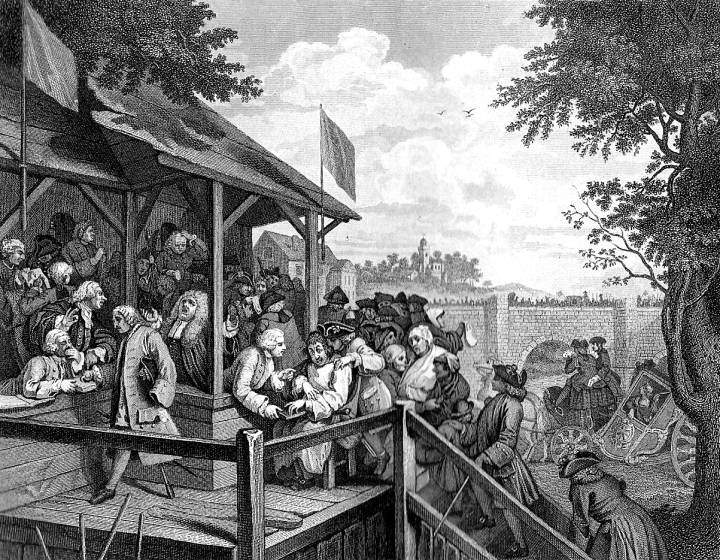

The Election (Part 3. “The Polling”) drawn by William Hogarth (1697-1764) and engraved by T. E. Nicholson. Source: Complete Works facing p. 126. Scanned image and caption by Philip V. Allingham [This image may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose.]

Hogarth's four paintings pillory the much vaunted electoral system, the cornerstone of the parliamentary democracy of Great Britain, by exposing such matters as party violence, bribery, and corruption in the electoral practices, especially prior to the establishment of "Election Committees" under the terms of the Grenville Act (1770). The system of eighteenth-century England, the product of the Glorious Revolution and the defenestration of absolutist King James the Second (Stuart) of 1688, was hardly based on universal suffrage. Women, of course, could not vote, but neither could the majority of British subjects. The British voter was either a "freeman" or a "burgess," each of whom could meet the property qualification of ten pounds. Vote buying was common enough: Sykes and Rumbold, for example, were fined and imprisoned for bribery during the 1696 parliamentary elections, and an elector of Durham in 1803 was fined 500 pounds. Even as late as 1840, voting irregularities compelled the authorities to declare the elections for Cambridge and Ludlow void.

According to Trusler & Roberts,

Previous to the publication of this series, Mr. Hogarth's satire was generally aimed at the follies and vices of individuals. He has here ventured to dip his pencil in the ocean of politics, and delineated the corrupt and venal conduct of our electors in the choice of their representatives. That these four plates display a picture in any degree applicable to the present times [i. e., after the Great Reform Bill of 1832] cannot be expected; but they are fine satires on times gone by, when the people of Great Britain were so far from being influenced by a reverence for public virtue, that they began to suspect it had no existence. [Trusler & Roberts, 128]

In the tenth chapter of Civilisation, "The Smile of Reason," in articulating the differences between English and French society in the eighteenth century Kenneth Clark argues that the works of William Hogarth exemplify the contentious and predominantly masculine urban society of eighteenth-century England: "Plenty of animal spirits, but not what we could, by any stretch, call civilisation" (250). To make his point, Clark briefly analyzes two well-known works by Hogarth, the print entitled somewhat ironically "A Modern Midnight Conversation" and the third and fourth paintings in the Election series, "The Polling" and "Chairing the Candidate." Although more succinctly than Trusler and Roberts a century earlier, Clark points out many of the socio-political elements that satirist depicts in loving detail, even though he hates the abuses he thus dramatizes. Whereas in the third scene, "The Polling," Hogarth scoffs at the notion of "independent" voting as one of the candidates (seated at the back, already anticipating losing to his complacent opposite) apprehensively shudders at the massive expenditure involved in his campaign, especially in buying votes, while the parade of "qualified electors" crowds the polling station: Hogarth by implication praises the faithful servant of his nation, the mutilated old soldier who is being sworn in by the clerk, while exposing the incompetency of the other voters, who include a deaf idiot, a man in fetters (a madman instructed how to vote by the keeper leaning over his shoulder), and an imbecile, wrapped in a blanket and transported to the polling booth by two attendants. Whereas the satire in the third plate involves the low calibre of the unlettered and undiscerning electorate, "imbeciles and moribunds being persuaded to make their marks" (Clark 249), in the final scene Hogarth celebrates the atavistic forces unleashed by the election victory:

We see the successful candidate, like a fat, powdered capon, borne in triumph by his bruisers, who are still carrying on their private feuds; and I must confess that Hogarth conquers my prejudice by the figure of the blind fiddler, a real stroke of the imagination outside the usual range of his moralising journalism. [249]

Bibliography

Complete works of William Hogarth ; in a series of one hundred and fifty superb engravings on steel, from the original pictures / with an introductory essay by James Hannay, and descriptive letterpress, by the Rev. J. Trusler and E.F. Roberts. London and New York: London Printing and Publishing Co., c.1870.

Last modified 20 March 2010