[The following passage from the Chambers 1838 Gazetteer of Scotland appears on pages 292-97. In transcribing the Internet Archive online version, I have occasionally added paragraphing for easier on-screen reading. — George P. Landow.]

new object of excitement soon appeared in the person of Mary, Queen of Scots, who, on the 9th of August, 1561, arrived at Leith from France, to take possession of the throne of her fathers, and was received by her subjects with every demonstration of welcome and regard. On the 1st of September she made her entry into Edinburgh with great pomp, and nothing was neglected which could express the duty and affection of the citizens towards their new sovereign. On the Sunday after her arrival, however, a crowd of people assembled at the palace, and could hardly be restrained from interrupting the Roman Catholic service performed in her private chapel, and taking vengeance on the priest who officiated. Such conduct was followed up by intolerant proclamations, issued from the magistracy, and levelled at the religion of the queen, and in 1563, during the temporary absence of Mary, a multitude of persons broke into her chapel, and in a riotous manner interrupted the service.

The marriage of the queen to Darnley gave a different current to affairs, as they related to the kingdom and the metropolis. Darnley was proclaimed king at the market-cross on the 28th of July, 1565, and next morning was married within the chapel of Holyroodhouse. On Saturday the 9th of March, next year, the murder of Rizzio took place; and on the 19th of June following the queen was delivered of a son, in whose person the crowns of the two kingdoms were destined to be united. On the 10th of February, 1567, Darnley having been lodged in a solitary house, in a place named the Kirk of Field, near the site of the present university, was blown up with gunpowder; and Bothwell, who was not without cause suspected of the murder, having divorced his wife, was married to the Scottish queen, in the palace of Holyroodhouse, on the 15th of May, 1567. From the 14th to the 19th of the previous April, the parliament sat at Edinburgh, and in this week was passed the first British act of toleration, upon the principles of indulgence of conscience, and regard to freedom. As Mary was the patroness of this famous act of the Estates, she, as well as her legislators, enjoys the honour arising from so meritorious a measure.

The infamous marriage of the queen and Bothwell led to fresh disturbances in Edinburgh; and on the 6th of June they fled from Holyrood to Borthwick castle, and from thence to Dunbar. Five days after, the associated insurgents, amounting to three thousand men, marched into the city, and took possession of the seat of government. On the 14th, the queen was brought from Carberryhill to Edinburgh, where she was deposited in the house of Sir Simon Preston, the provost (the site of which is now covered by the first building in the High Street, west of the Tron Church), amidst the most wanton popular insults. Next day she was carried a prisoner to Lochleven castle. A government was then formed in the name of James VI., the infant son of Mary, and on the 22d of August the Earl of Murray was proclaimed regent at the cross of Edinburgh. The assassination of the Regent on the 21st of January, 1569-70, at Linlithgow, threw Edinburgh into great confusion. The town was placed in a condition of defence, and the senators of the college of justice threatened to leave a place so constantly engaged in civil discords.

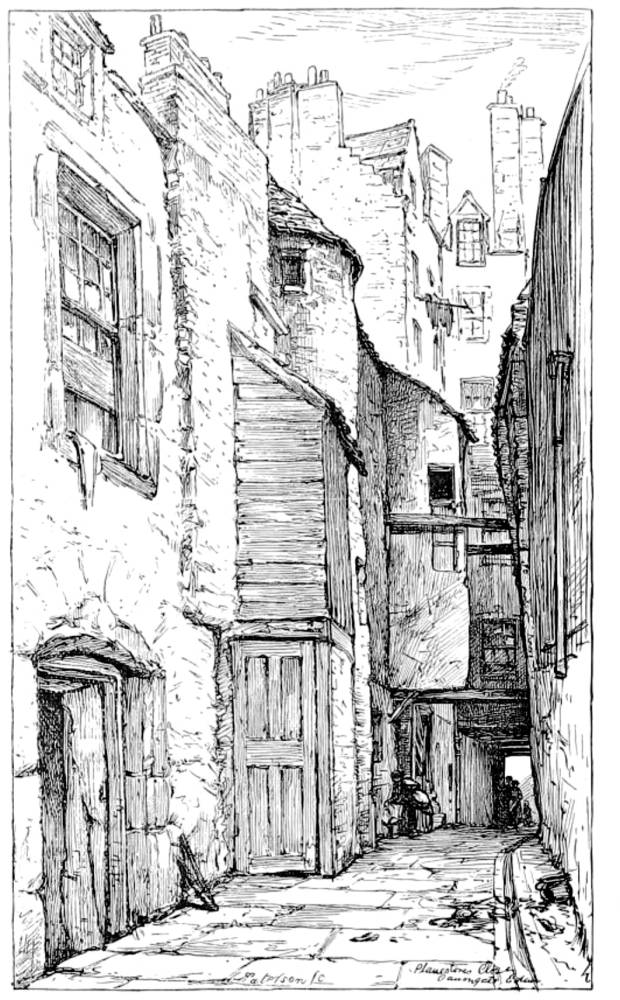

Planestones Close, Canongate by R. Kent Thomas. 1879. Click on image to enlarge it.

In the year 1571, during the regency of the Earl of Lennox, Kirkcaldy of Grange, the provost of the town and governor of the castle, declared for the captive queen, whose party held a parliament in the Tolbooth, while another parliament under the king or regent's faction held its meeting in the Canongate. Kirkcaldy issued a proclamation declaring Lennox's authority to be unlawful and usurped, and commanding all who favoured his cause to leave the town within six hours, seized the arms belonging to the citizens, planted a battery on the steeple of St. Giles', repaired the walls, and fortifying the gates of the city, held out the metropolis against the regent. Huntly, Home, Hemes, and other chiefs of the queen's faction, repaired to Edinburgh with their followers, and having received a small sum of money and ammunition from France, formed no contemptible array within the walls. On the other side, Morton fortified Leith, and the regent joined him with a considerable body of men. For nearly two years a kind of predatoiy war was carried on, with all the virulence which religious and political hatred could inspire, and Edinburgh was generally its centre. At last a treaty was concluded; but, Kirkcaldy and several others refusing to be comprehended in it, Morton, now regent, solicited the assistance of Elizabeth, who with alacrity sent a small army from Berwick to Edinburgh. The castle was then besieged in form, and after a desperate resistance, the garrison was forced to capitulate, on the 29th of May, 1573. Kirkcaldy and his brave associates surrendered on promises of good treatment; nevertheless the metropolis on the 3d of August following was stained with the execution of this brave soldier and his brother, both being hanged at the Cross upon a gallows, which, from different circumstances, we are induced to believe stood in constant preparation at this period, to destroy the numerous victims of civil discord.

At length the young king himself entered upon public life. Having summoned a parliament at Edinburgh, in October 1579, he resolved to remove thither from Stirling, and the citizens exerted themselves to offer him a splendid reception. On the 17th of October, James arrived in the metropolis, and passed to the palace of Holyrood, with a cavalcade of two thousand horse, while the castle " shot vollies" as a salute, and the people uttered their usual noisy demonstrations of joy. On the twenty-third of the same month, the king held his first parliament in person, in the usual place of meeting in the Tolbooth. In December, 1580, the Earl of Morton, late regent, was accused of being accessary to the murder of Darnley, of which imputed crime he was afterwards convicted. This most flagitious noble was put to death at Edinburgh, by an instrument called the Maiden, similar in its construction to the modern French guillotine, and, as is pretty well attested, an invention introduced into the country by himself.*

The erection of the university of Edinburgh about this period, under the patronage of James VI. assisted considerably in raising the character of the city. Ever since the destruction of the religious houses, the state of education in the metropolis had been in a ruinous condition, notwithstanding that what is called the High School had existed from an early period in this century. After the establishment of the Reformation, the citizens loudly complained of the increasing number of the poor, and the defective state of the schools, and other seminaries of learning. To enable the community to provide for their poor, Queen Mary bestowed upon them all the houses belonging to the religious foundations within the city, with the lands and revenues appertaining to them in any part of the kingdom. This grant was confirmed by James VI. who also bestowed upon them a privilege of erecting schools and colleges, for the propagation of science, and of applying the funds bestowed on them by his mother, Queen Mary, towards building houses for the accommodation of professors and students. He further gave full power to every one to give in mortmain, lands, or sums of money, towards the endowment of these schools and colleges, giving to the town-council liberty to elect, with advice of the ministers, professors in the different branches of science, "with power to place and remove them as they shall judge expedient; and to enjoin and forbid all other persons from teaching," &c. within the city unless admitted by the council. * This machine was generally used after this period in judicial executions, for crimes against the state, and for this purpose was removed from place to place over the country as exigency required. It now finds a place among the curiosities of the Antiquarian Museum in Edinburgh.

This grant and all the subsequent ones made by James VI. in favour of the university, were ratified by parliament; and all immunities and privileges bestowed upon it, that were enjoyed by any college in the kingdom. Notwithstanding these grants, the town council did not find it convenient to establish a university till their funds for doing so were increased; which did not occur till 1581, when they got a legacy of 8000 merks from Robert Reid, Bishop of Orkney, for the purpose of founding a college. The college of Edinburgh was consequently commenced in 1581, in the buildings previously occupied by the collegiate church of St. Mary in the Fields, and in 1583, its first professor was appointed. James, like his immediate descendant Charles I., was a warm friend of learning, so far as university education was concerned, and took considerable pains to nourish this infant institution. He watched over it with a paternal care, endowed it with certain church lands and tithes, and finally, in 1617, when paying Scotland a visit as a British monarch, gave orders that it should be called King James' College. The attempts made by James on his accession to the nominal sovereignty, to procure* a moderate share of power, so as to carry on the government of the country, met, as is well known, with the most violent opposition from the nobility, clergy, and other leading classes of the community, who, during the past age of anarchy, had become so headstrong as to be unable to submit to any thing like monarchical authority. On his being seized by the Ruthven conspirators, August, 1582, the pulpits resounded with applauses of the godly deed; an act of Assembly was afterwards passed, declaring the conspirators "to have done good and acceptable service to God, their sovereign, and the country;" and threatening with ecclesiastical censures those who, by word or deed, should oppose the good cause. When brought to Edinburgh, he was met by the ministers, who, with the licence then assumed by their profession, sung a psalm as they walked up the streets, expressive of the great deliverance they had lately obtained by the captivity and subjection of the king. A more amusing instance of the unrespective conduct of the preachers of Edinburgh occurred after James was liberated. Willing to show some attention to two French ambassadors, the king requested the magistrates to entertain them with a banquet; but the ministers, conceiving it sinful for Protestants to dine with Catholics, not to speak of the impropriety of holding any intercourse with France whatsoever, resolved to prevent, or at least to damp the hilarity of the dinner party, and therefore ordered a fast to be kept on the day of the feast, when three of their number preached successively in St. Giles' church, so as to occupy the day with invectives against the magistrates and nobles, who, by the king's direction, attended the ambassadors: they afterwards were with difficulty prevented from proceeding the length of excommunicating the city rulers.

On the 13th of May, 1587, a very strange conceit was executed by James. With a view to reconcile the nobles, whom civil war had long divided against each other, he made a royal banquet in Holyroodhouse, from whence he caused his contentious guests to walk hand in hand to the Cross, where the whole were entertained by the magistrates with a collation of wines and sweetmeats, and drank to each other in token of reciprocal forgiveness and future friendship. It may hese be noticed, that it was a favourite practice of James, arising from his penury, to direct the magistrates of Edinburgh to entertain his friends and ambassadors, and by this alone, independent of presents made to the king, the town funds suffered considerable injury. It is observable, from circumstantial evidence, that, partly through domestic broils, and partly owing to those severe exactions, the town was in a more ruinous and backward condition at the end of the sixteenth century than it had been in the time of James V. The town suffered severely from the plague in 1585-6, which added to its depression at this epoch.

When intelligence arrived, in August, 1588, that the Spanish Armada was approaching the shores of Scotland, preparations were made to receive it, and the magistrates of Edinburgh commanded the citizens to provide themselves with arms to prevent a descent, directing three hundred men at the same time to be raised for the town's defence. This danger passed away, but it was not alone upon occasions of national calamity that Edinburgh suffered. An occasion of national rejoicing was generally as bad. A treaty of marriage being concluded betwixt King James and Anne, princess of Denmark, the magistrates received a precept, commanding them to entertain the royal bride and her retinue, from her arrival at Leith till the palace could be fitted up for her reception. The common council, to avoid this expensive affair, presented James with the sum of five thousand merks; and some time after, the citizens, in obedience to a second precept, sent a beautiful and commodious ship to Denmark, at the expense of five hundred pounds, Scottish money, per month, to bring home the king with his royal bride. At the arrival of the happy bride, the common council, accompanied by the principal citizens, richly apparelled, joined the cavalcade which escorted her to her lodging, and afterwards to the palace; and at her marriage, which was solemnized in St. Giles' church, they presented her with a rich jewel, deposited with them by the king, as security for a considerable sum of money advanced to him, and took the royal promise for payment. "Yet," continues the historian of Edinburgh,

all the above acts of generosity, and many others, were not sufficient to secure the injured and oppressed citizens from intolerable impositions and grievous exactions; for now James compelled them to take of him the sum of forty thousand pounds, Scottish money, (part of bis wife's portion,) and to pay ten per cent, interest for the same; whereas they were then in such good credit, that some time before they borrowed money at five per cent, interest.

Besides this draining of the financial resources of the town, James was exceedingly arbitrary in making alterations in the mode of choosing the magistrates of the burgh, and to his interference at this epoch may be referred many of those evils which have resulted from the government of the city by self-elected functionaries.

In 1591, the citizens of Edinburgh had the merit of defeating an attempt of the Earl of Bothwell to seize the person of the king. That nobleman having been admitted at night into the court of the palace, advanced directly to the royal apartment; but happily, before he entered, the alarm was taken, and the doors shut. While he attempted to force open some of them, and to set fire to others, the citizens had time to run to arms, and he escaped with the utmost difficulty. Bothwell retired to the north, but eight of his followers were executed on the morrow. The assassination of the young Earl of Murray, the heir of the regent, by the Earl of Huntly at Dunnibristle, which, by the citizens, was referred to the will of the king, excited universal indignation in Edinburgh. The inhabitants rose in a tumultuous manner, and though they were restrained by the magistrates from any act of violence, they threw aside all respect for the king and his ministers, and openly insulted and threatened both. James, thinking it prudent to withdraw from such a storm, fixed his residence for some time at Glasgow. Other feelings afterwards arose, and the citizens testified their respect for their sovereign by sending ten tuns of wine, and a hundred citizens to attend the baptism of Prince Henry at Stirling, and afterwards by appointing him a guard of fifty citizens, to protect his person from the attempts of Bothwell.

In 1598, the boys of the High School, catching the contagion of the period, arose in rebellion against book and ferule, and transacted a scene somewhat similar to a modern English barring-out, but only a good deal more violent and fatal. On the magistrates attempting to reduce them to order, a boy fired a pistol through the door, and killed one of the bailies.

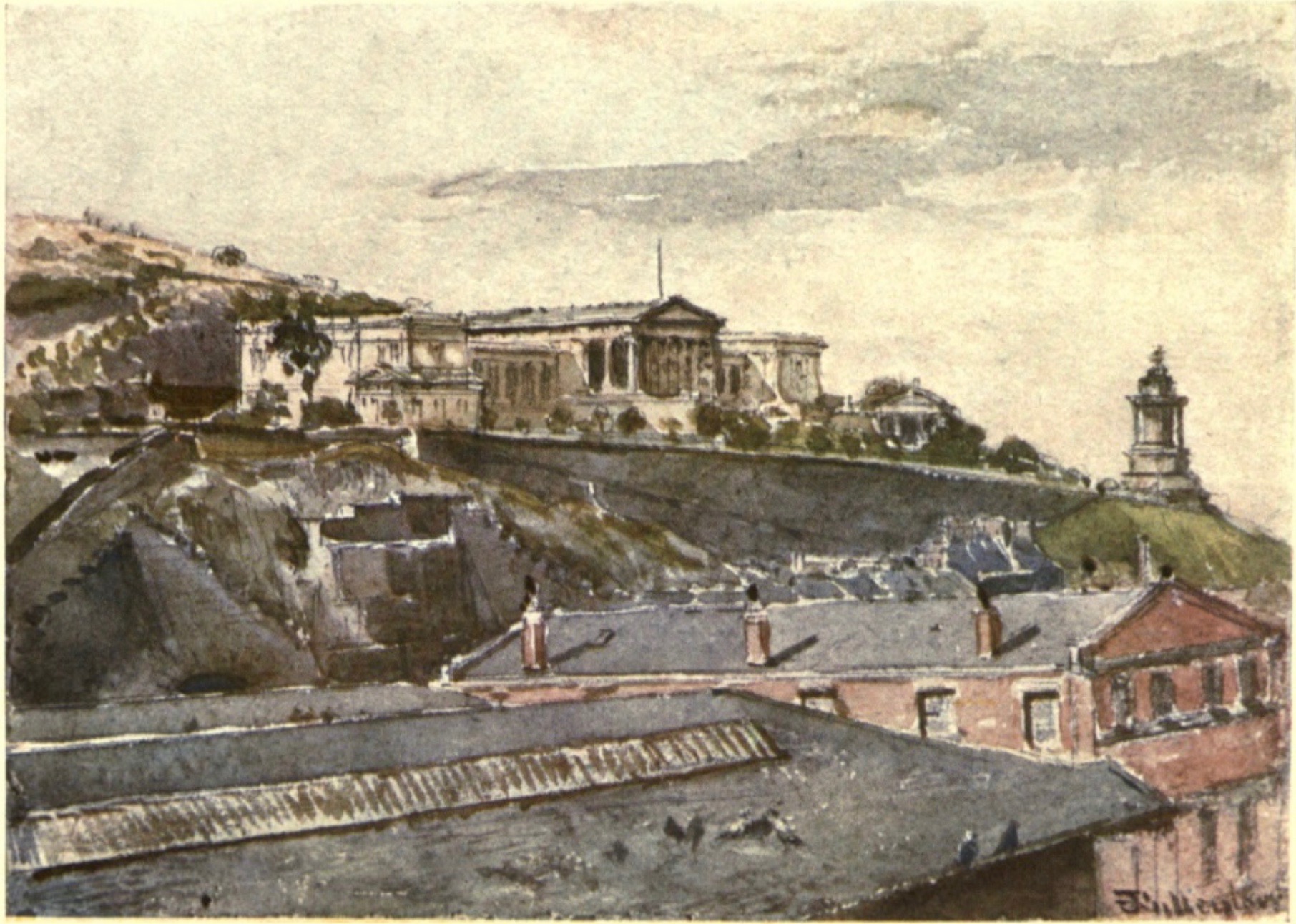

The High School and Burns’s Monument from Jeffrey Street by John Fulleylove, RI. (1907). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The most remarkable circumstance connected with the intercourse which obtained betwixt James and the town of Edinburgh, during the distractions of the times, was the alternate abuse and adulation the inhabitants heaped upon him. One day he fled for his life before their excited rage, and soon after a deputation would wait upon him to appease his wrath and purchase his return to good humour, which he was never long in conceding. More than this, the king was himself sometimes the first tc hold out terms for their return to favour. On the 19th of August, 1596, the queen was delivered of the princess Elizabeth, and the magistrates being invited on the 1st of December to attend the christening within Holyroodhouse, they promised to give this welcome princess a dowry of 10,000 merks on her nuptial day, which engagement they had actually the honour to fulfil, with an additional gift of other 5000 merks. In December, 1596, the clergy and citizens of Edinburgh, being wrought up to a state of extreme excitement, by an attempt on the part of King James to assert his control over the language of the pulpit, the furor broke out into a serious tumult, in the course of which the person of the king was not only insulted, but seriously threatened, though the whole affair afterwards ended without any violence. James, seeing that this gave him an advantage in the eyes of sober people, withdrew from the town, ordered all public courts to be removed from it> and seemed to have resolved upon procuring its complete destruction. But he was afterwards softened by the tears and cash of the magistrates, and induced to restore the city to his favour. In 1599, James had another dispute with the city clergy, on account of a band of English players which he introduced at Edinburgh, and which is supposed, not without good reason, to have included the illustrious Shakespeare. The presbytery of Edinburgh having passed a decree against them, was summoned before the privy council, and obliged to recant. This visit from the children of Thespis is a remarkable incident in the history of the city and country, for they were the first dramatists who had ventured to appear on a Scottish stage since the more quaint mimicries in vogue before the Reformation; and in their kindly reception by the people we are to trace the first signal of a return to the ordinary mirthful amusements of enlightened society.

The king did all in his power to dispel the gloom which had so long spread its blighting influence over the country, and we learn that at a convention held at Edinburgh on the 24th of June 1598, it was ordained that Monday in every week should be a play-day. The next year is remarkable in history for the change which was made in the manner of computing time. Hitherto the year was calculated as beginning on the the 25th day of March, agreeably to a very old usage, and hence the confusion which frequently occurs in speaking of transactions in Scottish history which occurred in the months of January, February, and March till the 25th day, which period of time has always to be referred to, as belonging to two years at once (as 1597-S). The Convention of Estates which met at Edinburgh on the 10th of December, 1599, remedied this evil, and, ordaining that new-year's--day should in future be the 1st of January, the year 1600 was opened in pursuance of such an arrangement.

In the Gowiy treason, which was developed in the month of August this year, Edinburgh had no share, except that its favourite clergyman, Mr. Robert Bruce, and several others, were brought to considerable trouble, on account of their scepticism as to the reaUty of the conspiracy. The bodies of the Earl of Gowry and his brother were beheaded and dismembered, on the High Street of Edinburgh, on the very same day when the illstarred Charles I. was born to King James at Dunfermline. When, called by the death of Elizabeth (March 24, 1603), to the throne of England, James took a formal farewell of the citizens of Edinburgh, who, through good report and bad report, had now been attached to his fortunes for twenty-four years. He addressed them in St. Giles' Church, after sermon, and it is said that when he concluded his speech, in which they seemed to hear native royalty speaking to them for the last time, they could not help melting into tears. Two days after, the king set out for England, the castle firing a volley at his departure.

At this period the city continued subject to the dreadful malady of the plague, which seems to have been long an occasional scourge of the inhabitants of this as well as other populous Scottish towns.

James was not forgetful of Edinburgh. In 1609 he empowered the magistrates to have a sword of state carried before them and to wear gowns; and, with his usual attention to trifles, he sent them patterns of those garments. There is reason to believe that these were the earliest magisterial robes which came into use in Scotland, as it is a certain fact that it was not till 1606 that the peers were required to appear in parliament in robes, which were of red cloth lined with white, "the like of which," says Birrel, "was never seen in this country before." We may, therefore, accept of these as among the first appearances of English state costumes in Scotland. It is probable that James sent offerings of this kind to Edinburgh, as much for the purpose of purchasing the good will of the town as for adding dignity to the functions of the magistrates. It appears that he was generally in debt to the city, and we find that in 1616, he committed a decided act of bankruptcy, by obliging the corporation to accept of twenty thousand, instead of fifty-nine thousand merks, which was the amount of his debt at that time. Such a circumstance, however, did not break up the friendship which had so long subsisted between the parties.

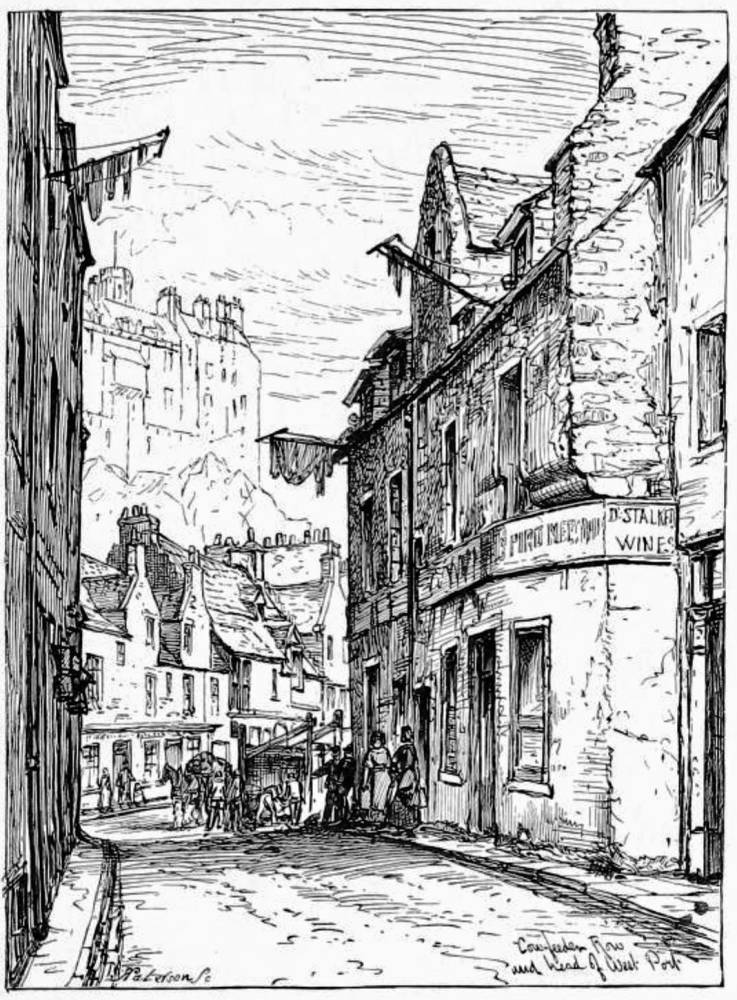

Cowfeeder Row and Head of West Port from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh. Click on image to enlarge it.

In the year immediately succeeding, the king paid his long promised visit to his native country, on which occasion he was received at the West Port, and conducted through the city with great pomp and demonstration of rejoicing, as well as by a speech of the most fulsome adulation, wherein, upon the "verie knees of their harts," he was described as "the perfection of eloquence," and "the quintessence of rulers." The citizens afterwards entertained the king with a sumptuous banquet, and presented him with ten thousand merks of double golden angels, in a silver basin. On the 28th of June 1617, James convened his twenty-second parliament at Edinburgh, by which some very remarkable acts were passed, and, among the rest, that for the restitution of archbishops, bishops, and chapters. The king presided at a scholastic disputation of the professors of Edinburgh University, at Stirling, and shortly afterwards returned to London. During the succeeding few years the Estates and town-council passed different acts for the improvement of the city, especially one in 1621, for the coping of houses with lead, slates, or tiles, instead of thatch, which, curious as the fact may now seem, had hitherto been the common covering of the lofty tenements of Edinburgh. Water was introduced by pipes the same year; and three new bells, two of which were for St. Giles' Church, and the third for the Netherbow Port, were imported from Campvere, in Holland.

James VI. died at London, on the 27th of March 1625, without having again visited his Scottish dominions, and, on the subsequent Sunday, the ministers of Edinburgh preached his funeral sermon, in which they praised him as the most religious and peaceable prince that this unworthy world had ever possessed.

Bibliography

Chambers, Robert. The Gazetterr of Scotland. Edinburgh: Blackie and Son, 1838. Internet Archive online version digitized with funding from National Library of Scotland. Web. 30 September 2018.

Last modified 1 October 2018w