'Navvies,' John Ward once said, 'are not, like Hodge, priest-ridden, for religion is a thing they know little of.' Navvies, said every Christian, are godless pagans heading headlong for damnation. Christendom's counter-attack came in two phases: pre-Navvy Mission Society missions, and the Navvy Mission Society itself. '

The problem with the pre-Society missions was they were unconnected and haphazard: even the heaviest dose of religion was no good if the navvy never saw a Christian again. For this reason they were pretty ineffective, in spite of the fact there were plenty of them. In the late '60s, four separate missions competed for navvies on the short Kettering-Manton line, where Daniel Barren was the Bishop of Peterborough's appointee. He had a seven-mile parish and three chapels with wooden belfries hung with bells which chimed, not tolled, and flagstaffs for flying the cross of St George on Sundays. He opened his mission to a congregation of forty-two — of whom only the odd two were navvies, and one of them was so drunk he had to be led away, protesting he'd heard it all before — in jail.

What the Society offered when it came was a continuity of effort, aim, and house-style. Like booking into an international hotel you always knew what to expect on an Navvy Mission Society job. The trouble, then, was navvies liked the amenities that were offered more than the religion that was preached.

I never heard any one say anything against the Navvy Mission. It was a blooming good thing. They were always preaching at you at dinner time, that was all. I didn't want no bugger preaching at me while I was eating my bit of snap.

Nor did they always like what was preached at them — a [200/201] Christianity stripped to its Jewish and Iranian origins, full of eastern demonology and the promise of pain to come. It was this threat of never-ending violence against the person that most offended navvies: violence against people who never asked to be created — to be set up and knocked down like coconuts in a cock-shy — and then be tortured with inhuman cruelty for trivial offences in a pitifully short life in which they were chiefly preoccupied with staying alive. It was a kind of terrorism: people were terrorised into being Christian. Except many weren't, and wouldn't be.

'Do you mean to say,' a navvy asked the Rev. Fayers, on the Lune valley line in the '50s, 'that arter working on these railways, enough to pull a feller's heart out, we'll be hard worked in the next world?'

'Yes,' said Fayers — and repeated it to Old Alice, a middle-aged woman (prematurely old) bright in lindsey petticoats. Old Alice didn't believe him, either.

'Why I goes about the country for the good of old England,' she argued, 'I puts up with all they put upon me, and when navvies slope me, I bears it all, and shan't go to a bad place.'

'Jesus says no one can get to heaven but by him,' Fayers argued back, 'and the reason you hope to get there does away with Him altogether.'

'Nowt o' sort,' snorted Old Alice, pretty sure hardship now ensured and easy hereafter.

Apart from anything else it grated against a sense of fair-play. Unfairness was bad enough on earth, in heaven it was intolerable. 'They certainly wonder', said one lay preacher, 'that God should have made some rich and some so dreadfully poor.' Yet some Christians like Katie Marsh seem to have had no concept of equality at all, not even in death. Miss Marsh lived in constant terror she was less holy than her mother who, in consequence, would be graded so much higher than her in heaven's hierarchy they'd never meet again in all eternity.

Most navvies, as well, disliked parsons. How could leaning on a pulpit twice a week pay better than shifting two hundred and fifty tons of muck? 'Many of them regard a clergyman as their natural foe,' said the Rev. Munby, vicar of Turvey, in the early '70s. 'Once, I heard a party of them say: "Look, here comes the parson. Let's heave a truck at him.'" In return many parsons disliked them. 'Too bad to go among,' said a> Baptist minister. 'Not an atom's worth of honesty among them,' said the Rev Thompson, missionary on the South Devon [201/202] line, 1840s. 'Vile and immoral characters,' intoned the Rev Sargent, missionary on the Carlisle-Lancaster, also in the '40s. Navvies, on the other hand, were much more open to parsons' wives and daughters, untouchable in muck-long frocks, not unlike pedestals. In return, by accepting them, those wives and daughters made navvies more acceptable to society by changing people's perceptions of them. And a sense of acceptance by society must have made the navvy more receptive to society's religion.

Pre-Navvy Mission Society, there was Anna Tregelles (whose book, Ways of the Line, inspired the nameless authoress of Life or Death) and, above all, Katie Marsh. Contemporary with the Mission there was Elizabeth Garnett and the dozens of women who did the Society's donkey-work — from not-quite-gentlewomen like Katherine Sleight to bluebloods like the Countess of Harewood. Supreme among them, the navvy's arch-friends, were Katie Marsh and Elizabeth Garnett. Miss Marsh never married and though Mrs Garnett obviously did, her husband died on their honeymoon soon after her wedding. Both were daughters of> Anglican clergymen.

Katie Marsh, born in 1818 in Colchester, was always unintimidated by the great, accustomed as she was to the illustrious of the land through her father's connections, by marriage, with the nobility. She had, she said, no politics (just anti-Gordon-ics and anti-Bradlaugh-ics) though that didn't stop her telling Mr Gladstone to defy the electorate of Northampton and throw Bradlaugh out of Parliament. 'Save our country from the Apostle of> Atheism,' she told him.

At first she seemed an ordinary spinster-daughter of the parsonage and it was the shock of being thirty that turned her into one of the foremost evangelists of her day, influential both in Britain and the USA. Navvies were only a brief bit of her life: she knew them only when they came to re-erect the Crystal Palace near her father's parish of Beckenham and later when the Army Works Corps was drafted from there to the Crimea. By then she was in her late thirties, plump and plain, not unlike the later Victoria, with ballooning frocks and ballooning face.

Beckenham Rectory, a small mansion set in lawns dotted with disc-like flower beds, overlooked the rural hills of Norwood. Beckenham itself, still a village, housed some of the Crystal Palace navvies. Miss Marsh first met them one Sunday evening in March 1853, on the pretext of seeing a sick parishioner. [202/203]

'Harry ain't here now,' said the navvy who opened the door.

Could she wait?

'Well, you can if you like,' said the man, 'but we're a lot of rough uns.

'I don't mind that,' said Miss Marsh.

Nobody, least of all ladies tea-cosied in crinolines, spoke to navvies like that. Navvies were brutish half-men looming on the edges of mankind. The prognathous jaw that bit. The impact of her book about them, English Hearts and English Hands, was the greater because of her refinement and femininity (the impact of a book by a professional Christian, a clergyman in a stove-pipe hat, would have been that much weaker). From her book it was clear navvies were not Neandertals without the body hair: they were kind and manly, shy and simple (too ill-educated to be politicised like artisans), guileless but beguiling. Her book was a major navvy turning point. A turning point for others, too: Aggie Weston, foundress of the Sailors' Homes, admitted the book inspired her to begin her work for the Royal Navy.

Elizabeth Hart, later Mrs Garnett, was born at Otley in Yorkshire in 1839. Mr Hart, like Mr Marsh, was a vicar but more poorly connected. Where Miss Marsh spoke to most of the English-speaking world, Elizabeth Hart spoke mainly to navvies; where Miss Marsh scolded Prime Ministers, Mrs Garnett scorned the socialists of the Navvies' Union. Elizabeth Hart (Mrs Garnett) was a natural-born organiser, unasked, of other people's lives. If her husband, a clergyman, hadn't died on their honeymoon she would without a doubt have terrorised some hapless parish into Christianity through unbending good example and unending chiding. A small, strong-jawed, strong-willed woman; irrefragable; strong with the robustness of simplicity: the world's complexities always puzzled her.

Laws, she thought, were quite literally based on the laws of Christ yet it was awful to see, every day, his laws superseded by men's. 'Look at the newspapers', she would say, 'and they are full of disagreements and strikes, and quarrelling, everyone trying to get all for themselves. Men think everything can be done by law, and so they make laws until they law away all an Englishman's self-responsibility and freedom.'

Strife distressed her. Why must people argue when Christ instructed them to be friends ? 'Dear Friends,' she pleaded, 'do let us 203/204 navvies stick together, and be pleasant to one another. Give your contractors a civil bow. It's a very heavy burden to plan how to get you work to pay your wages. You know how hard many of these men's lives are,' she went on, turning to the contractors. 'Think for them. See there's plenty of skilly, and a dry cabin with a good tea-can stove for wet weather, and spin out the work in winter.' But if she was disingenuous she was also open-hearted with a deep abiding affection for these big and wayward men. She was genuinely appalled at their sightlessness in endangering their souls. How could men care so little for eternity, they wouldn't lace their boots to walk half a mile to be saved? So she hectored, scolded, nagged and bullied them. At times she sounded like a schoolmistress in charge of an unaccountably drunken hockey team; but she never looked down on them and her loyalty to them never slackened.

'We trust that you will feel when you receive this,' she told them in the first issue of the Letter, 'there are those in the world who love you still. Hitherto, as a class, the Navvies have not been duly cared for. That day is past.'

She was often — she was usually — indignant at their conduct and always shocked at any lack of pride in a navvy's calling. She called them 'mates'. She called herself a 'navvy'. They were her entire life.

I was for many years,' she said in 1898, 'the unpaid clerk. Librarian, Editor, Drawing Room Speaker, etc, besides being one of the Committee and Managers of the Society. I have never been paid one penny,' she went on, 'and if ever I get so poor that I have to be paid, it will be "good-bye" and you will not see me again. No, I will work for the love of Christ, and for the love of you, or not at all.'

To many she was the Mission: the one person they really knew (apart from the missionaries) because for nearly forty years she nagged them endlessly in the Letter, the Society's official magazine, which she edited all that time.

Until 1893 it was, more properly, the Quarterly Letter to Navvies/rom the Navvy Mission Society. That year Men on Public Works was substituted for Navvies in accordance with the new reality. Navvies now shared public works with black-gang men and other trades, all in need of saving. It was a small green-backed pamphlet only ever called the Letter, Navvies' Letter, Quarterly Letter or the Green 'Un. Its colophon was a diamond shape made of a round-nosed shovel, a pick, an axe, a saw, and a pan, with an open Bible in the middle. At first its bold lettering — of which there was a [204/205] lot: it was an emphatic publication — was in a heavy square-serif Wild West typeface which gradually thinned down as the magazine matured.

Mrs Garnett always suspected people read it, like the Chinese, from back to front. At the back were the endless lists of dead and injured and the scandal sheet: who'd eloped with whom, who'd sloped who, who'd gone missing, whose children were in the workhouse. At the front was the epistle-like 'letter' itself, often from Mrs Garnett, often from a guest writer. It was always uplifting. Drink was its big theme ('How many bundles of meat have the Bobbies walked off with this summer?' Mrs Garnett wondered in 1881, deploring another year of drunkenness) and it frequently carried moral tales, dreadful warnings, true-life confessions and recipes for cooling drinks for alcoholics wanting to dry out. In its summer 1903, edition it told the tale of a drunkard who cut his throat. He lay on his back, a look of dumb craving in his eyes, as his friends and relatives crowded round his death bed. "Do you want a minister?" asked the doctor. The man shook his head.'

' "Would you like a prayer said?" He moved his lips but no sound came. He was dying fast, and they could not make out his dying wish. The doctor stooped and put his ear down to the man's mouth, but he could not hear what he said. At last the man took his fingers and fairly pinched the wound close, and feebly said, "Doctor, for Christ's sake, give me another glass.'"

Then there was W-P-, a drunkard who died of drink. The autopsy showed his heart weighed only two ounces instead of eight. 'It was dried up with that stuff called whiskey. I thank my God He has kept me from the cursed cup.'

The Letter also printed what must be history's least sung anti-booze ballad, so appalling it could only damage sobriety's reputation. (To make it worse it was written by a Scot but attributed in the chorus to an Englishman.) It went to the tune "The Days We Went A-Gipsying":

Chorus:

Yes, I am an English navvy, but, oh, not an English sot,

I have run my pick through alcohol, in bottle, glass, or pot,

And with the spade of abstinence, and all the power I can,

I am spreading out a better road for every working man.

Sometimes they printed useful hints, like how to stop bleeding. On [205/206] the covers were the job lists that were, in fact, the navvy's best source of information about new jobs, old jobs, and where to tramp to next. These alone would have meant the Letter was widely read and its print runs were always high — 155,000 copies of one issue in 1904, its highest ever. Even at the outbreak of the Great War editions ran to a hundred thousand.

Mrs Garnett's involvement with the Mission was an accident of time and place which brought her, free and uncommitted, to the Lindley Wood dam where and when it began. She first saw the place one Saturday evening after dark in the fall of '71, when it was already cold with the coming winter. The gutter trench was being sunk, lit by the glare of the pumping engine fires. Feeble lights shone from the huts a mile or so away. The shingled church with its high pitched roof stood in a clearing in the woods above them. She thought she might be in Canada. It was a place she could never forget; the red huts in the sun, she remembered, and the wood itself blue with harebells.

The Mission was not yet founded though its founder, the Rev Lewis Moules Evans, was already at work at Lindley, already ill with tuberculosis, and the idea for it had already been given him by a navvy he met in a third-class railway carriage somewhere in the north of England.

'Outlaws, sir,' the navvy told him, 'that's what we are. Wanderers on the face of the earth, and outcasts from society. Decemberent people, them as lives in towns and villages and has homes of their own and no occasion to tramp, they gets a notion into their heads as we belongs to a different breed from what they do. They reckons us a sort of big strong beasts, very useful in our way, but terrible dangerous and not of much account except for strength.'

'Why, it was only t'other day as I heard a woman telling about a railway accident, and she said as there was three men killed and a navvy. We ain't men at all, we ain't got no feelings nor no souls, nor nothing but just strong backs and arms and a big swallow for beer.' — A common story. A twentieth-century version is set in a pub in Wales: 'Who's that coming down the mountain, landlord?' 'Two men and a navvy.'

He was middle-aged, middle-height, a man who'd been a navvy since he ran away from home as a boy. For years he'd been as roving, drunk and dissolute as the rest. Then one Christmas a year [206/207] or so ago he was dropping down through woods off the Yorkshire moors, on tramp and lost. Ahead of him through the trees he saw yellow candlelight spilling on the snow and he heard singing. A ramshackle chapel filled with navvies. He went in, glad to rest in its warmth, drowsy and half-listening until the clergyman said something that transformed his life. 'What he said sounded so strange and new to me,' said the navvy, years later in the third class railway carriage. 'He told us about the Saviour who came at Christmas time, all out of love for us: and he made it plain he meant us. I felt as if I'd found some one who cared for me.' The feeling transformed his life. He learned to read — he pulled a Bible and prayer book from his pocket — though still at times he was afraid. Places like that chapel were rare. 'What we want is more work like that,' he said. 'Regular work. We're most of us very ignorant, and it isn't likely as we can teach ourselves and we want some one to come to us and teach us.'

Around this time Evans was given the living of Leathley, a hamlet in the Washbourn valley where the Lindley Wood dam was being built for Leeds Corporation. Evans used to walk alongside the stream to the dam through the birches, oaks, foxgloves and bracken of Lindley Wood. He called himself a navvy — 'I work on public works.'

'I've come three miles to tell you something that will do you good,' he once told a navvv. 'Won't you come a few yards to hear it?'

'You see, sir, I've not got a hat,' said the man. 'It's not respectable to go to a place of worship bareheaded: now if I'd a tile . . . '

'Then here's mine.'

'Nay, put your hat on, sir. I'll come as I am.'

'I want you,' Evans told them, 'Not your jackets. Come just as you are.' Though he added, 'You need only leave your pipes behind.'

The Christian Excavators' Union, which predated the Mission, was also founded around this time at Lindley Wood. It was open only to working navvies, who wrote the rules.

'I desire by God's help,' aspirants testified, 'to serve the Lord Jesus Christ, and to lead others to do so.'

'To this end.'

'I promise to abstain from drink, swearing and ungodly living.'

'I promise never to neglect praying each morning and night.'

'I promise to keep the Lord's Day Holy and when possible to [207/208] attend a place of public worship.'

Each man had three months to clear his debts, prove himself, and make himself ready before he was accepted. Each carried a card and, after 1883, a badge (two hands clasped over a Bible) proclaiming his intentions. With it went the blue ribbon of temperance and the white ribbon of purity. Mrs Garnett always said they were the salt for Christ on public works. The Navvy's Guide said they were spies.

The Christian Excavators' Union began with thirty-seven members, rose to about three hundred in the early '80s and peaked at nearly seven hundred in 1913. By 1916 they were down to just over eighty. The War took a lot of them, old age the rest.

Evans must have had the Mission in mind for some time though he did nothing about it until the dam was nearly finished. Then he began with a market survey, in 1875. Questionnaires were sent to most of the public works he knew about. How many worked there ? How many churches? How many clergymen visited them? How many Sunday schools? How many day schools? Less than half the engineers answered but from those who did Evans calculated there were about forty thousand navvies in England. With women and children that probably meant a total of between fifty and sixty thousand people. Only three jobs had a child's day school, three had a night school, only one had a Sunday school.

Evans, already dying of tuberculosis, sheltered in Italy in the winter of 1874-5, before writing an article — "Navvies and Their Needs" — for the religious weekly, The Quiver, asking for help in setting up a Mission. This he followed with a leaflet, also called Navvies and Their Needs. 'Navvies,' it began, 'form a class by themselves, isolated: First, by the nature of their work, which is often carried on in places remote from towns or even villages. Secondly by their roving habits: and Thirdly by the belief, which commonly prevails among them, that they are looked upon as outcasts.' These were the key insights on which he built the working philosophy of the Mission. More important (initially) than being taught religion, navvies had to be taught they belonged. The roaring and the uproar had to stop. They had to quieten down to listen. For that they had to have more in their lives than drink and work. Evans proposed giving them drink-free mission rooms and night schools where they could learn to read and write, then libraries for when [208/209] they could. (And not just religious books either. Geology, unsurprisingly, was popular. Once the Mission was running properly Mrs Garnett sent whole 250-volume libraries, complete and catalogued, to most public works which had a missionary.)

It was to be a kind of nursing, a kind of therapy. But since the navvy moved too fast to give it time to work, the therapy had to be waiting for him wherever he went. What was wanted were mobile missions and nimble missionaries to meet the fleeing heathen wherever he ran.

Towards the end of 1877, Evans followed Navvies and Their Needs (article and leaflet) with a flurry of hand-written and printed appeals and within a few weeks — probably in November — he was able to set up his new Society formally, with himself as its first Secretary and the Bishop of Ripon on its first committee. By the summer of 1878 Evans, no longer coughing up dark blood, was fit enough to travel to the dams at Cheltenham, Denshaw, Fewston, and Barden Moor, fixing the society physically on the ground. Early that autumn he was even fit enough to make the sea-crossing to the Isle of Man Railway where, in spite of the sea, in spite of mountain air, soft dark gouts of blood began welling up into his mouth again, leaving him pallid and enfeebled, too weak to speak at that year's Church Congress in Sheffield. The Dean of Ripon spoke for him.

'Navvies are looked upon with suspicion,' the Dean told Congress, 'and are treated as if they were the wildest and the worst of beings — the poachers, the drunkards, the Sabbath-breakers, the brawlers and blasphemers, the adulterers, and heathen of the district. Thus a bad name is given to them, which they reciprocate, and keep themselves to themselves.'

Evans told everybody else — whatever he told himself — his lungs were sound and getting better. All he had to do was keep clear of damp. In November, which was both cold and clammy, he insisted on travelling to a Christian Excavators' Union meeting in Ripon and on the way home he had to wait in the cold on Otley railway station, pacing about in the oil-lit darkness, breathing wet Yorkshire air. As soon as he could he saw a doctor, afterwards telling his friends he was still on the mend. He died suddenly early in Decemberember and they buried him in his own graveyard, followed by mourning navvies. He was thirty-two. But his society was safely founded in spite of the contractors, engineers and city corporations who wished it wasn't. 'Of an evening the men should be in bed,' said one engineer. 'They are [209/210] better without reading.' 'Again and again,' Mrs Garnett recalled, years later,

we were refused even a bare old building for a day school (even though a friend was responsible for all expense) and we showed them the School Board Schools (just started) and the Parochial Schools both refused to admit our children on account of the room limit. It was hard to bear. Insults are not pleasant to the flesh, wrong motives were imputed and on all sides suspicion, and derision our portion, but if a work be God's, it will go on.

And go on it did. Within a year or so the Mission had its own house-style that lasted to the end. You always knew what to expect on a Mission job: a lay missionary (preferably ex-navvy) and a mission room, a library, a room to smoke and read in; schools for children; bible readings, concerts, tea parties and meat teas. The missionary, as well, was ready-made to run Sick Clubs, savings schemes, first aid and even violin classes.

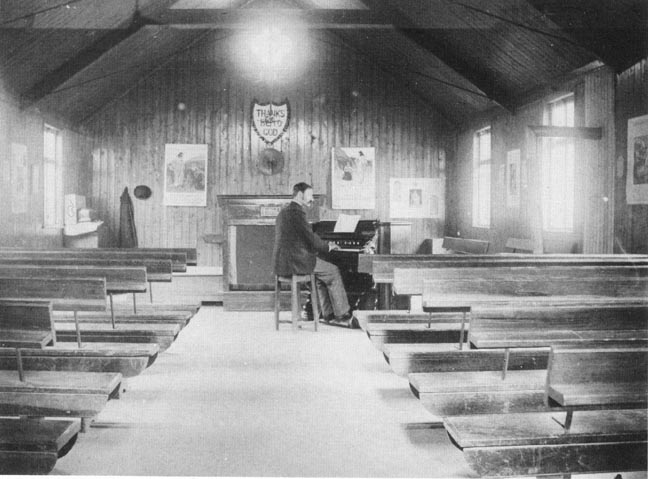

Navvy Mission Room. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Everything centred on the Mission Rooms: wooden huts furnished with wooden pews and harmoniums, heated in winter by iron stoves with long thin flues. In place of altars there were wooden pulpits draped with cloths embroidered with the Navvy Mission Society's entwined initials. On the walls were posters: 'Dedicating the Temple', 'Christ at the Feast', 'The Gracious Call'. Gothic-lettered texts read: 'By grace are ye saved', 'Learn from me for I am meek and lowly in heart', 'Seek ye first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness'. [At least one mission hut survived, at least until 1980, at Hutton Roof on the Thirlmere pipe track of the north Lancashire fells. Until 1980, it was the Village Hall.]

To the Victorians the Mission was eminently worthy. It listed the Primate among its patrons, as well as the Archbishop of York, most of the English bench of bishops and sundry Lords and gentry. No navvy, however, sat on its committee and only one woman ever did: Mrs Garnett. Yet in spite of the male upper classes on top, at the bottom it was run by women and working men. The Society, essentially, was a loose collection of local Navvy Mission Associations coordinated from a central office. For many years this was wherever the Secretary lived — Ripon sometimes, Leeds and Warrington at others — until the Society took permanent desk space in the cellar of Church House, in the quad next to Westminster Abbey (image), in 1893. The central office, mobile or fixed, paid only a third of any mission's costs, and a third of every [210/211] missionary's eighty pounds a year wages: the rest was found locally by the local Navvy Mission Association — by cajoling contractors and city corporations, through public subscriptions and drawing room fund raisings. It was here middle-class women were pre-eminent.

Katherine Sleight, at first, was typical: a widow of private means attracted to the Mission when the Hull-Barnsley railway came near her home in Newint. She busied herself on the new Hull dock and railway, handling the Distress Fund in the hard times. She became a-typical when the loss of her private income made her take a salaried job as the Society's Association Secretary in London. She did well — doubling the number of bodies associated with the Mission, opening a fund to pay the wages of a nurse on the Thirlmere dam — but in time she got very fat and her feet became agonisingly tender (often she had to stop in the street and change her outdoor boots for carpet slippers.) On Christmas Eve 1897, she took to her bed clearly dying of dropsy and heart and liver disease. Beef tea, milk and oysters were all she could swallow and the swelling of her limbs grew grotesque. Finally her mind gave way and she thought she was back in Hull talking to her dead mother. She died in 1898, aged forty-six.

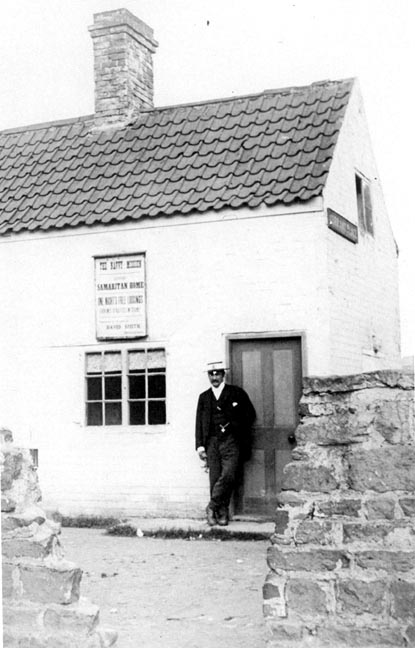

Left: Navvy Mission Room and Missionary. Right: Navvy Smith

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

Missionaries were black-suited, white-shirted, dark-tied working men who in summer wore straw boaters with a dove of peace badge pinned to the hat band. The whole Society, naturally in Victorian England, was very class-biased and once the navvy swapped his moleskin for semi-broadcloth he crossed into another lonely life. The navvies he left distrusted him as one of the others: the others refused to accept him as one of them. Ordination — self-betterment by class-hopping — was discouraged. David Smith was typical.

As a missionary he was nicknamed Navvy Smith and later — to his evident disgruntlement — Daddy Smith. He was born in 1866 in Newhaven, Sussex, where his father, a smith by trade as well as name, sub-contracted the iron-work in the new harbour. From Newhaven the family moved to Bristol where docks were building at Portishead, Shirehampton, and Avonmouth. Navvy Smith started work there, carrying bricks at the bottle works, and then carrying mason's tools to and from the blacksmith's shop on the New Dock. Navvy Smith, born in the '60s, became a Christian in the 70s, a smith in the '80s, a missionary in the '90s. In 1888 he was smithing on the Ship Canal when he met the Rev Robert Grimston, the [211/212] Canal's chaplain (later the Mission's Secretary), and the man who did more to alter his life than anybody else save William Perry, a squire's gardener near Bristol, who first converted him to Christianity. At the time he met Grimston, Smith was pushing an injured man home in a wheelbarrow. Grimston offered an unusually ineffectual hand before going off, more usefully, to commandeer a locomotive. Later, Navvy Smith became one of his missionaries on the Great Central, running the Good Samaritan Home for tramp navvies at Bulwell, north of Nottingham.

After that Navvy Smith ran missions at the Catcleugh dam in Northumberland, the Privett tunnel in Hampshire, at Sodbury tunnel, at Shirehampton docks and finally in 1906 and for the next twenty years in Birmingham. For four years until the War closed it in 1916 he was joint-editor of the Public Works Magazine (a missionary-level version of the Letter, as far as we can tell).

Tom Cleverley (sometimes spelled — and presumably pronounced — Cleaverley) was born a navvy at Penarth docks in 1855. For ten years or so he wandered about the country working first as a nipper then a full-blown navvy on railways, docks and dams until finally, all unknowingly, he wandered into the Lindley Wood settlement and a different way of living.

'In those days,' said Mrs Garnett, 'Sunday was called Hair-cutting and Dog-washing Day — hair cutting in the morning, dog washing in the afternoon, and a free fight in the evening.' One Sunday she met Tom Cleverley, at Lindley Wood, taking his dog for a walk. 'Now, Tom,' said she to him, 'will you come to the Bible class?'

'No,' said Tom, 'I'm going for a walk with my little dog.'

'I believe you care more for that dog than for your own soul,' Mrs Garnett told him.

For Tom Cleverley that was the turning point of his life. He went to the Bible class, became a Christian, then a missionary. As a missionary he worked at the Cheltenham dam, on the Oxted-Groomsbridge, on the Ship Canal, and on the Great Central. Within a couple of years of its founding the Society had twenty-one full-time missionaries, a figure which went up to fifty-four by the century's end. Numbers then steadied at fifty-three before dropping to forty in 1915.

The Society was always tremulous for success and counted wins and losses in a curiously actuarial way — lotting up lists of statistics about the number of people going to Bible classes, prayer meetings, [212/213] confirmations, and Sunday services. But if simple arithmetic tells us little, how effective was the Mission? To begin with the police always vouched for Mission jobs. Crime dropped when missionaries turned up. The Mayor of Ludlow even put a figure on it: police court cases were cut by two-thirds when the Mission opened on the Elan pipe track. Christianity didn't break out spectacularly — it didn't throughout the country — but most people on public works were Christian, in a confused non-sectarian way, in the end. Navvies were christianised, if not churched. 'Looking back over fifty years what changes one can see,' said Navvy Smith, in 1923.

The navvy is a far more sober man today; he is better dressed, better educated, takes a keener interest in his social well-being and enjoys a status in human society which he never thought of years ago. Who will deny that this is the outcome of Christianity and Labour marching hand in hand? [213/214]

Last modified 25 April 2006