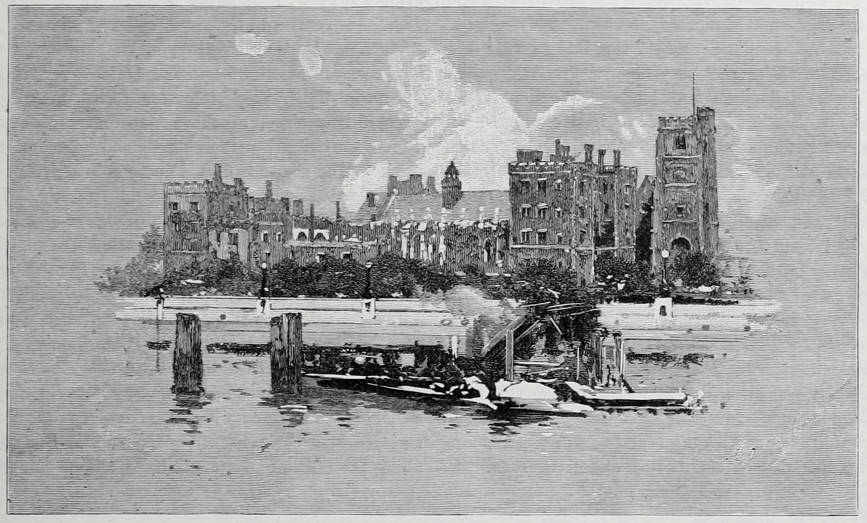

Lambeth Palace. George Seymour. c. 1882-83. Source: Watson, “The Lower Thames —I,” 489. [Click on image to enlarge it.]Image capture and formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and the University of Toronto and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

At Vauxhall Bridge we come in sight of Lambeth — first of Doulton's elaborate factory, to which the word “handsome” seems most applicaljle, then of Lambeth Palace, of St. Thomas's Hospital, and finally of Westminster Bridge. With Lambeth Palace our artist has dealt very lovingly, vignetting it so as to leave out Lambeth Bridge, and bring into the foreground the old, curious, ramshackle landing-stage, which is so placed that it might have been designed expressly to break the stony severity of the Embankment. To all Englishmen who esteem the history of their country Lambeth Palace is of scarcely less interest than the Tower. It has been the scene of councils and convocations. Here Sir Thomas More was summoned before Cranmer, and Cranmer before Cardinal Pole. Here, too, Anne Boleyn did penance in the brief interval between her condemnation and her death. It is as if on every stone of Lambeth Palace the record of some troubled period of our history were graven. But into matters of history I need not enter here. In point of pieturesqueness Lambeth Palace is unique, being not only curious and varied in its forms, but also very opulent in beauty and variety of colour. Probably pilgrimages to it would be more frequent if it had not so powerful a rival on the other side of the water. Of the architectural qualities of the new Palace of Westminster, which Mr. Seymour has also drawn for us, there will always be diiferenees of opinion more or less bitter. The palace of the archbishops is the accident of many centuries; the Houses of Parliament have all the advantages that may be supposed to belong to unity of design. They are best seen as in our picture. Thus viewed, the building appears less scattered than from any other point of view — less dwarfed in height by its tremendous length. It is ennobled, too, by its contrast with the most squalid, and yet most really picturesque, portion of Westminster. The shore between Lambeth Bridge and the Embankment, which is shown in our last two illustrations, is admirably typical of most of the scenery of the Lower Thames. Half-ruined warehouses, crumbling wharves, coalbarges, sheds, decaying timbers, and a general aspect of going to the bad — these elements, unsightly enough to those who love only regularity of line and imposing stone or stucco fronts, are rich material for the harvest of a quiet eye; and there are few places at which the elements of a good picture lie more ready to the hand than on that part of banks of Thames which fronts the quaint stateliness of the archiepiscopal Palace at Lambeth. [491-92]

Other images of Lambeth Palace

- Lambeth Palace — Water Cresses — drawing by John Leighton

- Paddlewheel Thames Ferry near Lambeth Palace — engraving from The Book of the Thames

- Lambeth palace. Surry [sic]. — from Eighty Picturesque Views of the Thames and Medway

- Lambeth Palace — etching by T.R. Way

Bibliography

Watson, Aaron. “The Lower Thames —I.” The Magazine of Art. 6 (1882-83): 485-92. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 15 November 2014

Created 14 November 2014

Last modified 20 March 2022