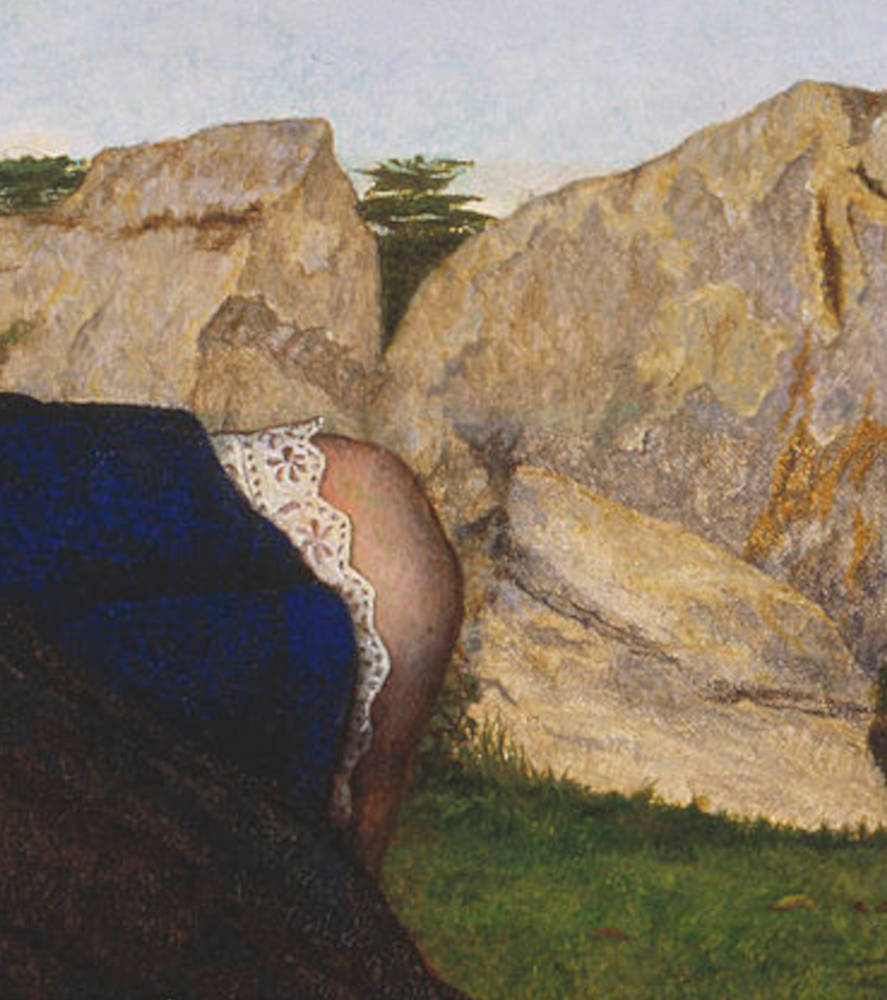

Robins of Modern Times, c.1860. Oil on canvas, 19 x 33 &fra342; inches (48.3 x 85.7 cm). Private collection.

his is one of Stanhope’s most atypical and enigmatic paintings. Even the exact meaning of the title remains a mystery. It was obviously influenced by the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism with its brilliant colour and meticulous detail. In emulation of early Netherlandish Renaissance artists it was painted with the use of thin transparent or translucent paint on a white ground. This painting fully justifies Edward Burne-Jones’s claims about Stanhope that “his colour was beyond any the finest in Europe… An extraordinary turn for landscape he had too – quite individual” (Lago, Burne-Jones Talking, 76-78).

Simon Poë, the leading Stanhope scholar, writes that this painting

shows a young girl, no longer quite a child, lying on a patch of grass on a rocky outcrop overlooking fields where men with teams of horses are ploughing. On the horizon, beyond the trees, we can glimpse a half-timbered farmhouse. The girl is lying with one knee raised so that her skirt has fallen back. Her dress is dark blue, and she is wrapped – entangled might almost be a better word – in a black cape or cloak. She holds a plaited crown of daisies in her right hand and clutches her side with her left. Scattered around her are broken twigs, fallen leaves and two apples. Very close, one at her foot and one at her head, stand a pair of robins. Her abundant brown hair is loose and fanned about her head. Throwing out a shoot towards her, prominent against her hair is a patch of bindweed. Her heavy-lidded eyes are half closed and her lips pursed as if for a kiss. The blush on her cheek offers a visual echo of the rosy apples and the cock-robin’s red breast. [45]

Poë has attempted to explain the meaning of this mystifying and disturbing painting by linking it to Stanhope earlier Thoughts of the Past. The two paintings are painted on canvases of the same size with one being horizontal in format and the other vertical. He feels “the two suggest a linked pair of momentous events that form the opening and closing of a tragic narrative. G. P. Boyce’s diary for June 21, 1858 reported: “Went into Stanhope’s studio to see the picture he is engaged on of an ‘unfortunate’ in two different crises of her life” (25). Many scholars feel that of the two paintings mentioned only Thoughts of the Past was ever completed. Poë, however, feels it is possible that Robins of Modern Times is, in fact, the second of the two crises mentioned (46) and represents a young girl after she has lost her virginity. Certainly the pose of the young girl is disquieting. Are the two paintings linked by both being dressed in blue - a blue wrapper of the young woman in Thoughts of the Past and a blue dress for the girl in Robins of Modern Times.

[Click on images to enlarge them.]

Like Stanhope’s earlier Thoughts of the Past this second painting is full of symbolism. The apples shown are frequently symbolic of the temptation and the fall in the Garden of Eden. The girl is shown in an unploughed patch of wild nature, possibly representative of Eden. She has brought two apples, perhaps one intended to be given to her sweetheart that she has arranged to meet. Could the bindweed imply she is somehow ensnared and are the broken twigs and fallen leaves somehow symbolic of her loss of virginity. The girl has removed the daisy chain crown from her head, possibly suggesting she has also “put off childhood and innocence along with it” (47). While we might feel that the girl is disquietingly young to have lost her virginity Poë points out the age of consent at that time was only twelve years old. He feels even the ploughing can be read symbolically – “the plough a male symbol, the earth female, opened and made ready for the sowing of seed” (47).

The subject in this painting appears unique and does not seem to have been inspired by any similar Pre-Raphaelite works. The closest perhaps is Arthur Hughes’s The Woodman’s Child, also of 1860, that shows a child sleeping in a forest while her parents work in the background. A robin can be seen perched on a tree trunk behind the sleeping child. The subject is straightforward and innocent in this case, however, and not at all mysterious like in Stanhope’s painting.

Bibliography

Lago, Mary Ed. Burne-Jones Talking. His conversations 1895-1898 preserved by his studio assistant Thomas Rooke. London: John Murray, 1982.

Poë, Simon. “Robins of modern times. A modern girl in a Pre-Raphaelite landscape.” The British Art Journal 4 (Summer 2003): 45-48.

Surtees, Virginia Ed. The Diaries of George Price Boyce. Norwich: Real World, 1980

Last modified 7 May 2022