Heinrich Wölfflin’s The Principles of Art History (1915), a pioneering work that sought to explain the fundamental formal differences between Renaissance and Baroque painting, sculpture, and architecture, offers insights into the ways the early and late pre-Raphaelites handled line and depth. His book’s subtitle, “The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art,” nicely captures the situation(s) in which the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood found themselves and the ways in which they developed in their “later art.”

According to Wölfflin, European painting divides into two fundamentally opposed ways of depicting the visual world, neither of them superior to the other. These he calls somewhat confusingly the linear and the painterly — confusingly because they both are forms of painting and other visual arts. According to Wölfflin,

The great contrast between linear and painterly style corresponds to radically different interests in the world. In the former case, it is the solid figure, in the latter, the changing appearance; in the former, the enduring form, measurable, finite; in the latter, the movement, the form in function; in the former, the thing in itself; in the latter, the thing in its relations. And if we can say that in the linear style the hand has felt out the corporeal world essentially according to its plastic content, the eye in the painterly stage has become sensitive to the most various textures, and it is no contradiction if even here the visual sense seems nourished by the tactile sense — that other tactile sense which relishes the kind of surface, the different skin of things. [27]

Since the painterly style, which we find in, say, Raphael, Tintoretto, Turner, and Watts, had the most prestige during the Victorian period and when Wölfflin wrote, he emphasizes that

The painterly is not a higher stage in the solution of the one problem of the imitation of nature, but a totally different solution. Only where decorative feeling has changed can we expect a transformation of the mode of representation. Not with the cool decision to perceive things from another side for once, in the interests of verisimilitude or completeness, do painters strive to seize the picturesque beauty of the world, but struck by the charm of the of picturesque. It is no progress due to a more consistently naturalistic attitude if painters learned to separate the fragile painterly semblance-picture from tangible visible things. That is determined by a new sense of beauty, by the feeling for the beauty of that all-pervading mysterious movement which, for the new generation, at the same time meant life. All the processes of the painterly style are only means to an end. Even unified vision is not an achievement of independent value, but is a process which arose with the ideal and declined again with it. [28]

The history of art, in other words, is not a history of progress but a history of changing ways of wanting to see and depict the world. When the young men who formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood rejected the teachings of the Royal Academy which promulgated what Wölfflin termed painterly style, they chose to follow the artists of the Northern Renaissance and Early Italian Renaissance and emphasize the flat plane and sharp, distinct edges — something that characterizes Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents and Lorenzo and Isabella, Hunt’s Missionaries, and Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin.

Left: John Everett Millais. Christ in the House of His Parents. 1849-50. Oil on canvas, 34 x 55 inches; 864 x 1397 mm. Tate Britain. Right: Claudio and Isabella.

Left: The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). 1848-49. Tate Britain. Right: William Holman Hunt. A Converted British Family sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids . Ashmolean Museum.

This emphasis upon line is what Ironside refers to in his pioneering 1948 book on the Pre-Raphaelites when he points out that

considering the sources of the Pre-Raphaelite style, if, in seeking to assign to its brief, intense life the right place in the travelled sequence of human inspiration, we can, without duly straining the issue, pointe to related traits in the style of Ingres and his followers, then we need not feel deterred by logic from extending the the comparison to Davis himself (10).

These works aggressively rejected the then orthodox rules of composition and lighting that dominated British painting: pictures should have one major source of light supplemented by a minor one from the opposite direction, and the emphasis should be on color rather than line. (Hunt offers Wilkie’s Blind Fidler as an example of what audience and academicians alike thought proper). Instead they follow what Wölfflin calls the “phenomenon of linear style [in which] line signifies only part of the matter, and [in which] the outline cannot be detached from the form it encloses. We can . . . say for once as a beginning—linear style sees in lines, painterly in masses. Linear vision, therefore, means that the sense and beauty of things is first sought in the outline” (18).

Two by Millais from the early and later parts of his career: Left: Mariana 1850-51. Oil paint on mahogany. Tate Britain. Right: Apple Blossoms or Spring. 1858-59. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

Malcolm Warner, whose extensive catalogue entry in the 1984 Tate exhibition catalogue, describes the many changes the painting took before its final form as it evolved from a medieval scene to modern picnic, adding that “in the frieze-like arrangements of figures against an orchard background, the work also recalls Botticelli’s same treatment of the same theme in the famous Primavera” (171). But the Pre-Raphaelites, even in earliest days when they were most programmatic, also painted works with receding backgrounds, such as Millais’s The Woodsman’s Daughter (1850-51), Brown’s The Pretty Baa Lambs (1851-59), Hunt’s Hireling Shepherd (1851-52), Brett’s Stonebreaker (1857-58), and of course Millais’s The Blind Girl (1854-56).

Left: The Woodsman's Daughter. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96), 1850-51. Oil on canvas, 35 x 25 ½ inches. Guildhall Art Gallery, Corporation of London Middle: . Middle: The Hireling Shepherd. William Holman Hunt. 1851. Oil on canvas, 30 1/16 x 43 ⅛ inches. Manchester City Art Galleries. Right: The Blind Girl. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1856. Oil on canvas, 32 x 24 ½ inches Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery [Click on images to enlarge them.]

As Millais’s beautiful Mariana makes very clear, the young painter moved quickly towards Wölfflin’s painterly style, though the sharp edges of the woman’s face and stained glass show him trying to find a way to blend both approaches to color, drawing, and space. In fact, if one follows Millais’s career one observes him occasionally returning to painting pictures in which figures appear sharply outlined against a distant background, something we see in Apple Blossoms (or Spring). In works like these he seems an entire different painter than the one who produced Mercy: St Bartholomew’s Day, 1572 and The Black Brunswicker. Many of Millais’s portraits, like those of Watts, remove the problem of background and depth by depicting the sitter against a dark or even black background, allowing the artist to concentrate in the painterly: something we see in works that range from his early portraits of Emily Patmore (1851), Annie Miller (1854), and John Wycliffe Taylor (1864) , to his 1884-85 portrait of Gladstone and his 1883 self portrait (Millais Portraits nos. 29, 10, 34, 40, 45). Of course, the versatile Millais also occasionally placed his sitters in rich and complex backgrounds as he does in his famous portrait of Ruskin, that of the Wyatt family, and Leisure Hours (nos. 23, 4, 330, but most of his sitters appear against dark, plain background.

Three by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Left: Paolo and Francesca. 1849-62. Mixed media, 12 ½ x 23 ¾ in. Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford. Middle: The Beloved. 1863. Oil on canvas Right: Beata Beatrix. 1864-70. Oil on canvas, 32 x 26 inches. Tate Britain.

Rossetti, that charismatic painter of extremes, at least as far as his compositions goes, creates flat compositions, such as Dantis Amor 1859-60), originally painted for a piece of furniture, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855) and The Beloved (or The Bride, 1865-66), whose composition Tim Barringrer described “as opulent to the point of claustrophobia”. On the other hand, we have the purely painterly Beata Beatrix (c. 1864-70), whose style, Barringer points out, “differs greatly from the sequence of Venetian-inspired opulent beauties inaugurated by Bocca Bacciata. Ethereal and dimly lit, its dreamlike atmospherics and visionary intensity indicate the unique status of this workin Rossetti’s canon (2012: 166-67). More commonly from very early works like Dante Drawing Beatrice to Lady Lilith (1866-8; altered 1872-73, he used the depth-creating techniques the Pre-Raphaelites learned from Early Netherlandish painting — an open window (or, as here, mirror reflecting a window) that appears in Henry Wallis’s Chatterton (1855-56), Hunt’s Awakening Conscience, Claudio and Isabella (1850-53), and Millais’s Isabella (1848-49) and Mariana (1850-51)

Left: Lady Lilith. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Oil on canvas, 38 x 33 ½ inches. Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware. Middle: The Awakening Conscience. 1853. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 55.9 cm. Tate Britain Accession number T0.2075. Presented by Sir Colin and Lady Anderson through the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1976. Right: Chatterton. Henry Wallis. 1856. Oil on canvas, 24 ½ x 36 ¾ inches. Tate Britain.

My main point here is that all the members and associates of the Pre-Raphaelites throughout their careers move between what Wölfflin termed the linear and the painterly, sometimes emphasizing the first, other times the second, and often making attempts, not always successful to combine the two. One way to put this is that the linear mode of perception and drawing never entirely left their way of seeing the world; or one could say that the ghost of the early PRB occasionally — only occasionally — haunts the later work. Burne-Jones combines these two fundamentally opposed approaches to presenting the visual world by placing the main subject in a plane and then using chiarscuro in the depth, as we see in works like The Love Song. Funded by Ruskin, he travelled to Italy and fell in love with the later Italian masters, but upon his return and throughout his entire career he tends to use them in a subsidiary form.

Left: The Beguiling of Merlin. 1874. Oil on canvas, 73 x 43 3/4 inches. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight. Right:Laus Veneris (In Praise of Venus). 1873-75. Oil on canvas, 47 x 71 inches. The Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

In works like The Beguiling of Merlin theme and technique coincide as the emphasis upon the plane merges with the subject of the painting — theme and style merge — as the stalwart of Arthur’s kingdom is trapped in this claustrophobic flattened world. Laus Veneris (In Praise of Venus) is another work the emphasis upon the plane perfectly aligns with the painting’s mood and theme: Venus and her attendants exist in one flat plane while the knights appear in a second one outside a tiny window. More commonly Burne-Jones presents the painting’s major interest in a flat plane and then creates a shadowy painterly distance the way he does in The Mirror of Venus and Love and the Pilgrim.

The Mirror of Venus. Oil on canvas, 47 1/2 x 78 3/4 inches. Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon.

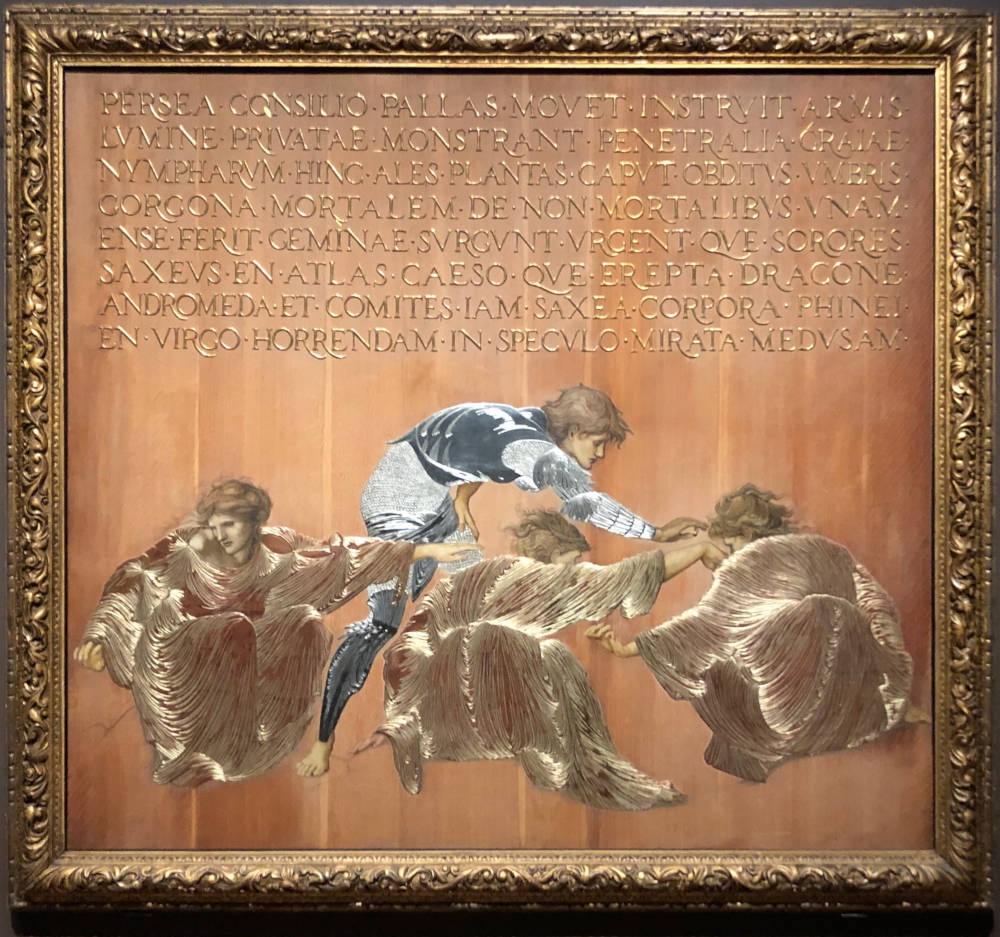

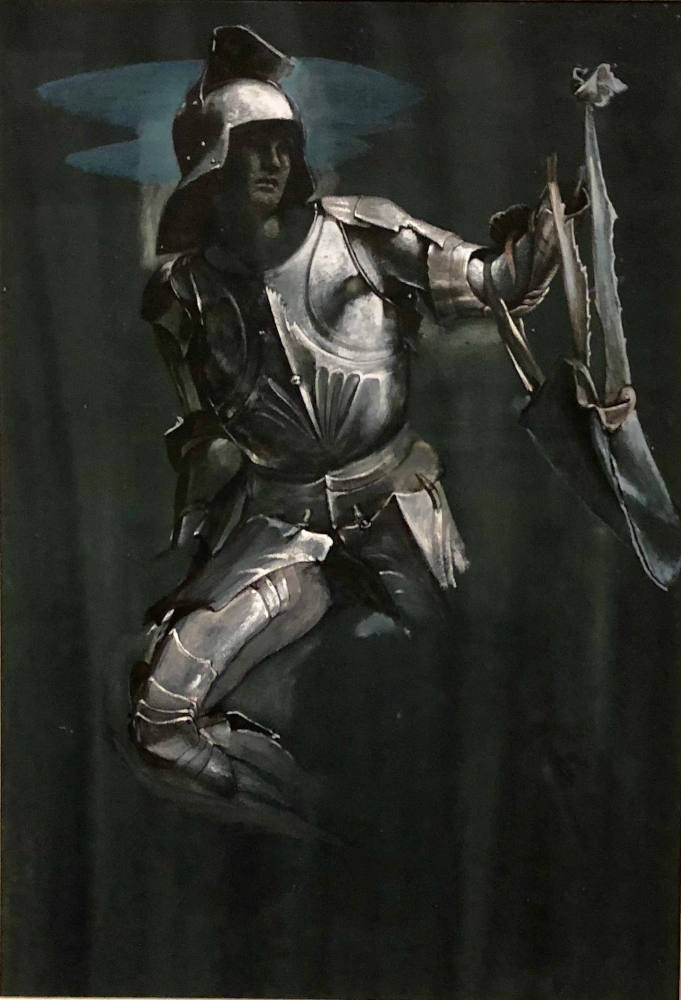

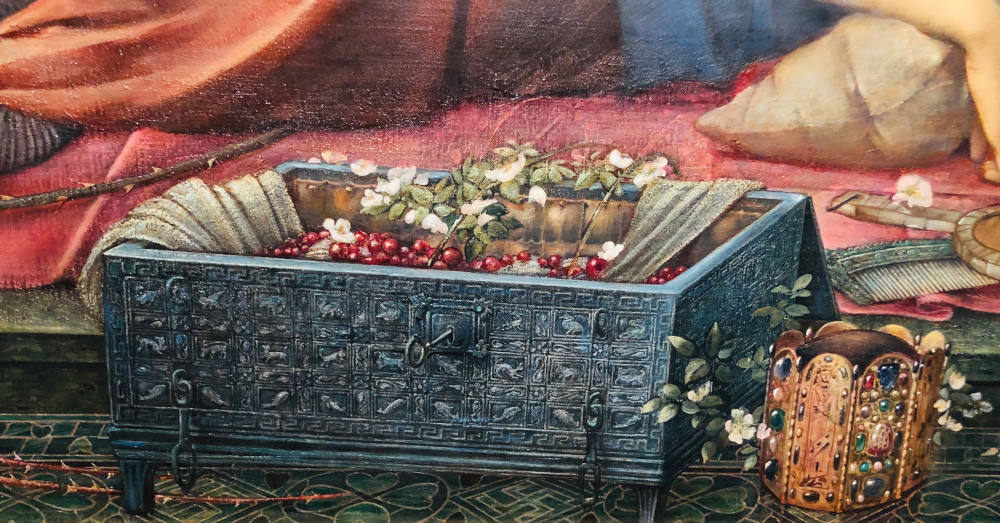

As the wonderful Burne-Jones exhibition at Tate Britain makes starkly clear, to the end of his career he remained an artist pulled in the opposite modes of the linear and what Wölfflin calls the painterly. His version of Perseus and the Graiae in which the figures appear upon a plain wooden panel, like his casket of jewels in the Briarose series, shows his linearity while his study of a shadowy knight in armor reminds us of his painterly side.

Left: Perseus and the Graiae. Middle: The Shadowy Knight. Right: Jewel Casket.

Bibliography

Barringer, Tim, Jason Rosenfeld and Alison Smith, with Contributions by Elizabeth Prettejohn and Diane Waggoner. Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing, 2012.

Ironside, Robin, and John Were. Pre-Raphaelite Painters. London: The Phaidon Press, 1948.

Wölfflin, Heinrich. The Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art. (1915). Trans. M. D. Hottinger. 7th ed. New York: Dover Publications.

last modified 15 April 2022