearth. These [357/359] were often added to later, and, as the first dwelling for a farm in the making, the type has persisted.

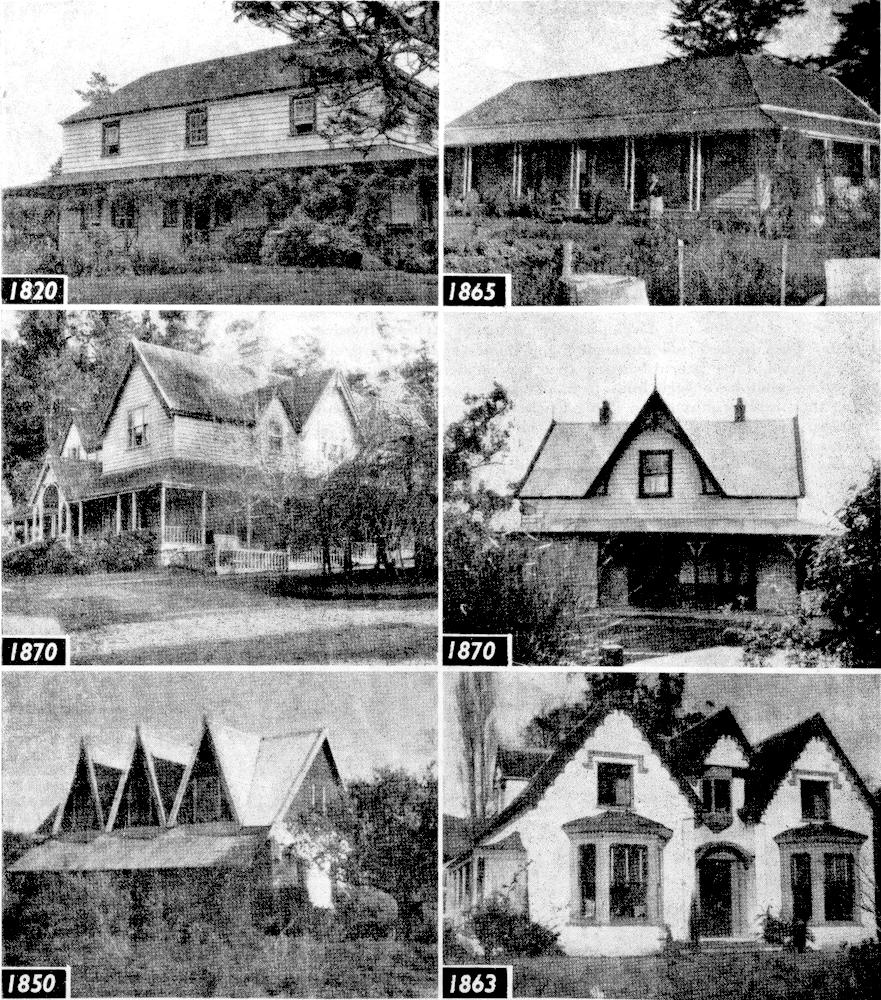

These are homesteads built before 1870. In every case but one corrugated iron roofing has replaced original tiles, shingles, or slates. The simplicity of early design, well-proportioned and based on straight lines, is llustrated in the first two examples, and a very large proportion of the early homesteads were of this type. The two-storeyed building erected in 1820 was the first wooden house in New Zealand. The steeply-pitched gabled roofs and ornamental details are typical of a slightly later period. Most of these early homes were built of wood, but a few were of stone or clay. [358/359]

In some areas, Canterbury particularly, lack of timber caused the development of sod and cob houses, which made use of the only plentiful materials, the earth and the native grasses. Rectangular sods were cut and used as bricks, bonded together with a "mortar" of earth and water, for the building of walls. The roof was a wooden framework thatched with tussock, snowgrass, or reeds. The walls were smoothed inside and whitewashed, and the earthen floor tramped hard. For cob houses the earth was puddled with water and the mixture packed into a wooden boxing, which was afterwards removed, leaving solid walls; or moulded into large bricks which were left to dry in the sun and then built up into walls, again cemented with mud. A proportion of chopped tussock or flax was sometimes added to the cob mixture. A further variation was the "slab, cob, and ricker" construction — the space between an outer wall of timber slabs and an inner lining of saplings was filled with cob.

As with the whares there was a typical plan, a main room which had a door in the centre of one wall, with a window on either side of it; and a huge cob chimney with an open hearth taking up most of another wall. Opening from this room were smaller apartments, sometimes arranged in a straight line, sometimes at right angles or as lean-tos. In some of the larger houses of this type an attic was built under the roof for extra sleeping or storage space, with a ladder or staircase from one of the lower rooms leading up to it.

A few settlers brought wooden houses with them, complete with panes of glass for the windows, and bricks for the chimney. It was supposed to be possible to erect these in a few days, but several complaints are recorded that weeks rather than days were required.

The Homesteads

After the earliest pioneering days more substantial homes appeared. In some cases the settlers were able to build fine homes soon after their arrival; in most the transition from hut to homestead was more gradual, keeping pace with the expanding size of the family and the progress of their fortunes. These early homesteads, built by the wealthier settlers and carrying on so far as was possible in a sparsely-settled country the traditions of English country houses, possessed many pleasing features. They were well and soundly built, some few from brick and stone, but the majority from wide weather-boards with shingle or tile roofs, later replaced by corrugated iron. In exterior appearance and interior finish they maintained high standards of crafts manship and good design. The sites were chosen with care, particularly in relation to sun and view, and gardens were planned to form an appropriate setting for the house. One unfortunate feature, however, was that many of the trees planted for shade and shelter grew, in New Zealand's milder climate, much more rapidly and much larger than was expected, so that they tended to crowd in upon the houses, making them damp and gloomy even in summer, and constituting a real danger in gales and thunderstorms.

Such houses were large — l2 to 20 rooms being usual for the two-storeyed types and up to 10 for the one-storeyed. In addition, there were often attics and outbuildings of various kinds, while wide front halls, folding doors between rooms, and verandahs connected to the living rooms with french doors increased the space available for living and particularly entertaining. Indeed, it was not uncommon to have one room large enough for, and known as, a "ballroom." All the rooms were large by present-day standards — bedrooms 16ft. square, living rooms 20ft. x 24ft., and the big kitchen was usually supplemented by a scullery almost as big, and one or more pantries which were rooms in themselves. The height of these rooms — a 10ft. to 12ft. stud — and their many windows added to their air of spaciousness. Wide verandahs extended along two or three sides of most houses, but balconies upstairs were not so common. In addition to a back, front, and sometimes a side entrance opening into passages, many rooms had french doors which opened directly outside or on to the verandahs.

Many of the larger two-storeyed houses had two or even three staircases. The main stairs, usually one long straight flight, led from the front hall to the main rooms above; the back stairs — darker, narrower, and often twisted — opened from a back passage or kitchen; and gave access to back bedrooms or attics. Occasionally, in accordance with the English tradition, the back premises — kitchen, scullery, storerooms, and servants' quarters — were shut off from the rest of the house by heavy doors or a long passage.

Indeed this relegation of the kitchen and working areas to the back of the house, almost invariably the south side, and so cold and sunless, was the chief defect in the planning of these homes. This was accepted in an age when domestic work was regarded as something rather degrading, to be performed by servants and hidden as far as possible, but this is no longer the case. Under modern conditions it is the homemaker herself who spends most of her time in the kitchen, which frequently is also the meal- room and part-time living room for the whole family. In the same way the very large kitchen and adjoining service rooms, which provided necessary space for several workers, mean merely extra and unnecessary steps for someone working alone. Lack of [359/360] domestic help, smaller families, high building costs, and other factors make very large houses impracticable or undesirable under modern conditions, but there are many characteristics of these early styles which we could retain with advantage, and the one-storeyed and smaller two-storeyed types need little modification to make them conform to modern standards.

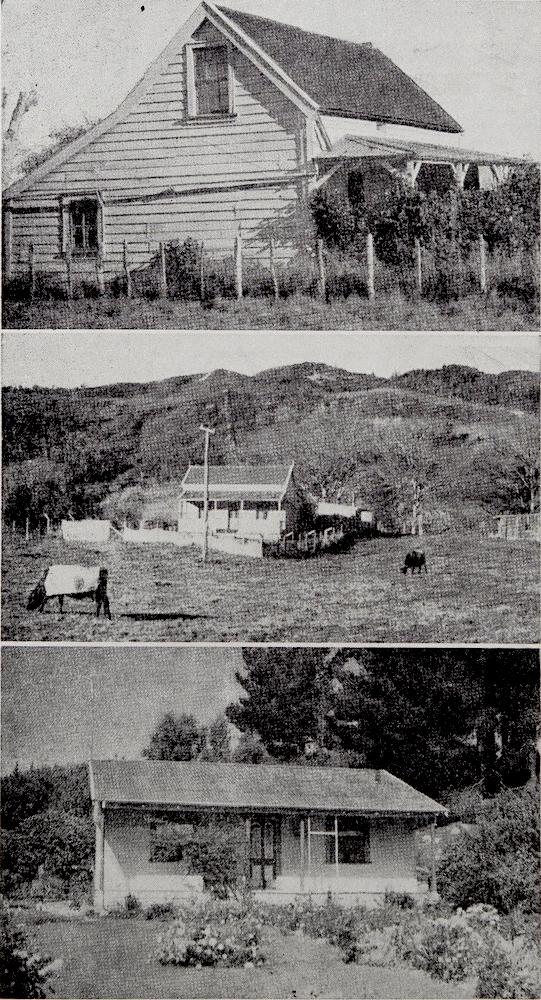

Cottages

Although the large homesteads, with their size and dignity, dominated the early scene, they were not by any means the majority of the homes. Most people advanced from a two-roomed shelter to a cottage, which might be no more than two rooms and a lean-to, or, on the other hand, might be a substantial 6- or 8roomed dwelling. Hursthouse, whose comprehensive survey of New Zealand life was published in 1861, describes such homes as follows:—

Most of the country or farm houses are wooden buildings of the one-storeyed verandah cottage type. In this land of brick and stone we are apt to picture a wooden cottage as being a poor, flimsy band-box sort of thing. But in such a climate as New Zealand's these cottages may be made very comfortable dwellings, while neatly-painted, backed by trees, or embowered in gardens, their verandahs covered with jassamine, rose, peach, or vine, they often present an air of rustic elegance and sparkling beauty to which many of the stuccoed villas, and "bell and brass knocker" deformities of English villages can make no possible pretensions.

The three cottages on the right are typical of many thousands built from the early days to the present. They have two or four rooms in the main part of the house, a verandah across the front, and a lean-to kitchen at the back. Sometimes the roof is high enough for an attic bedroom to be built. This is the kind of cottage described by Hursthouse.

The details he gives of building costs are very interesting, and "A substantial verandah cottage, 32ft. square, containing say two front rooms 14ft. x 18ft. and two back rooms 14ft. x 14ft, with a kitchen detached (amply large enough for a family of half a dozen) might now cost from £150-£200 if made of wood. Cob would be about one-third cheaper."

Hursthouse's plan is typical, but there were several variations of this type. Depending on their construction, the original two rooms might form either the lean-to or part of the main portion of the larger house. Sometimes the new house was never properly built, but two more lean-to rooms were put in front of or behind the original lean-to. Sometimes, if the family was prospering or the original home was hopeless, a whole new place wag built. In some districts, particularly around Nelson, two-storeyed cottages were characteristic, the attic space under the pointed roof being utilised for bedroorns by building out dormer or gable windows, but they still remained cottages.

Homes like these have been built in considerable numbers, right up to the present day. Room for modern conveniences, such as bathroom or wasnhouse is usually made by extending the lean-to area a little further, and one end of the verandah may be closed in to form a sunporch, but the essentials remain the same Large groups of such houses, built 60 or more years ago are now deteriorating rapidly, due to the effects of the weather and borer infestation, and are among those homes most urgently in need of replacement. [360/361]

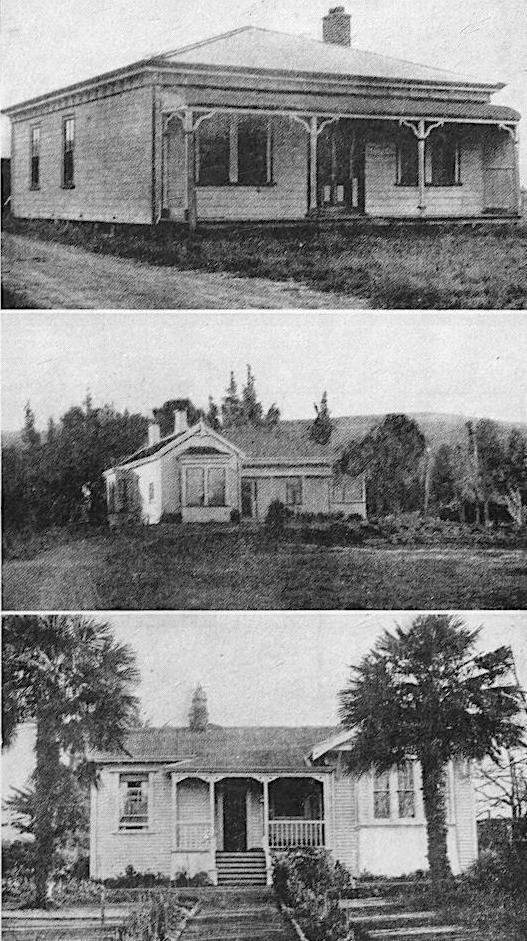

Town Houses

In later building some modifications of style are found. Particularly around 1900, when farms were well established in many 5 and transport easier, the desire for better houses and town comforts led only too often to the erection of "town houses" quite unsuitable for country conditions.

Many houses built around 1900, like those on the left, were square and box-like, with a straight central passage. The style with the bay windows and shortened front verandah was also common, and many of the unsuitable "town houses" were of this type.

Standards of design in particular deteriorated during the late Victorian period, and many New Zealand houses of this era approached the "bell and brass knocker deformities" which Hursthouse deplored.

Some of the least-desirable features of such houses were the small windows; the small narrow front verandah; the disregard for sun in planning so that main rooms often had all windows facing south; lack of sufficient space and shelter in the kitchen back-door section of the house; and far too much unnecessary decoration on the outside of the house....

Bibliography

"Brave Days." Collection of Pioneering Reminiscences. W.D.F.U. [Women's Division of the Farmers' Union], p. 87. [Reference given by Metson on p. 357]

Hursthouse, Charles. New Zealand: The"Britain of the South"... . London: Edward Stanford, 1861. See pp. 201-04. Internet Archive, from the collections of Oxford University. Web. 16 September 2025.

Metson, Norma. "Farming in New Zealand." The New Zealand Journal of Agriculture Vol. 71 (15 October 1945): 357-68. Internet Archive. Web. 16 September 2025.

Created 16 Seotember 2025