Left: Hic Santa Cecilia Virum Suum Docet (Here Cecilia Teaches Her Man), by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833-1898). Graphite, pasted on cardboard and linen support, 774 x 558 mm (30 1/2 x 22 inches). Signed v (twice, same handwriting): "Burne Jones."

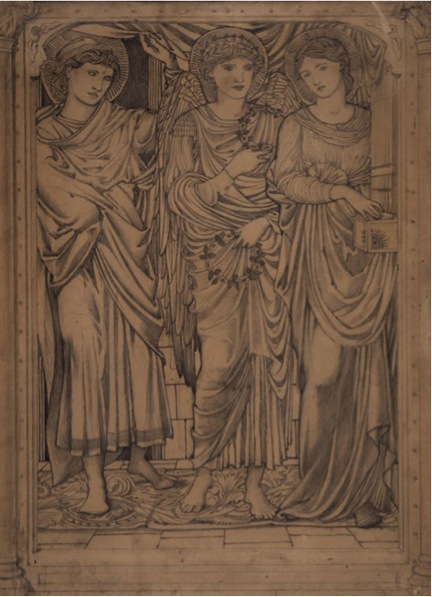

Right: Hic Angelus Domini Sanctam Ceciliam Docet (Here the Angel of the Lord Teaches St Cecilia), by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833-1898). Graphite, pasted on cardboard and linen support, 774 x 558 mm (30 1/2 x 22 inches). Signed v (twice, same handwriting): "Burne Jones." Click on image to enlarge it.

Provenance: Both works were bought as Lot 221, Stained Glass Window Designs by a "Follower of Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones," Bonhams (Oxford) 25th May 2011. Drawings were later identified by Paul Crowther as designs for the St. Cecilia windows in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The window and its individual panels are reproduced in Vol. 1 of Sewter's book (published in 1974) as plate 497.

Commentary by Paul Crowther

The signatures on the reverse of the two designs clearly match others by Burne-Jones, and are un-hyphenated. The windows were commissioned by the Christ Church Cathedral organist Dr. C. W. Corfe (1814-1883) and are situated at the east end of the north choir aisle. They were made by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. The angels in the tracery lights were designed by Morris himself, whilst the figures in the central panes and predella panes are from designs by Burne-Jones. The present works are designs for two of the three narratives from the life of St. Cecilia that form the predella.1

Various stories of the life and martyrdom of St. Cecilia emerged in the fifth century, and have long established themselves in European Christian folklore. Burne-Jones (amongst others) did a number of images of St. Cecilia, but, as far as I know, no iconographical sources for his treatments of this subject—over and above folklore—seem to have been identified by the literature. However, in his 1892 discussion of the St Cecilia windows, Malcolm Bell suggests that they illustrate a text. Bell then offers two quotations from the text, but identifies neither it, nor its author (77). However, we can now rectify this omission. The text in question is "The Second Nun's Tale" from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400). The Canterbury Tales are one of the first major works of English literature, and were probably written in the 1380's.2 It is almost certain that Burne-Jones used Chaucer for his account of St. Cecilia's life. Over and above some exact correspondences between image and text (which will emerge later) Bell must have been in personal contact with Burne-Jones, since Appendix I of his book appears to be based on knowledge of the artist's personal inventory of finished works. If, accordingly, Chaucer had not been Burne-Jones's own source for the St. Cecilia story, he would surely have corrected Bell. As it is, the book went through three editions and a reprint in Burne-Jones's lifetime, without any such correction being made.

It is also clear that Burne-Jones himself had a deep passion for Chaucer. Georgiana Burne-Jones recounts that whilst a student at Oxford, he and Morris would read Chaucer in the evenings (104). Indeed, Burne-Jones went on to illustrate many scenes from the great writer's stories, throughout his career. This starts as early as The Prioress's Tale—his first oil painting (done as a decoration for a cabinet designed by Phillip Webb in 1858). Burne-Jones's greatest tribute to Chaucer, however, is his collaboration with William Morris on the Kelmscott Press limited edition of The Canterbury Tales (published in 1896). The "Kelmscott Chaucer" is widely regarded as the most beautiful book ever printed. Chaucer wrote in Middle-English, and in works that Burne-Jones designed to accompany texts by him, the texts are in this original idiom, rather than translated into Modern English.

The Second Nun's Tale is recounted by a very spiritual woman. It centres on the legend of St. Cecilia. She came from a noble Roman Christian family, but was wedded to a noble pagan named Valirian. During the wedding ceremony, as the organ is playing, she prays secretly to God that her virgin purity will be preserved. In the bedroom, that evening, Cecilia informs Valirian that there is a great secret she wishes to tell him, as long as he will not betray it to anyone else. Valirian agrees. Cecilia then announces that there is an angel who loves her, and who is with her constantly. She must, accordingly, preserve her virginity, otherwise the angel will kill him. If, however, her virginity is respected, the angel will become visible to Valirian and will love him too. Valirian asks for proof of the angel's existence. Cecilia tells him that, in order for this to happen, he must go to the Via Appia where he will meet Pope Urban and must then be baptized. Valirian follows these instructions, and becomes a Christian. On returning home, he finds Cecilia with the angel. The angel is holding two crowns, one of which is given to Cecilia, and the other to Valirian. After various sufferings, Cecilia and Valirian are eventually martyred.

One of our two works represents Cecilia's explaining her angelic betrothal to Valirian; the other shows Valirian's (post-baptismal) return to his chamber. He pushes back the curtain, and finds Cecilia and the crown-carrying angel waiting for him. Chaucer's text for the latter scene—the first four lines of which are also quoted by Bell—is as follows. (I provide the Middle English version together with a modern English translation of each line in turn).

Valirian goth hoom and fint Cecilie [Valerian goes home and finds Cecilia] Withinne his chaumbre with an aungel stonde. [In his room standing with an angel.] This aungel had of roses and of lillie [This angel had roses and lilies] Corounes tuo, the which he bar in honde; [made as two crowns, which he carried in his hands.] And first to Cecilie, as I understonde, [The first, to Cecilia, as I understand it] He yaf that oon, and after can he take [he gave one; and then] That other to Valirian, hir make. [the other to Valirian, he gave] "With body clene and with unwemmed thought ["With clean body and with unblemished thought] Kepeth ay wel these corounes," quod he; [take good care of these crowns," said he] "Fro paradys to you have I hem brought, ["From paradise to you I have brought them,] Ne never moo ne schul they roten be, [nevermore shall they decay,] Ne leese here soote savour, trusteth me, [nor loose their sweet fragrance, trust me,] Ne never wight schal seen hem with his ye, [never shall anyone see them with his eye] But he be chast and hate vilonye.' [unless he is chaste, and hates villainy.] (35-36)

Traditionally, St. Cecilia is the patron saint of music, and in this post-baptism scene she holds the hand organ which is one of her most familiar "emblems." (The same emblem appears in the figure of St. Cecilia in the panes above the predella.) This connection probably derives, iconographically, from the mention of an organ playing whilst Cecilia prays to God for her chasteness.

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Crowther-Oblak Collection of Victorian Art and and the National Gallery of Slovenia and the Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway (2) and link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Bibliography

Bell, Malcolm Bell. Sir Edward Burne-Jones: A Record and Review. London: Methuen and Co., 1901. pp. 77, 81.

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Burne-Jones. Vol. 1. London: Macmillan and Co., 1909.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Poetical Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Vol. 3. Ed. Richard Morris. London: George Bell and Co., 1883.

Crowther, Paul. Awakening Beauty: The Crowther-Oblak Collection of Victorian Art. Exhibition catalogue. Ljubljana: National Gallery of Slovenia; Galway: Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, 2014. No. 9 and 10.

Sewter, A. C. The Stained Glass of William Morris and his Circle. Vol. 2. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1975. p. 146.

Notes

1. Burne-Jones's account book has the following entry for August 1874. "Oxford Ch. Church. Cecily window £90." As six designs would be needed for the whole window set, this prices them at £15 each. This rate is about average vis-à-vis Burne-Jones's charges for other large designs entered in the book.

2. Bell's quotations are from the edition of Chaucer edited by Richard Morris, which was reprinted in later Victorian times. See "The Seconde Nonne's Tale" from The Poetical Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, pp. 29-45.

Last modified 8 December 2014