This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the review was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by the author, who has also added captions, and links to other material on our website. Please click on the pictures to enlarge them, and (apart from the first one, of the book cover) for more details about them.

With its cover design of holly, mistletoe, evergreens and Christmas roses, the new paperback edition of Neil Armstrong's Christmas in Nineteenth-Century England looks like an ideal Christmas gift. But it is no mere stocking-filler. Armstrong's approach to his subject is thoroughly scholarly. Researching both contemporary and critical accounts of the festive season during these decades, he subtly tweaks some of our common ideas about it and covers a wide area of popular culture in the process. As well as family life, Armstrong deals with the highly influential print industry, the growth of consumerism and the entertainment sector, developments in philanthropy and the workplace, and more.

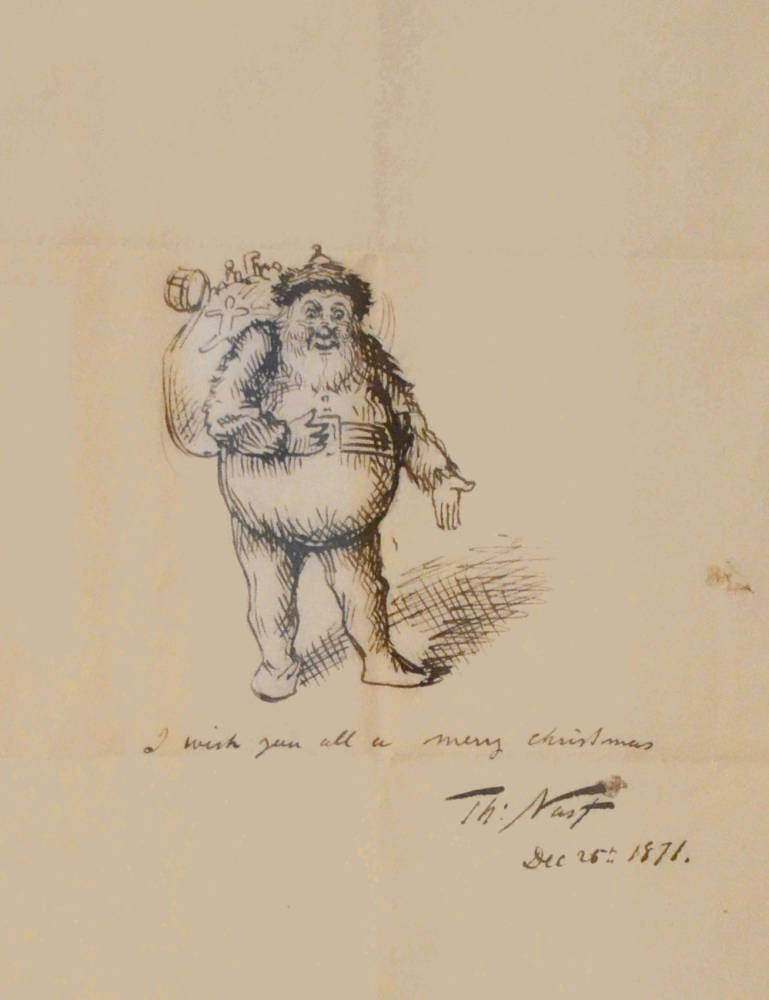

Armstrong's first chapter deals with the evolving iconography of Christmas in print — and with good reason. This was the main way in which notions about Christmas were disseminated. Take Father Christmas, for example. His origins might seem to lie in some idealised Merrie Old England. But he arrived only in the seventeenth century, and appeared in the Illustrated London News of 21 December 1844 as a larger-than-life personification of feasting and revelry. At this point in the Victorian era, he looked like nothing more than an inebriated glutton. Only gradually, by association with the Santa Claus of complex continental and American origins, and perhaps particularly with the images of him by cartoonist Thomas Nast, did his image soften. Until his iconography became fixed by the illustrated press, Armstrong tells us, he was sometimes said to sport yellow or blue attire, instead of red. Even the long beard only really became significant when Victorians started shaving theirs off. Then at last he was established and standardised as an old-fashioned, benign, and altogether grandfatherly figure.

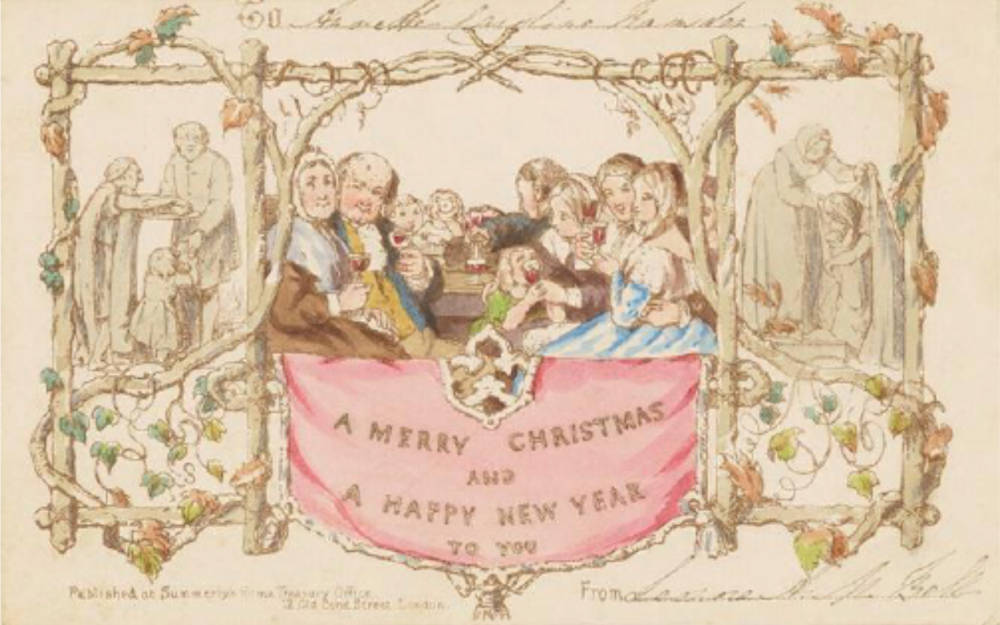

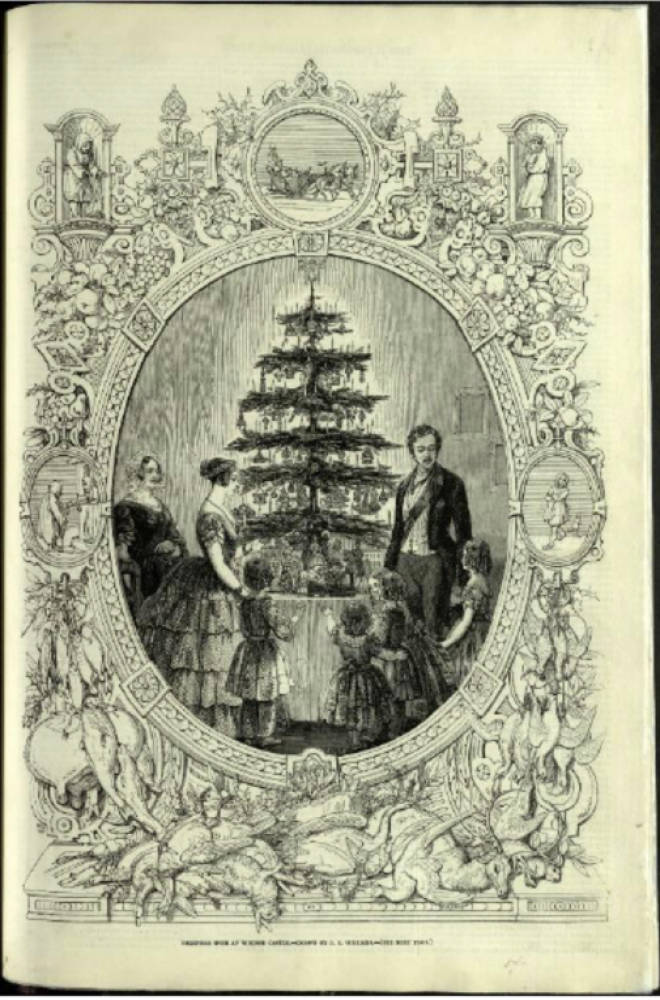

Left to right: (a) The First Christmas Card designed by John Horsley for the predecessor museum of the V&A (sold in 1846). (b) The Christmas tree at Windsor Castle, from the Christmas supplement to the The Illustrated London News (December 1848). (c) Thomas Nast's sketch: "I wish you all a Merry Christmas" (1871). [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

Other, more subtle, correctives of our view of Victorian Christmas follow. Dickens, for instance, was less central to its development than we might have thought. Far from issuing in the new Christmas package whole and entire, says Armstrong, "[w]hen the Carol first appeared in print in 1843, significant changes in the structure and meaning of Christmas were taking place which Dickens's novella failed to represent" (51). One example (although Armstrong only mentions this later) might be Scrooge's sending a boy to the poulterer's to buy a turkey on Christmas morning. By 1842, not only were shops closed on Christmas Day, but workers were agitating for a compensatory Monday closure if it happened to fall on a Sunday. The royal family too may be less central to the Victorian celebration of the holiday than we assume. When Prince Albert imported the tradition of an indoor Christmas tree from his native Germany, and the Illustrated London News of 1848 published an illustration of the family gathered round it at Windsor, the custom was sure to grow. But we have overlooked the way in which this influence was bolstered by the children's books translated from the German at this time, presenting similar family scenes. Christmas cards come in for similar treatment. Yes, Sir Henry Cole commissioned the first Christmas card and it was designed by J. C. Horsley in 1843. But, again, there were other factors in its adoption as a custom, notably the arrival on the scene of chromolithographic printing, and a vastly improved postal service.

Surprisingly, in an age when so many attended church, and new churches were being built at pace, few of the early cards were religious. Armstrong provides an interesting explanation for this: the spiritual meaning of Christmas was, he says, more slanted towards atonement in the early part of the century, only shifting to the incarnation as the century progressed. The waning of moralistic Evangelicalism affected much more than the Christmas card industry. Unreserved joy in the nativity helped to put children at the centre of the festivities, and along with that came an emphasis on gift-giving and celebrations. Christmas shopping and advertising, and seasonal entertainment, all thrived. Among the many signs of this were the popularity of children's Christmas annuals, and special events like the "Christmas Fairyland" at a Liverpool store in the 1870s, and Santa's Grotto in a Stratford (London) store, probably the first of its kind, which was visited by 17,000 children in 1888. Pantomime flourished, and half-price seats for children were introduced. These small details, these facts and figures, are fascinating, and indicate the changing dynamics of family life as well as the commercialisation of the season. Less happily, poorer children were recruited as performers. Like the semi-naked little girls on some Christmas cards, the exploited "pantomime waifs" remind us that not even Christmas sparkle could obscure some of the ills in Victorian society.

Remembering Joys that Have Passed Away by Augustus Edwin Mulready (1843-1904), 1873. Courtesy of Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London Corporation.

Many were aware of this at time, and Armstrong has a good chapter on the way philanthropy boomed as efforts were made to provide the poor with some of the pleasures enjoyed by their wealthy peers. Decorations, extra rations and entertainments brought Christmas cheer to the workhouses, as did the already well-established modest allowance of alcohol — a controversial extra in the days of temperance, but one which most people supported, preferring to offer the inmates a pint of beer instead of "a ton of disappointment" (115; quoted from an issue of the Liverpool Mercury in 1897). Again, children were a special focus. Charities ran Christmas campaigns for the hungry little "robins," as they came to be called, encouraging the middle class to join the richer benefactors in providing them with toys and entertainment as well as food. Entertainment in the workhouse might take the form of a magic lantern show or a band, with the opportunity for dancing.

Still, there were many who noted the discrepancy between the ideal Christmas and the one they were experiencing now. Another way in which Armstrong's book differs from a stocking-filler is in its references to the "Christmas Lament" — the recurrent complaint that the spirit of Christmas has somehow been eroded. Surprisingly, the tradition for this goes back as far as Father Christmas himself, or further. In the seventeenth century, Armstrong explains, it was put down to the fact that landowners went galloping off to London to avoid offering hospitality on their estates. However, when the festival was banned by the Puritans, previous celebrations took on a warm glow of nostalgia, which clung to them even after festivities resumed at the Restoration. The new customs that have evolved since then, and continue to evolve, cannot quite obscure those imaginary "olden times", and even seem to intensify the feeling that they have been lost. As well as providing us with a mine of scholarly information, Armstrong helps to explain the persistent refrain that, for one reason or another, Christmas simply isn't what it used to be.

Links to related material

- Christmas Celebrations in Nineteenth-Century Britain

- Victorian Christmas cards: An Everyday Work of Art

Bibliography

[Book under review] Armstrong, Neil. Christmas in Nineteenth-Century England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020. Paperback. 193 + xvi pp. ISBN 978-1-5261-4993-0. £12.99.

Created 20 November 2021