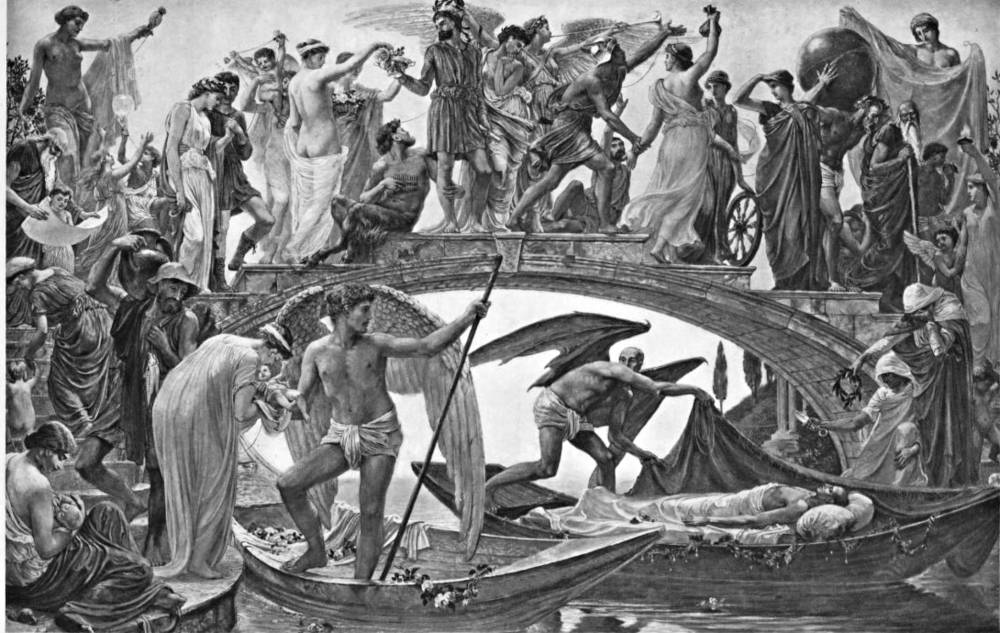

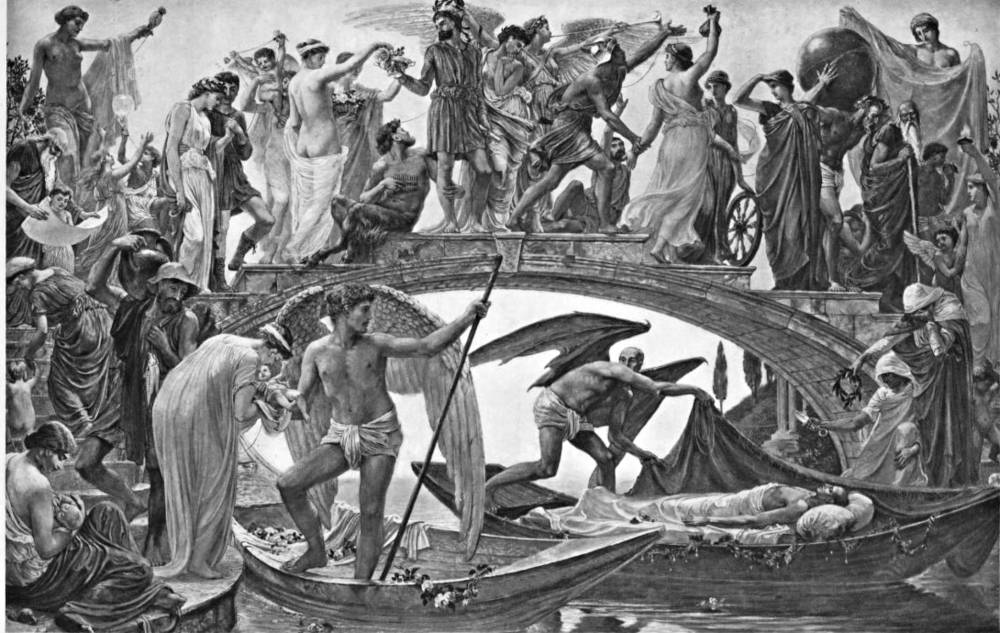

The Bridge of Life, by Walter Crane, RWS (1845-1915). 1884. Oil on canvas, 38 x 60 inches (96.5 x 152.4 cm). Private collection. Image from the Web Gallery of Art, reproduced for purposes of non-commercial academic research. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Work of Walter Crane (1898), a special issue of the Art Journal devoted to his career, included an engraving of this work, with an explanation of it by the artist himself:

The Bridge of Life, which we reproduce as an extra plate, was my picture in 1884. As far as I remember, the first suggestion came to me in Venice, in looking at the slender marble foot-bridges which cross the canals, and the mixed troops of people of all ages, sexes, and aspects, who pass up and down the steps and across them, or stop to gaze at the flickering water and the gliding, noiseless, black gondolas shooting underneath. I worked at this suggestion, and took immense pains with the design, making sketch after sketch, until I had evolved the idea in its present form.

On the frame I wrote these verses:—

that is Life? A bridge that ever

Bears a throng across a river;

There the taker, here the giver.

Life beginning and Life ending,

Life his substance ever spending,

Time to Life his little lending.

What is Life? In its beginning

From the staff see Clotho spinning

Golden threads, and worth the winning.

Life with Life, fate-woven ever,

Life the web, and Love the weaver,

Atropos at last doth sever!

What is Life to grief complaining?

Fortune, Fame, and Love disdaining,

Hope, perchance, alone remaining. [25-26]

Commentary by Dennis T. Lanigan

The Bridge of Life, one of Crane's most important and largest allegorical works, was exhibited initially at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1884, no. 206, followed by the Liverpool Autumn Exhibition in 1884, and then later at the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, Manchester, in 1887, no. 192. It was accompanied in the Grosvenor exhibition catalogue by lines from the poem Crane wrote to accompany it, which were also written on the frame. Crane felt this work "stands for the Italianised allegorical feeling of the middle period" of his career (Art Journal, 29). Crane made elaborate studies for the picture during his trip to Venice in 1883 and completed it the following year. Crane remarked: "some of the earlier studies for it, in fact, quite followed, on slighter lines, the Rialto type of bridge, but in adapting the suggestion to a purely allegorical idea much simplification became necessary" (Crane 244).

This allegory is somewhat difficult to interpret but fortunately Crane provided a detailed explanation in Henry Blackburn's Grosvenor Notes:

This design is figurative of human life in its various phases from the cradle to the grave. Life and the collective sense - life in continuity - is expressed, firstly by the marble bridge spanning the stream of time, veined and shot with various dyes and stains; viewed as a compact and independent whole, rising to its keystone, with its stairs and stages, from the water's edge, where its foundings are hidden. Next life, as in its individual sense - the course of humanity - may be traced. Here the young mother receives her first-born from the arm of the genius of life. The father with one foot raised as if about to ascend the stair, and bearing the water jar, the loaves and fishes – figuring the means for the support of life – turns to look at his child. Upon the steps a mother suckles her child, and above is teaching the infant to walk. As a boy he is taught by an old man from a scroll. Beyond rises the figure of Clotho, spinning. The Fate presiding over the beginnings of life, as living and human, but standing apart as a statue, a passionless, but half-pitying spectator. Below her a girl and a boy are playing, the boy blowing bubbles, which rise in the air and are lost. Next come a pair of lovers, or a bride and bridegroom, as she is crowned with myrtle; on the next step above, the little god Love, held aloft on the shoulder of one of the graces, showers roses upon them. A satyr, or we may call him Pan – as representing the animal impulses – holding his pipes, clings to the man in his prime, who stands above the keystone of the bridge, half turning, with a cup of glass in his hand, which the nymph of Venus fills with wine, or makes fragrant with roses. Behind him a winged genius – Fame or Ambition – holds a wreath above his head and blows a trumpet; which things indicate that in life's prime, when 'all thoughts, all passions, all delights' are in full stream, man is stimulated by ambition to win other prizes, and reluctantly turns from the pleasures of youth. At his side a woman halts and pensively gazes downward, seeing the corse on the boat passing beneath the bridge, like those, who, in life's mid-career, are crossed by the shadow of death. In front of her a man with a winged helmet eagerly presses forward, and grasping by one hand the empty hand of Fortune, stretches the other to reach the bag of gold she holds aloft illustrates the well-known dictum concerning Dame Fortune. Another aspirant has fallen in the pursuit, and vainly stretches his hand for the unattainable prize. A companion figure of Fortune turns her wheel, and lower down a woman half sadly and regretfully gazes backwards – a Lot's wife sighing for the pleasures left behind, and youth gone by – while her companion stoops beneath the weight of a globe. Thus doth man win fame, and the whole world, perchance – he exchanges the glittering bubbles and dreams of his youth for solid earth, or gold, or power, and has to bear the burden of it. A woman below him, with bowed head figures the despair of life, the shadow of success, the bane of wealth, the Nemesis of existence. An old man leaning on his staff, and on the shoulder of a youth, slowly descends the steps of the bridge – age that knows his end is near, but he is able calmly to meet it – while the careless youth holds life like an apple to his lips. Behind these a figure of Lachesis holds up a veil she has woven – the web of life, wrought with the memory of nights and days, with thought and action, with grief or delight, wherewith all life is closed. Lower down on the steps Hope holds a lamp as she looks back on the stream of humanity, while Love, frightened at the figure of Death, clings to her side. Beneath these again a child has let fall a vessel of glass – "the false and fragile glass" – which lies broken upon the marble stair. He holds by the cloak of a woman bowed in grief, who is about to place a wreath upon the bier as the boat with its dark freight passes, and Atropos, kneeling at her side with her shears snaps the thin golden thread which, from the infant in the arm of life, can be traced all through the design till it is coiled at last in the hand of Death as he draws the pall over his last victim, and his barge, along with garlands of poppies, glides on its silent way. [45-46]

Crane once again briefly explained the meaning of the painting in his reminiscences:

The legend is perhaps not difficult to read, though it is an age that loves not allegory. The thread of life from the staff of Clotho woven into its mystic and complex web by Lachesis, and severed at last by Atropos. The boats of life and of death meeting under the frail bridge. From the one, Young Life disembarking, and climbing the stairs, fostered by father and mother, led and guided and taught by Eld: following its child-like play, till made the sport of Love in the heyday of youth: till the trumpet of Ambition is heard and "the middle of life's onward way" is reached.

We look before and after,

And sigh for what is not;

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught.

Fortune and Fame pursued and ever eluding the grasp: till the crown perhaps is gained, but the burden of the intolerable world has yet to be borne. Lot's wife looks wistfully back. Tottering Eld is held by Youth; the eyes of the old man resting on the boat with its dark freight, while the boy is intent upon tasting life's apple. Hope holds her little lamp, led by Love, even on the descending steps of life; when farther down the frail glass of existence is shattered, and the mourners weep and strew the memorial flowers over the silent dead. [245]

This allegorical work was influenced by similar works by G.F. Watts and by J.M. Strudwick. Although Strudwick is not mentioned in Crane's reminiscences, the two must have been acquainted since both were friends of Edward Burne-Jones and both exhibited at venues like the Grosvenor Gallery and the New Gallery. Crane would surely have seen Strudwick's works like Passing Days exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1878, A Golden Thread exhibited at the Grosvenor in 1885, and The Ramparts of God's House shown at the New Gallery in 1889. Crane's allegorical paintings were not much appreciated in England and The Bridge of Life was eventually acquired by Ernst Seeger of Berlin, who also owned other major works by Crane. As Crane himself explained: "It seems curious that most of my principal pictures should find homes in Germany, and that hardly anyone besides Mr. Watts should have shown much interest in them. Possibly, apart from any artistic quality, the symbolic and figurative character of their subjects are more in sympathy with the Teutonic mind, and we like "all goods marked in plain figures in England" (431).

A study for The Bridge of Life sold at Christie's South Kensington, London, on 19 May 1999, lot 440.

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

This painting, considering its importance in Crane's oeuvre, was not widely reviewed. F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum felt the amount of effort expended painting this picture was not worth the reward:

In Mr. W. Crane's Bridge of Life (206) the figures are intended to illustrate the well-known allegory. Some among them are very lovely. The illumination and delicate colouring of the picture impart a charm which allegories of the didactic sort rarely possess, being in that respect less fortunate than romantic allegories. Unluckily the brilliancy and delicacy of other elements do not atone for the want of sincerity and spontaneity in the design. We have never seen a picture of Mr. Crane's which must have cost him more trouble or brought him less reward. [604]

Harry Quilter in The Spectator was almost inclined to admire the picture but, as usual, disparaged Crane's handling of the nude figure:

And of Mr. Walter Crane's Bridge of Life, we almost feel inclined to speak admirably; for he, too, tries to bring a little imagination and poetry into his painting. But his art has never embraced the possibility of drawing the nude or semi-nude figure. The absence of knowledge is invariably apparent when he attempts them, and it seems a strange fatality which causes him to continue producing pictures of which all the interest is spoilt by the bad draftsmanship of the figures. [745]

When it was shown in Liverpool in 1884, the Artist reported: "Walter Crane's Fate of Persephone , and The Bridge of Life, and Miss Pickering's [Evelyn De Morgan's] Waters of Babylon , maintain the character of the Grosvenor for quaintness, and the style of the early Italian masters" (302).

[You may use the image of the engraving without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and the Getty Art Institute and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.— George P. Landow]

Bibliography

Blackburn, Henry. Grosvenor Notes. London: Chatto and Windus (May 1884): no. 206, 45.

The Bridge of Life." The Web Gallery of Art. Web. 25 November 2025.

Crane, Walter. An Artist's Reminiscences London: Methuen, 1907, 244-45 & 431.

Important 19th Century Pictures and Continental Watercolours. London: Christie's (30 March 1990): lot 512.

Konody, Paul G. The Art of Walter Crane. London: George Bell & Sons, 1902. 89 & 96.

"Liverpool Autumn Exhibition." The Artist V (1 October 1884): 302-03.

"London Spring Exhibitions. The Grosvenor and the Water-Colour Societies." The Art Journal XLVI (1884): 190.

O'Neill Morna. Walter Crane. The Arts and Crafts, Painting, and Politics, 1875-1890. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010, 93-95 & 97-104.

Quilter, Harry. "Art. The Grosvenor Gallery." The Spectator LVII (7 June 1884): 744-45.

Spencer, Isobel. Walter Crane. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1975. 127 & 183-84.

Stevens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. The Grosvenor Gallery." The Athenaeum No. 2950 (10 May 1884): 603-04.

The El-Helou Collection. London: Christie's South Kensington (May 19, 1999): lot 440.

The Work of Walter Crane with Notes by the Artist. The Easter Art Annual for 1898: Extra Number of the Art Journal. London: J. S. Virtue, 1898: 29.

Created 4 January 2018

Last modified (commentary added) 25 November 2025