Apart from the scan of the book cover, the images here all come from our own website. Please click on them to see where they were originally used, and whether they can be reproduced (most require further permission from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, or the National Portrait Gallery, London).

The fate of the Franklin Expedition (1845) has long been the subject of historical inquiry and speculation. What happened in the Arctic wastes is still unknown, and various hypotheses have been advanced: were the crews of Erebus and Terror poisoned by defective seals on their cans of food? Were their provisions infected? Did they run out of food? Was there a mutiny? Did disease break out? No-one knows for sure how this most carefully prepared of imperial adventures, sent out in search of the North-West Passage, led only to the loss of every sailor following a desperate attempt to find safety as the dead were cannibalized. It is a tragic narrative of over-ambition and naiveté, terrible suffering and courage, pride and degradation.

The recent re-discovery of the two ships in Canadian waters has at least made it possible to establish the Expedition’s final destination and may in time provide some answers as marine archaeologists evaluate the vessels’ artefacts. All of this work adds materially to the process of understanding, recovering secrets from the cold water as surely as they are recovered from the past.

Left: HMS Erebus illuminator (fitted light) in situ, © Parks Canada, Marc-André Bernier. Right: Smaller relics of the expedition, including a hopelessly worn and cracked sea boot, © National Maritime Museum, London.

Of parallel significance is May We be Spared to Meet on Earth – Letters of the Lost Franklin Arctic Expedition. Assembled from surviving correspondence from the crew-members that was sent until they entered the waterways north of Greenland along with some desperate letters to ‘the lost’ sent after them, this expertly edited book, with Russell A. Potter as the lead editor, offers a vivid profile of the doomed endeavour. I am surprised that any letters have been preserved, and it is astonishing to find that the texts, surely the product of years of diligent transcription, run to more than 300 pages.

Making sense of the correspondence is a matter of repositioning an historical event in a reconstructed present as we learn of the events surrounding the preparation, the conduct of the ships as they sailed to Orkney and beyond to Greenland, and, most of all, the thoughts of the brave men who sailed them. The language is surprisingly detailed and direct in the Victorian idiom, and it requires no imagination to envisage events as they unfolded. The editorial touch is light, with no intrusive notes or references in the letter texts, allowing the correspondence to speak for itself.

Sir John Franklin Capt. R.N., © National Maritime Museum, London.

In the opening sections, ‘Anticipation’ and ‘Preparation’, the letters between the officers reveal the apparently labyrinthine procedures of the Admiralty as selectors finally settled on Franklin as the commander. These political machinations echo throughout, but especially interesting are the mentions of the complex physical organization that was required to provision the ships and equip the officers and men. This was, by all accounts, an arduous process: for example, Lieutenant Henry Le Vesconte writes in April 1845 of the hard work involved in adapting the vessels for Arctic conditions:

The ships are at present in dock [in Woolwich] where we are rigging each [and] stowing them while the shipwrights are altering their sterns by bracing them on abaft the stern posts an [sic] large mass of timber of the same thickness in which to work the screw propellers the engine will be put in next week we take a large supply of welsh coal and patent fuel – being bricks of coal dust and bitumen. [75–76]

These material details are reminders of the age in which the expeditions took place and the desire to direct the latest technologies to the conquest of the physical world; far from romantic, the quest was driven forward by hard-headed industrial strategies, encapsulating a stark modernity. We also hear of many other prosaic details: what the cabins were like, how the watch was organized, the officers’ uniforms, the ships’ daily routines and rituals. All of this is first-hand accounting, reanimating the mariners’ everyday lives as they engaged with their adventure.

Equally interesting are the letters’ revelations of the main participants’ characters and relationships with their shipmates and the families they leave behind. This is raw biographical material, startling in its immediacy and honesty. The names of Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames and Goodsir are all familiar to polar historians, but the letters give us an opportunity to enter their minds; for the first time they emerge from the pages as real individuals, laying bare their personalities as they explain themselves in their own words. Franklin comes over as excessively pious, writing repeatedly to his wife of ‘Gods [sic] merciful guidance & protection’ (163), while the enthusiastic Fitzjames is awestruck with a sort of naïve wonder at the sights of the voyage north and its marine animals, noting how walruses, ‘bewhiskered and betusked’, are ‘delightful’ (202). Subtler nuances are added by Goodsir’s reflections and diligence as he contemplates his role on board as a naturalist, and by Le Vesconte’s quiet worrying about the future. They seem unlikely shipmates, although it is constantly noted that they get on with each other, with correspondents speaking kindly of their comrades, held together by a shared purpose and determination, a ‘harmony’ cemented by ‘good will’ (230). Franklin particularly is the subject of admiration and love as ‘Quite a hero’ who knows how to build relationships; as the Ice Master James Reid remarks, with touching naiveté, he is ‘very fond of me’ (67). Franklin, it seems, had good relationships with his officers, and also with his working-class crew.

Lady Franklin as a young woman: a chalk portrait of 1816 by Amélie Romilly, © National Gallery London (Primary Collection, NPG 904).

However, the most intense feeling is reserved for the families. Goodsir writes to his anxious father and Franklin and several of the crew to their wives and children, always with loving tenderness as they reassure them that all will be well. Knowing the outcome, this is hard reading, a portrait of brave men whose emotional lives were rooted in their domestic relationships. Far from being arrogant imperialists or adventurers, the letters make clear they were simply doing a job, one undertaken out of duty, and the need for advancement, rather than indulgence.

Of course, their attitudes are nuanced by class. For Goodsir, his involvement in the Expedition seems to be motivated by his desire to excel – and to make his father proud of him despite his father’s ‘much anxiety’ at the venture’s ‘extreme danger’ (30). The dynamic of a worried parent and his (adult) child oscillates troublingly throughout these exchanges. For many at the lower end of social scale, on the other hand, their involvement in the Expedition was a matter of economics; they needed the money in order to support their families. Notable is the missive from James Reid, who writes to his ‘Loving wife’ (64) about the advances on the wages he will receive, and makes a point of telling her she will be financially supported in his absence and in the event of his death (67).

All such details encapsulate the essentials of the voyage and the culture that sent it on its quest. The letters allow us to see the Admiralty’s ambitions, the physical context in which the Expedition was mounted, and the dreams and doubts of those who set sail. And it is notable that many were troubled thinking about the outcome. The experienced Crozier writes of his uncertainties, hoping to ‘do something worthy of the country’, but nagged with many ‘anxieties’ (239); Franklin takes the fatalistic view that they are all in God’s hands; and Reid deflects his fear by claiming it ‘never comes in my head’ (67). Danger is there from the start, even if optimism and caution are carefully balanced, at least in the participants’ words to their loved ones.

Left: HMS Erebus in the Ice, by François-Etienne Musin, 1846, © National Maritime Museum, London. Right: A marker bearing Captain Franklin's name outside the exhibition about the Franklin Expedition at the National Maritime Museum Greenwich in 2017.

The letters also give suggestions as to why the Expedition failed, revealing details which seem, with the advantage of hindsight, to be grim portents. It is noticeable how Franklin speaks on several occasions of having a cold and influenza, hardly the best preparation for a journey to the Arctic; perhaps he caught a fatal chill when the ships entered the frozen territory? The crew members’ affection for him, as a paternalistic figure, is likewise troubling, suggestive of respect based on seniority rather than ability; perhaps he was too old for the task in hand at a time when 60 was a considerable age, and perhaps he lacked the vitality and focus of a younger man? Often it seems as if he is viewed as an amiable old buffer, a sort of Dickensian ‘liberal old man’ and ‘exceedingly good old chap’ (240) rather than the commander upon whom all of the other lives depended in one of most hostile places on Earth. The number of times when he is reported as being ‘old’ must surely ring an alarm bell, as does the emphasis on his intimate manner. Where leadership was needed he seemed to have offered friendship, and he may have failed to make the right, hard-nosed decisions as the ice-pack closed in.

The question of competence is more generally posed, given the assumed expertise and long-standing experience of those on board. Fitzjames writes on how easily they seemed to have lost their way even before they entered the unknown geography, noting how they wasted ‘the whole of the 3rd [July 1845] by some extraordinary mistake’ and ‘mistook the locale of the Whale Islands having two charts one of which was wrong & the other not too right’. Fitzjames cheerily dismisses the error as an ‘unavoidable’ accident (227) rather than ineptitude, but given that the Expedition would eventually be lost in the ice, and the sailors unable to find their way to safety in northern Canada, such sloppiness is ominous. If they can’t use the charts of known lands and seas correctly, how would they fare in the featureless unknown?

Another telling sign, and perhaps the ultimate cause of the mariners’ death, is contempt for the Inuit, whom they meet for the first time in Greenland. It has been argued in several histories that the sailors did not survive because they would not cooperate with the native people they met when they had abandoned ship, and there is plenty of evidence that they regarded the Inuit as racially inferior – as dirty (223) and child-like, in need of the civilizing influence of their Danish masters (237). Such an attitude is unlikely to have led to the crew’s trusting or seeking help from those whom it is known they encountered at the moment of greatest crisis. The north may have been new to white men, but it wasn’t to the Inuit, who knew how to survive.

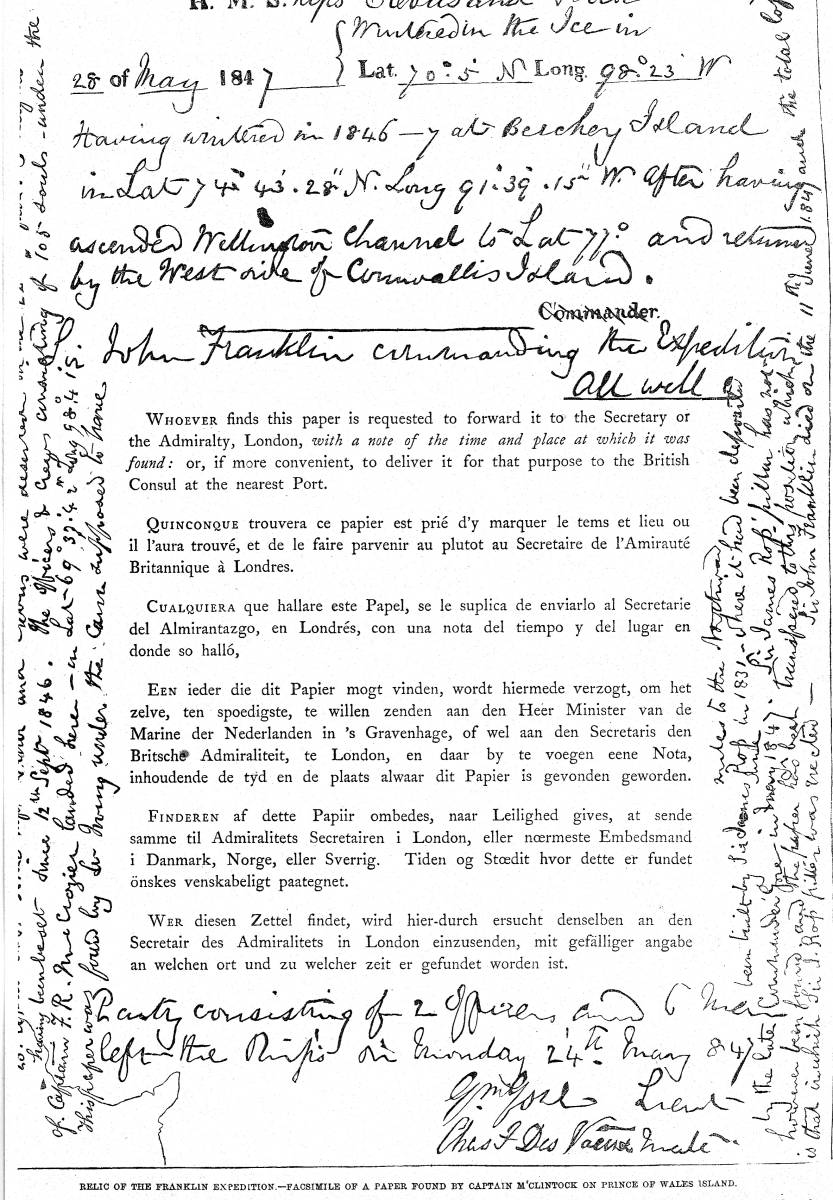

Relic of the Franklin Expedition. — Facsimile of a Paper found by

Captain M'Clintock, RN, Commander of the Final Expedition

in Search of Sir John Franklin, on Prince of Wales Island.

Of these issues we can only speculate, but May We be Spared to Meet on Earth certainly allows us to consider the personalities, attitudes, beliefs and situations of this courageous band of Britons. Although there are no direct editorial interventions – with original, often inaccurate spelling and punctuation being preserved to indicate differences of class and education – navigation of the material is facilitated by a general introduction, by introductory essays for each of sections, and by chronologies, detailed notes, maps, illustrations, and informative appendices. These contain wide-ranging and meticulously researched information, written with clarity and directness. My only slight cavil is the omission of the famous photographs of the main players; it would have been instructive to see the faces of the characters whose inner thoughts are so touchingly revealed. Nevertheless this is an exemplary book of dedicated scholarship and learning, presenting its startling material in an accessible form. Its contribution to study of the Franklin Expedition is highly significant, and it will undoubtedly be the cornerstone of all future writing and research on this most tragic and fascinating of polar explorations.

Bibliography

[Book under review] May We Be Spared to Meet on Earth: Letters of the Lost Franklin Arctic Expedition. Edited by Russell A. Potter, Regina Koellner, Peter Carney, and Mary Williamson, with a Foreword by Michael Palin. Montreal & Kingston: McGill University Press, 2022. 481 pp. ISBN978-0-2280-1139-2. £25.77.