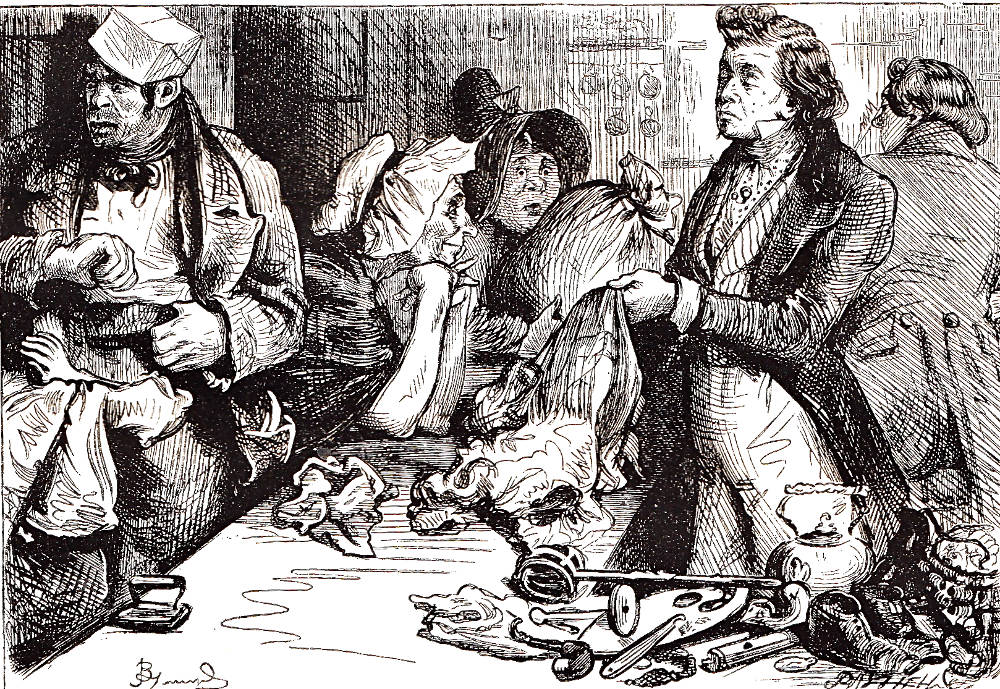

The Pawnbroker's Shop. Fred Barnard. 1876. The man at left wears a rectangular paper hat typical of many manual workers.

Dickens’s Sketches by Boz describes an early nineteenth-century institution whose very existence few members of the respectable middle-class would even acknowledge, the pawnbroker’s shop, which in the colloquial phrase was "uncle's" — the resort of the desperate whom "profligacy or misfortune drives . . . to seek the temporary relief" that such a place offers in return for their last few precious possessions, such as the little library of novels that Charles Dickens as a boy so loved, but which his father, in extreme financial straits, had to pawn. As is typical of Barnard's work, he has moved in for the closeup; although still behind the counter, the point of view he has adopted complements that of Cruikshank's The Pawnbroker's Shop (1839), revealing a variety of expressions, from the bemused expression and engaged posture curiosity of the middle-aged client to the look of concern of the next client (centre), fearing perhaps that the broker is going to give her less than she needs, to the clinical aloofness of the pawnbroker's agent as he examines the garment. Although he is immediately beside the old women, the rough-looking chap in the artisan's paper cap disregards them.

Dickens’s Description of a Pawnshop in London slums

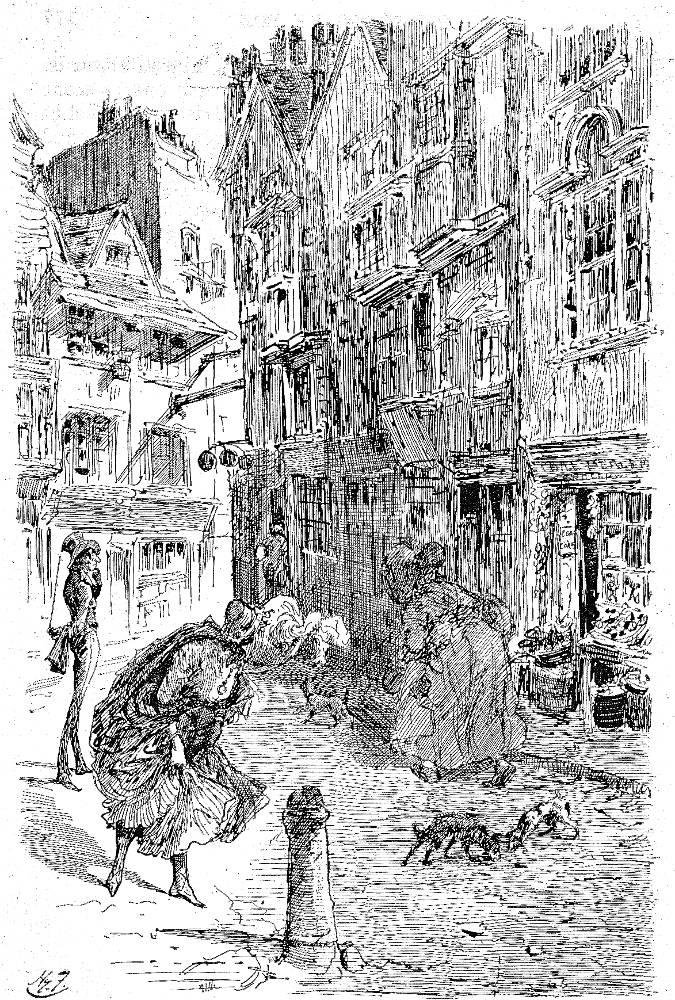

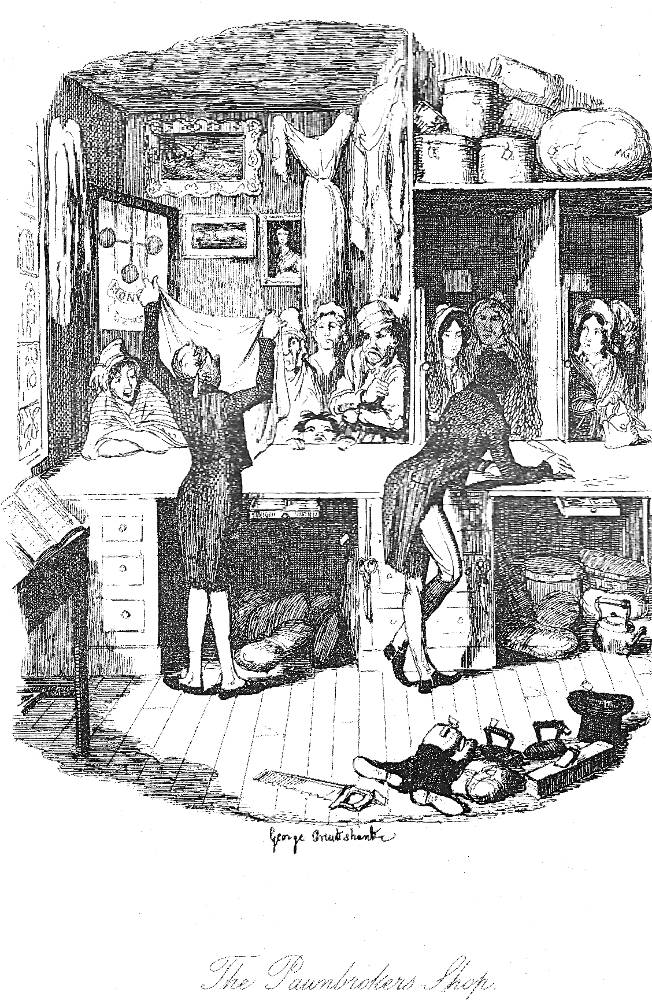

The pawnbroker’s shop is situated near Drury-Lane, at the corner of a court, which affords a side entrance for the accommodation of such customers as may be desirous of avoiding the observation of the passers-by, or the chance of recognition in the public street. It is a low, dirty-looking, dusty shop, the door of which stands always doubtfully, a little way open: half inviting, half repelling the hesitating visitor, who, if he be as yet uninitiated, examines one of the old garnet brooches in the window for a minute or two with affected eagerness, as if he contemplated making a purchase; and then looking cautiously round to ascertain that no one watches him, hastily slinks in: the door closing of itself after him, to just its former width. The shop front and the window-frames bear evident marks of having been once painted; but, what the colour was originally, or at what date it was probably laid on, are at this remote period questions which may be asked, but cannot be answered. Tradition states that the transparency in the front door, which displays at night three red balls on a blue ground, once bore also, inscribed in graceful waves, the words "Money advanced on plate, jewels, wearing apparel, and every description of property," but a few illegible hieroglyphics are all that now remain to attest the fact. The plate and jewels would seem to have disappeared, together with the announcement, for the articles of stock, which are displayed in some profusion in the window, do not include any very valuable luxuries of either kind. A few old china cups; some modern vases, adorned with paltry paintings of three Spanish cavaliers playing three Spanish guitars; or a party of boors carousing: each boor with one leg painfully elevated in the air, by way of expressing his perfect freedom and gaiety; several sets of chessmen, two or three flutes, a few fiddles, a round-eyed portrait staring in astonishment from a very dark ground; some gaudily-bound prayer-books and testaments, two rows of silver watches quite as clumsy and almost as large as Ferguson’s first; numerous old-fashioned table and tea spoons, displayed, fan-like, in half-dozens; strings of coral with great broad gilt snaps; cards of rings and brooches, fastened and labelled separately, like the insects in the British Museum; cheap silver penholders and snuff-boxes, with a masonic star, complete the jewellery department; while five or six beds in smeary clouded ticks, strings of blankets and sheets, silk and cotton handkerchiefs, and wearing apparel of every description, form the more useful, though even less ornamental, part, of the articles exposed for sale. An extensive collection of planes, chisels, saws, and other carpenters’ tools, which have been pledged, and never redeemed, form the foreground of the picture; while the large frames full of ticketed bundles, which are dimly seen through the dirty casement up-stairs—the squalid neighbourhood—the adjoining houses, straggling, shrunken, and rotten, with one or two filthy, unwholesome-looking heads thrust out of every window, and old red pans and stunted plants exposed on the tottering parapets, to the manifest hazard of the heads of the passers-by — the noisy men loitering under the archway at the corner of the court, or about the gin-shop next door — and their wives patiently standing on the curb-stone, with large baskets of cheap vegetables slung round them for sale, are its immediate auxiliaries.— "The Pawnbroker's Shop," Chapter 23, Sketches by Boz

Left: The Pawnbroker's Shop. Harry Furniss. 1910. Right: The Pawnbroker's Shop. Fred Barnard. 1876. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. "The Pawnbroker's Shop." "Scenes," Chapter 23, Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 138-144

Dickens, Charles. "The Pawnbroker's Shop." Chapter 23 in "Scenes."Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 88-92.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 23, "The Pawnbroker's Shop." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 177-85.

Last modified 11 May 2017