[These images may be used without permission for any scholarly or educational purpose without prior permission as long as you credit the Hathitrust Digital Archive and the Duke University Library and link to the the Victorian Web in a web document or cite it in a print one — George P. Landow ]

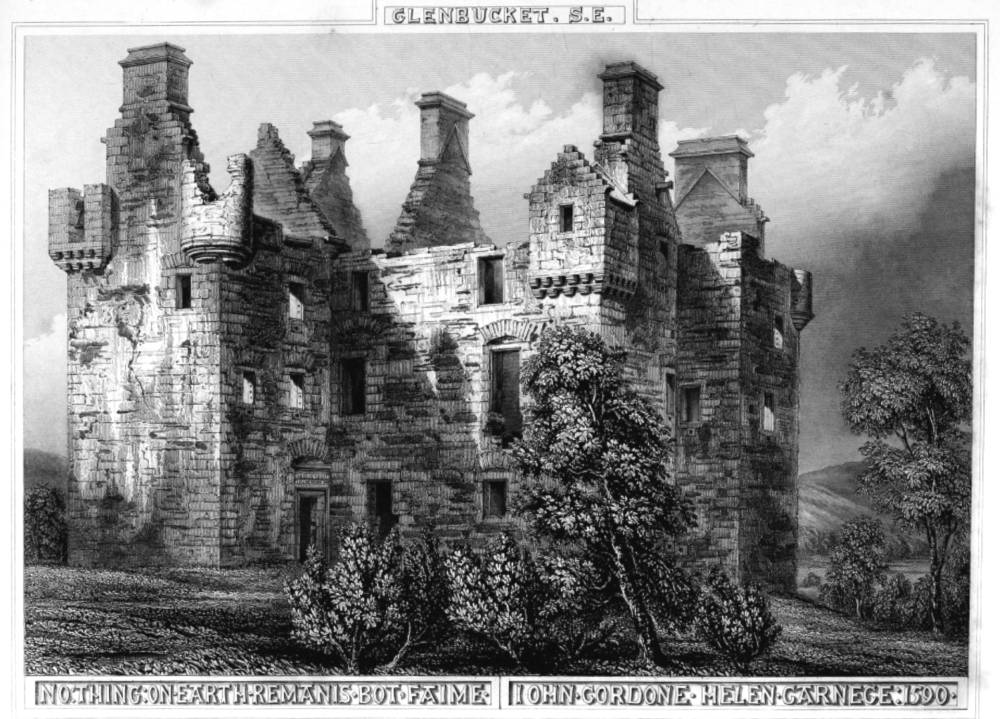

Glenbucket Castle drawn by Robert William Billings (1814-1874) and engraved by G. B. Smith. Source: The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1852). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Commentary by the Artist

As on the banks of the Dee, so along the nearly parallel vale of the Don, a line of fortresses passed from the centre of the mountain districts into the Lowlands, the upper department of them sheltering the "rievers" who plundered other people's fields, those in the low country serving to protect the fields of their owners, and some of them perhaps merging into both characters. "From Kildrummie," says the New Statistical Account,

to the head of Strathdon, there is a regular chain of ruinous castles; and it is a singular coincidence that the first four are all placed at equal intervening distances— Towie Castle being about three miles up the Don from Kildrummy; Glenbucket three above Towie; and Culquhanny three miles farther up than Glenbucket: a mile beyond Culquhanny stands the Douno of Invernochty; and lastly, at the head of the strath, the Castle of CorgarfF. [Letters from a Gentleman in the North, II, 73-75]

The last, now a comparatively modern barrack, is the scene of that frightful tragedy of feudal vengeance, so pathetically detailed in the ballad of "Adam o' Gordon," in which the daughter of Campbell of Calder, and her children and servants, were burned to death by Gordon of Auchendoun. The scenery on the Don is not so inviting as that on the Dee; and hence, while the greater part of the southern line of fortahces have been converted into pleasant dwellings, those along the other valley have been left to the care of the elements, and stand up from the bluff banks and wild brown moors, such ragged masses as the accompanying plate presents. The branch of Gordons who inhabited this distant fortress led a wild semi-freebooters' life, and but slight record would be preserved of their history. The inscription over the door, which has been fac-similed, probably contains the date of the earliest part of the building — 1590. Of this inscription it may be remarked, that the word "faime" which might give a mysteriously ambitious tone to the sentiment, "Nothing on arth remanis bot faime," is not intended to mean celebrity, but the humbler attribute of good repute. It embodies the sentiment expressed by Francis I. after his defeat at Pavia, but whether it was suggested by any similar event, must remain a mystery.

While the castle and its earlier owners have been unknown to the fame which its founder may be interpreted to have courted, the ecclesiastical records of the North, in connexion with the parish of Glenbucket, bear a curious testimony to the wild remoteness of the district, and the zeal with which the church carried its operations into highland wildernesses. In the year 1470, there is a deed of erection by the Bishop of Aberdeen of a church in "Glenbuchat," on the ground that, in proceeding to the proper parochial church at Logy, great perils are undergone by the pious parishioners, in fording impetuous torrents, and crossing wide bleak hills; and it is specially mentioned that, qn one occasion, five or six persons, proceeding to the celebration of Easter, perished of the hardships they suffered on the mountain track. It was made a very strict condition, that the clergyman should be resident; and as it seemed to be supposed that no one would remain true to that wild district, who could have any opportunity of living elsewhere, the chaplain who served at the newly erected church was prohibited from holding any other ecclesiastical endowment (Registrum Episcopatus Abredonesis, I, 308-09).

The estate of Glenbucket became known, along with some other territorial patronymics of a like uncouth character, during the Jacobite outbreaks of 1715 and 1745. The Laird of Glenbucket was a feudatory of the Earl of Mar, and had his rude fortalice very near the centre of the Earl's domains. It would depend entirely on the turn taken by intrigues in London, about which the Laird of Glenbucket knew no more than he did of tbe politics of the court of Cathay, whether he should be called out to fight for King George or King James. The latter was decided on, and the sturdy laird, having once taken his position, stuck to it. He was present, at the head of the Gordons, in the victorious part of the Jacobite army at the battle of Falkirk, and was all along conspicuous among the Highland leaders in that war. He kept his Jacobite feelings warm for thirty years, and heartily joined the standard of the Prince, unborn in his days of military leadership, who made the descent on Scotland in 1745. He was one of the few men of mark who escaped the vengeance of the successful party on both occasions, escaping to France in 1746. Not having been among those who had to feed the popular appetite for vengeance, and deliver a dying declaration on the scaffold, he has no place among the Jacobite biographies; but his name was so formidable, that, according to tradition, George II. used to start from disturbed dreams, in efforts to pronounce the name of Glenbucket, accompanied by exclamations of terror. An anecdote of this old hero, not generally known, is told by the gossiping Captain Burt, as an instance of clan jealousy. He had acquired a right, by the sort of security called a wadset, to some lands in the Macpherson country. The tenants troubled not themselves about parchment rights, but, knowing he was no Macpherson, declined to pay him any rent or service. "This refusal," says Burt,

put him upon the means to eject them by law ; whereupon the tenants came to a resolution to put an end to his suit and new settlement in the manner following: — Five or six of them, young fellows, the sons of gentlemen, entered the door of his hut, and in fawning words told him they were sorry any dispute had happened ; that they were then resolved to acknowledge him as their immediate landlord, and would regularly pay him their rent; at the same time they begged he would withdraw his process, and they hoped they should he agreeable to him in the future. All this while they were almost imperceptibly drawing nearer and nearer to his bedside, on which he was sitting, in order to prevent his defending himself, (as they knew him to be a man of distinguished courage,) and then fell suddenly on him with their dirks and others, plunging them into his body. This was perpetrated within sight of the barrack of Ruthven. [Aberdeen, 544]

The conclusion of the adventure was, that the old warrior got hold of his broadsword and put the ruffians to flight.

R. W. B.

Bibliography

The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland illustrated by Robert William Billings, architect, in four volumes.. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Son, 1852. Hathitrust Digital Archive version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 10 October 2018.

Last modified 17 October 2018