hroughout the eighteenth century, the English landed aristocracy, anxious to see all social and economic obstacles to its enrichment removed, had dismantled the paternalism and state interventionism put in place by the Tudor sovereigns. In the early years of the nineteenth century, Parliament eventually repealed what was left of the old laws that, at least in theory, still protected the labouring classes – this at the very moment when factory work, and with it the systematic use of women and children, began to expand. In 1814, as Harold Perkins puts it, "the destruction of the machinery of industrial paternalism was complete" (189; see also 63-66, 183-90). In the woollen districts of Yorkshire, nothing could henceforth restrain the exploitation of children (and grown-ups) in the spinning mills.

It was in this context that in October 1830 Richard Oastler irrupted onto the West Riding economic and social scene with a letter (followed at intervals by three others until March 1831) denouncing the "enslavement" of young children in the factories of the county. Entitled "Yorkshire Slavery," the letter created a sensation and a scandal. It aroused the emotions from which the factory movement was to emerge, and more precisely still the ten-hour-movement for the restriction by law of the workday in factories. Oastler soon became one of its most prominent strategists and agitators, especially in the early years, and through it embarked on his resistance to a liberal, capitalistic, industrial order which, as an ultra-Tory attached to an organic, paternalistic, rural Anglican old England, he had no love for, and looked on as a menace to the commonwealth.

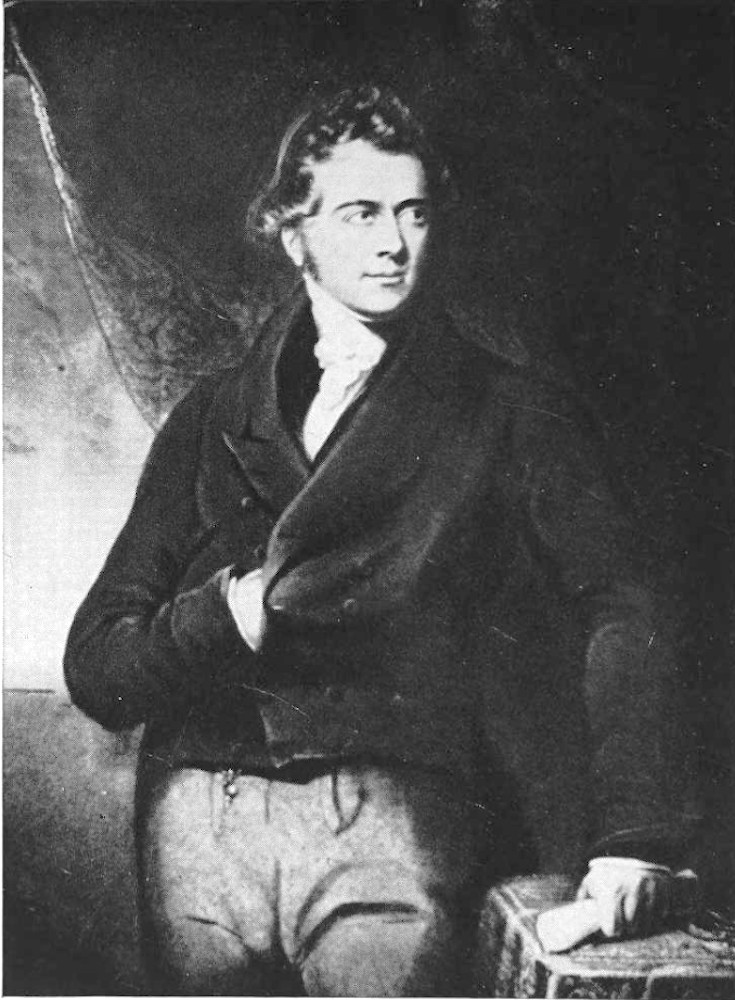

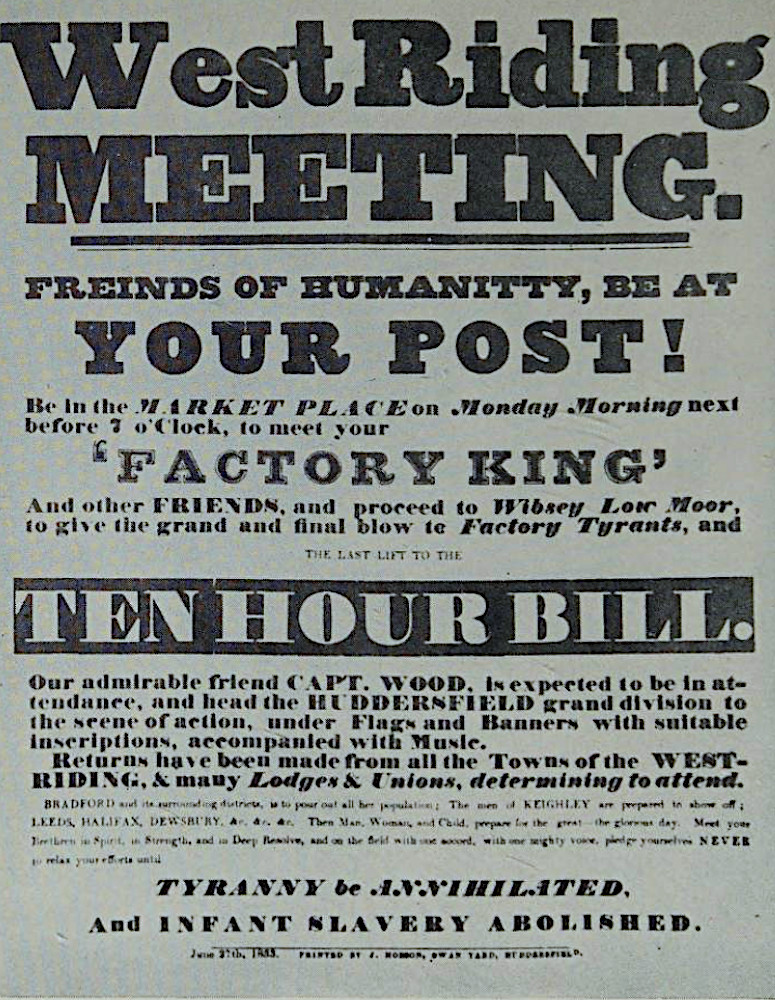

Left: Richard Oastler, at the beginning of his public career. Driver, facing p. 23. Right: One of the posters calling for the great Wibsy Low Moor demonstration on behalf of the Ten Hours Bill, 1 July 1833. Driver, facing p. 231.

Following his four letters published in Leeds periodicals1 and his April 1831 manifesto, To the Working Classes of the West Riding, which urged the Yorkshire artisans to demand that their future Members of Parliament pledge themselves to vote for a bill curtailing the day's work to ten hours, the Huddersfield popular radicals contacted him.2 Their meeting at Fixby Hall where he resided as steward of the estate that his master, Thomas Thornhill, owned in the vicinity of Huddersfield, resulted in the Fixby Hall Compact whereby the two parties committed themselves to collaborate loyally on the issue of factory work despite their political differences. The Compact was never dissolved, and from 1837 was extended to the struggle against the new Poor Law passed in 1834. It enabled Oastler to exercise his influence over all the popular movements in Yorkshire until the late 1840s. Thus, was born in the West Riding a singular assemblage of ultra-Tories and popular radicals, of paternalistic manufacturers and bankers, reactionary clergymen, and squires on one side, and of radical small traders (sometimes revolutionary and republican) and workers on the other. Staunchly supported by The Times from 1834, this alliance was cemented by Oastler's magnetic populism and moral sway.

Left: Oastler's employer, Thomas W. Thornhill, Aquir of Fixby. Driver, facing p. 470. Right: Fixby Hall near Huddersfield, c. 1830. Driver, facing p.22.

Until 1838 the latter and his associates mobilized working men and women in their tens, sometimes hundreds of thousands to demonstrate in favour of the ten-hour day or the repeal of the new Poor Law in gigantic rallies and marches, making abundant use of long, fiery speeches, banners, bands, torchlight processions, burnt effigies of mill owners. In addition, there were long, vociferous, at times violent campaigns to get ultra-Tories or radicals elected to the Commons, and the riotous reception of the people dispatched by London in 1833 and 1837 either to investigate the conditions of labour in the manufactories or to locally enforce the new Poor Law. It was at that time, during the campaign against the new Poor Law, when his discourse often brought him to the verge of sedition, that Oastler's career as an agitator reached its peak and his hold on crowds was the strongest. In March 1838 the Northern Star of Feargus O'Connor with whom Oastler had been sharing the same platforms for a year portrayed him as "the Father of the poor, the Defender of the oppressed and the Dread of the tyrant" (Driver 378).

What Oastler was then orchestrating was one of those social movements (as defined by Charles Tilly) that only became possible from the late eighteenth century with the rise of modernity and the accompanying emergence of unintegrated and turbulent urban masses.3 These new forms of popular contention, the only ones worthy of the name of "social movement" according to Tilly, were long campaigns of protest fuelled by precise demands during which agitation never abated in between flashpoints. The historical peculiarity of the Oastlerian protest, however, is that it was not intended to advance change, but to resist it. At a time when many popular radicals still drew their inspiration from memories of a disappearing rural world and aimed by their actions to obstruct the expansion of machinery and industrialism, Oastler found it comparatively easy to fire a popular opposition that was both radical (its goal being to overthrow the newly-dominant value system) and reactionary (in that it wished to restore ancient norms).

But direct action alone could not suffice. A social movement can only catch on and last if it succeeds in mobilizing a large number of individuals. That is only possible if its leaders manage to produce, through speeches and writings, what some sociologists call an "injustice frame" (e.g. see Gamson, chs 3,6 and 10) that encompasses the whole of national reality as they wish to represent it, exclusively made of hardships and sufferings. The perimeter of this frame also contains the images, symbols, situations, arguments which lend support to that version of reality, constitute a counter-hegemonic narrative, and are likely to give rise to an "insurgent consciousness," in other words a collective feeling of injustice and revolt which supplies the movement with its dynamic.

As regards the 1830s and 1840s, this injustice frame was drawn by the anti-industrial, anti-liberal rhetoric which pervaded the radical discourse, be it Tory or popular. With Oastler the starting-point of this rhetoric was the denunciation of the manufactory and the machine as the agents of death of a literally monstrous4 system, capitalist industrialism: "The horrible factory system is making a charnel-house of England" (The Fleet Papers, 10 April 1841, 115). Oastler declares that he is not opposed to the machine, but he means the hand-driven machine, the one that was the basis of the cottage system's prosperity, because it made it possible to produce more without working more and without changing anything to the domestic mode of production.5 But as soon as the machine, too big, too complex, creates the factory, it becomes an instrument of the devil,6 compelling the labourer to work harder and longer than before for less than before, making tasks heavier that it should have lightened or, on the contrary, bringing about unemployment and destitution through overproduction.7 The manufactory itself is a place of physical degeneration in which a quasi-Gothic terror prevails, where blows rain down and the overseer's whip cracks. A rhetoric of pathos runs through Oastler's discourse. The body in pain, the martyred body of the factory hand becomes the emblem of an economic system devoid of humanity8 and the horrifying manifestation of its true nature. The plantation metaphor recurs as a leitmotiv of great emotional strength among the popular masses who had fervently supported the abolitionists. The new Poor Law lent additional force to this slavery metaphor. Oastler portrays it as a mechanism for supplying the factories with a workforce of paupers transported from the South of England which thus has been turned into a huge slave market.9

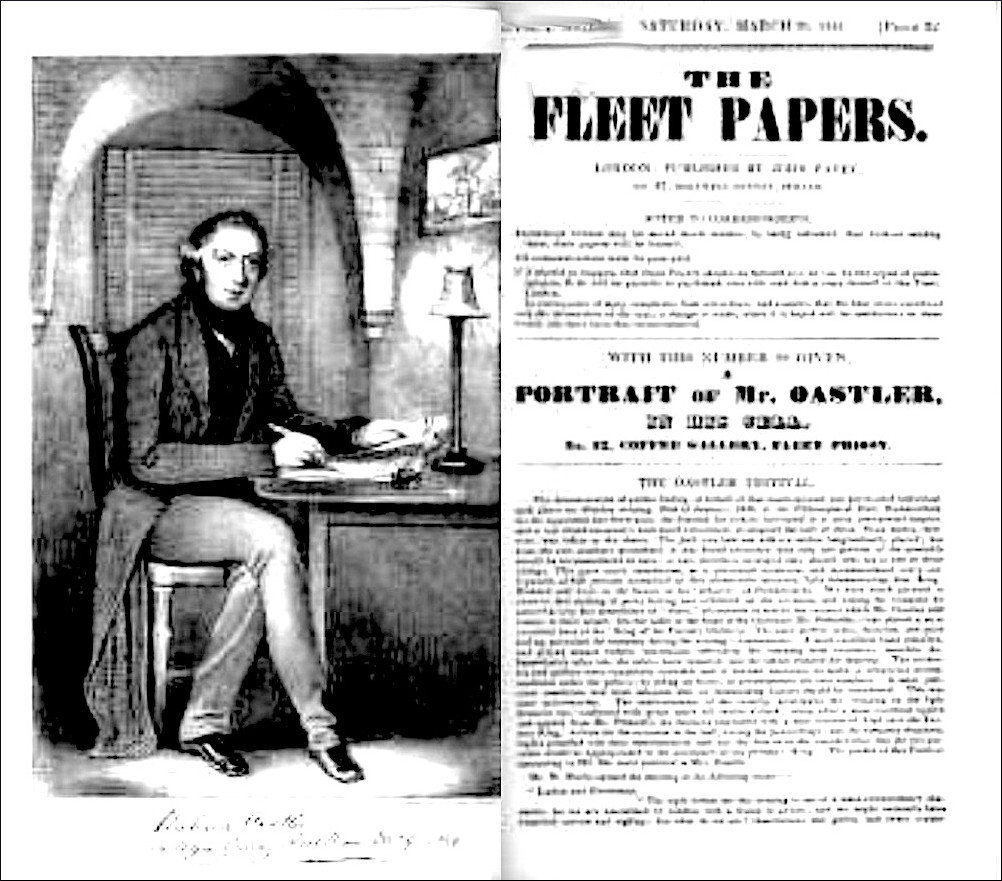

Portrait of Oastler in the Fleet, The Fleet Papers, Saturday 20 March 1841.

The reference to white slavery, sure to transfer popular indignation from plantation to factory, was made all the more effective in Oastler's discourse as it was intensified by the frequent insertion of vignettes meant to rouse repulsion and incite revolt against a system in which human beings are subjugated to the quest for profit, and which therefore had substituted the laws of political economy for the laws of God. Thus, in April 1844 in Manchester when he recalls a woman seen several years before in a spinning factory of the city, working "naked to her waist" in the suffocating heat, although she was still breast-feeding: "[I knew it] because her full breasts were boiling over, and the milk was oozing from her nipples, and, mixing with her perspiration, dropping together upon that Manchester factory floor."10 A scene of horror 11 made even more shameful as the woman was not alone; a man, who was not her husband, worked by her side, he himself half-naked. Thus, whether true or cleverly invented, the scene enables Oastler to denounce not only the economic exploitation, but also the assaults of the factory system on the sexual, ethical, domestic values which were at the heart of the people's moral code.

Until around 1830 the working-class family was both patriarchal and cooperative, particularly in the cottage industry areas. The machine atomized that traditional family, driving wives and children into the mills, making fathers and husbands often redundant. To advocate a return to a more traditional mode of family life and the restoration of the family as a unit of domestic production was therefore likely to seduce the crowds thronging at Oastler's meetings or those reading his pamphlets. Time after time, therefore, he stressed the unnatural, anti-Christian order that now characterized the English family. Its unity had been fractured, the home destroyed, the roles within it reversed; the parents' authority was defied, the girls no longer received any kind of domestic education and in the factories exchanged virtue for vice, young children no longer had any time to play and babies were fed on laudanum rather than on their mothers' milk.12 Oastler made use again of this unifying theme of the disintegrated family during his campaign against the new Poor Law, indefatigably emphasizing that the 1834 law not only meant confinement in new Bastilles and vile food, but above all the enforced separation of those God and nature had united, fathers, mothers, and children.13 At the core of Oastler's thought there was therefore an ideology of domesticity14 which allowed him to stand at the confluence of radicalism and traditionalism, and thus to awaken the greatest possible number to the inequities of the world into which they had been thrust by the machine, the manufactory, the "philosopher"15 and the "capitalist."

To stoke up that insurgent consciousness which alone can make a social movement endure, Oastler could also tap three other resources, all accessible to the crowds he addressed: patriotism, nostalgia, and the Bible. He made abundant use of the language of patriotism. One of the main strands of his discourse was that Saxon freedom abandoned by the popular radicals after 1832, but very useful to Oastler to denounce the servitude imposed on free-born Englishmen and, consequently, to depict his opponents as an anti-national faction (see Colley 336-42). At his meetings the masses still bawled out "God Save the King/Queen" and "Rule Britannia." Patriotism, as Oastler saw it, was the idea that beyond their partisan preferences and personal interest, everyone had an obligation to safeguard the rights of "every man born in England" to live well there.16 He therefore fulminated against those who wished to force the abominations of the factory system or the new Poor Law on "free-born Englishmen," on "English families" (Damnation! Eternal Damnation..., 10 and 12). He frequently used the word "Briton," making the most of its patriotic connotation: his letter on slavery in Yorkshire is simply signed "A Briton"; he declared "un-English" to burst into effusions over West Indian slavery, but to remain stonily indifferent to the practice of "white slavery" by British manufacturers, "un-English" to consider that the English would be well-advised to buy their food from abroad, "un-English" to countenance an economic policy that left the people of England no choice but emigration. His purpose was clearly formulated in an 1835 letter: "A strong army of patriots may yet arise in the plains of England, resolved to assert their rights and tear laurels from the brow of Capital" (qtd. in Driver 231).

However just as effective as the language of patriotism was a rhetoric of nostalgia of which Oastler's discourse was a perfect example at a time when nostalgia was running through the entire anti-modern, anti-industrial, anti-capitalist movement. Oastler always depicts the recent past as a Golden Age, an Eden in which work was light and free, the community made up by the family, the village, the independent artisan producers fraternal and happy, nature a source of pleasure and strength. It was not, in his case, the nostalgia of one resigned as in Goldsmith's The Deserted Village. The purpose of his evocations, of his resuscitating a lost Arcadia was to create a myth in Georges Sorel's sense of the term, an idealized representation of England (although close enough to reality to be credible) which incited the people to prepare for the struggle. In Oastler's case this myth was strictly restitutionist.17 Its sole ambition was to restore the pre-industrial past, but in the early nineteenth century its suggestive power was strong enough to work upon the minds and imaginations of men and women who had not yet forgotten where they came from and who were offered by it, instead of the smoke of towns, the mutilation of bodies, never-ending toil, the peace, beauty, and health of the fields.18 Oastler's nostalgia was no doubt reactionary, being underpinned by the idea that the forced entry of the British into industrial modernity was a Fall for them. However, that did not make it less likely to stir people to action, more so perhaps within the context of an age when remembrance of the past could still serve as a weapon.

Religion too could be an agent of resistance. In a nation in which "the prevailing conviction was that only by abiding by the requirements of Christian law could a country enjoy balance and harmony" (Bédarida 31), the Bible offered powerful arguments to convince people of the irreligion, the "infidelity" as Oastler put it, of the new Victorian order. The Home, the weekly periodical he edited between 1851 and 1855, endeavoured to lay the foundations of a social and Christian economy, and Oastler exhorted the workers (and their bosses) to read the Bible, the book not only of spiritual, but also social salvation.19 The Bible was particularly important because in it there was explicit condemnation of selfishness, and by inference of the new political economy which claimed that the pursuit of personal enrichment contributed to the growth of the general prosperity, that "covetousness is the root of all good" (The Home, 21 June 1851, 63) But covetousness was one of the most pejorative terms in Oastler's lexicon. Long before The Home it had already proved useful to expose the factory system, the new Poor Law and free trade, all three born of the selfish calculus, all three sacrificing the labourer to "their inextinguishable passion for gain" (The Fleet Papers, 19 February 1842, 59). Leaning heavily on quotations from the Bible, Oastler sought to demonstrate that it was sinful to exploit one's neighbour, that work was a right as much as property, that the working man must be the one that should profit first by the fruits of his labour,20 that the repeal of the Corn Laws and the adoption of free trade went against the Scriptures by impoverishing the many for the benefit of the few, and thus scorned "the plan of mutual dependence" willed by God.21 It was also in the name of the Bible that he called for disobedience to the law and for resistance to the implementation of the, to his mind impious, new Poor Law in the North of England (The Right of the Poor to Liberty and Life, 22).

Intellectually the biblical argument could easily be fortified by reference to the social contract, the origins of property and the Constitution. Thus, popular resistance to the new Poor Law was made legitimate by philosophy and Law. The references to the social compact and the Constitution were meant to show that the new economic system fostered public disorder, civil war even. To prove his point Oastler pressed theoreticians of natural law into service, Locke, Grotius, Pufendorf or Paley, maintaining that originally, in the state of nature, land belonged to no one in particular.22 When men decided to constitute a commonwealth in order to enjoy a more secure existence, the weak renounced their right to the land on condition that the strong and the rich protected them and ensured them decent means of subsistence. Consequently, in Oastler's view, the right of property was conditional, resting "upon one express condition, namely that every member of society should have his liberty and his life" (The Right of the Poor to Liberty and Life, 4). If this right to life and liberty was not respected — and it was not when the new Poor Law forced a man "to give up his liberty to save his life" (The Right of the Poor to Liberty and Life, 6) — one could expect, he asserted, leaning on Grotius and Pufendorf, the social compact to be broken and society to return to "anarchy, confusion, and strife," to a state of "wilderness" in which anything was fair to survive, including robbery and murder (The Right of the Poor to Liberty and Life, 11-12).

Left: Richard Oastler at the age of 48. Frontispeice to Driver. Right: Richard Oastler (1869), by the sculptor John Birnie Philip.

The constitutional argument, resting primarily on the authority of Bacon and Blackstone, but also of Hale, Coke, Holt, Eldon, added nothing more except that in this context it was not a crime to steal what one could not pay for. The British Constitution, via the Magna Carta, guaranteed individual freedom; it also guaranteed "life," the right to subsistence, by the 1601 Poor Law, the "43rd Elizabeth" that Oastler tirelessly invoked and which was, according to him, the perfect model of a law both social and Christian. It followed that paupers had a right to demand that the powers-that-be aid them, which the latter could not refuse, nor make it conditional upon their being confined in a workhouse. If the contract uniting the poor (a category that, in Oastler's terminology, was generally indistinguishable from that of the labourers) with the temporal powers was broken, neither the Crown nor the aristocracy must expect allegiance or deference from them, and they could – quotations from Bacon or Blackstone here being used as supporting evidence – lay hands on all they needed to survive. Nothing would be safe any longer, and property would be shaken to its very foundations Oastler asserts on several occasions,23 warning against a popular revolt and urging the landed aristocracy to think twice before supporting the implementation of the new Poor Law. He tried the argument out on Wellington whom he met a few times and wrote to between 1832 and 1834, but the Duke remained perfectly impervious to it.24

Oastler's purpose was not merely to dissuade the aristocracy from passing the Poor Law. He wished Wellington to understand that the people were, at the very least, the objective ally of the landowners for the aim of the "capitalists" was not only to exploit them, but also to bring down the aristocracy. The people were angry but loyal. All they wanted was to follow their traditional leaders. It thus behoved Wellington to save England by re-establishing a "paternal" government. Despite his lack of success in 1834 Oastler tried again during the Anti-Corn-Law League campaign. The aristocracy must realize, he insisted again, that because free trade led to the repeal of both the Corn Laws and poor relief, the people were "their best friends." If they did not strike an alliance with them, capitalism would triumph and the "millionaire" would replace the aristocrat and take his land for himself.25

At such times Oastler is clearly hoping to bring to fruition the political dream that all along underpinned his militancy and his resistance: the building of a new "Old England," green and pleasant, his very Jerusalem, a nation of sturdy artisans and peasants led by their old benevolent, paternal elites, bound together by what Pufendorf called a "general friendship." He never gave up his hope in the aristocracy of England (his last call, five letters To the Aristocracy of England, was made as late as 1850, see Driver 508-09) -- and he could hardly do otherwise having always been impervious to the merits of democracy and universal manhood suffrage – but his dream began to fade as early as the beginning of the 1840s when Peel, a Conservative but not a Tory, triumphed. On 20 January 1841 he wrote: "My old-fashioned party is, they say, extinct. Philosophy and Expediency have driven it from the palace, the castles, the mansions, and the houses; it now hides itself, with Christian principles, in the cottages. There, Sir, it is, I believe, taking deep root" (The Fleet Papers, 30 January 1841, 40).

But he was mistaken. The workers trusted him, admired him, followed him, worshipped him (he was their "king") not because he was a Tory, but because, although he was a Tory, he sincerely fought, without second thoughts, for the well-being of the people. But this people had its own definition of its well-being and its interests which eventually no longer really coincided with Oastler's. What the latter wrote at the end of the 1840s (Free Trade "Not Proven" in Seven Letters to the People of England) did not deter it from being increasingly tempted to go over to free trade. The Home, that Oastler launched in 1851 was still intended to be a periodical fighting for protectionism against free trade.26 In it Oastler sermonized the workers,27 tried to convince them that the liberal candidates that they now cheered in electoral campaigns, and even the leaders of the trades union movement lied to them, that "universal competition is the parent of universal poverty" ("To the Working Men," The Home, 31 July 1852, 36). He again enlisted Blackstone to demonstrate that free trade went against natural law and divine law (The Home, 26 December 1852, 181). To no avail. Significantly, even his advocacy of poor relief had become incomprehensible to the new generation of working men. The Home's circulation kept declining. In 1855 it closed.

In fact, in the new context of the 1850s, after the popular success of the 1851 Great Exhibition, at a time when working-class families began to be able to afford a very big loaf of bread, and New Model Unions were being formed which sought accommodation with capitalism, it was bound to seem anachronistic in the eyes of most workers, symptomatic of a tiresome repetitiveness and of a political system running out of ideas, to still denounce the plight of the peasantry, the horrors of the factory and the city, the tyranny of the machine, free trade, Manchesterian cosmopolitanism and even what happened to the handloom weavers several years earlier – anachronistic also to consider that only life in the countryside, industry, social and economic protectionism, a strong guardian State and naïve simple faith could create a harmonious society.

Did Oastler look for the impossible? Was his struggle a backward-looking, rearguard action? It is probable, but not entirely certain. Until the late 1840s nothing was yet firmly in place. The old world was not dead and the working men, even if they rejected the present, were not necessarily casting about for a new society. Going backwards a few decades was not unthinkable. But this would have meant preventing the liberal worldview from taking hold of the British imagination, which could only be achieved with the collaboration of a dominant social class, the landed aristocracy, or a fraction of it, which would ultimately have put tradition before profits. Perhaps Oastler failed for want of a man on horseback, the charismatic leader he sought in vain in the person of Wellington. But admittedly, already in 1830 and a fortiori twenty years later, this was really expecting a lot of an aristocracy who for the most part had long since forgotten that noblesse oblige.28

Created 1 June 2023