The illustrations in this review come either from our own website or from the exhibition image sheet and press release kindly provided by Leighton House Museum. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.] — Jacqueline Banerjee

The Exhibition

The current Leighton House Museum exhibition, "Alma-Tadema: at Home in Antiquity," has been brought over from the Fries Museum in Leeuwarden, Friesland, where the future Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema lived as a boy. It has been co-curated at this end by Elizabeth Prettejohn and Peter Trippi, together with Leighton House Museum's own senior curator, Daniel Robbins. Collectively these experts have achieved a wonderful exhibition that unveils much about an artist we perhaps constrain by our own ignorance.

Although the exhibition is a collaborative effort, it pulls especially on Prettejohn's article of 2002, "Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Modern City of Ancient Rome," in which she argues that Alma-Tadema's representations of the ancient city of Rome can be seen as significant explorations of urban experience, parallel to the more familiar nineteenth-century representations of modern Paris. The late nineteenth-century notion of the city's modernity thus provides a novel perspective on the traditional fascination with Rome as the ultimate paradigm for the urban.

The exhibition's stated objective is to explore Alma-Tadema's "fascination with the representation of domestic life in antiquity and how this interest related to his own domestic circumstances expressed through the two remarkable studio-houses that he created in St John's Wood together with his wife Laura and daughters" — and also to show how his work "fixed ideas in the popular imagination of what life in the ancient past 'looked like'" ("Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity"). It helps that this delightful exhibition displays the paintings within the familiar house of another giant of the Victorian art world. The calculated use of the domestic space forces us re-engage with works that convey a certain air of Victorian domesticity, even though their setting is generally that of the distant past of another country. We are encouraged to look with new eyes at this artist we thought we knew.

The Artist

Self-Portrait, 1852, from the Fries Museum. Collection: Royal Frisian Society.

Alma-Tadema was born Lourens Alma Tadema* in 1836 in Northern Holland. Moving to Belgium in 1852 when he was sixteen, he commenced a four-year training period at the Royal Academy of Antwerp, where he produced strong images like the self-portrait shown on the left, now on display in the drawing room of Leighton House. This first room surprises us with its dark paintings, although it should not when we consider Alma-Tadema's geographical and artistic background. It also shows us how important the various members of his family were to him. Here we get a chance to meet them, for instance in the deftly executed pencil drawing Portrait of Lourens Alma Tadema, his Brother Jelte, his Mother and Sister Artje (1859, also from the Fries Museum). There are moments of excellence in this introductory room although those who have an appetite for the Romanesque works may not enjoy the dark muddy tones of some of these earlier paintings. In any case, note the expression and headdress of Queen Fredegona in Queen Fredegona at the Death-Bed of Bishop Praetextatus (1864, another painting from the Fries Museum); note too the bright silk of the central figure in The Visit: a Dutch Interior (1968), brought in from our own V&A.

In 1863 Alma-Tadema married Marie-Pauline Gressin Dumouli, known as Pauline. They honeymooned in Italy and saw Rome and Florence, and these influences drew him away from the darkness of his 1850s works. We, like the figures in Leaving Church in the Fifteenth Century (1864), move away from the darkness into Italian blue skies and peach-gold sunshine. We meet Pauline in Pompeii (1863), a work which indicates the strange pairing of Victorian domesticity and the Romanesque. So often the faces of Alma-Tadema's women look Victorian — as in Lesbia Weeping over a Sparrow (1866), and Flowers (1868).

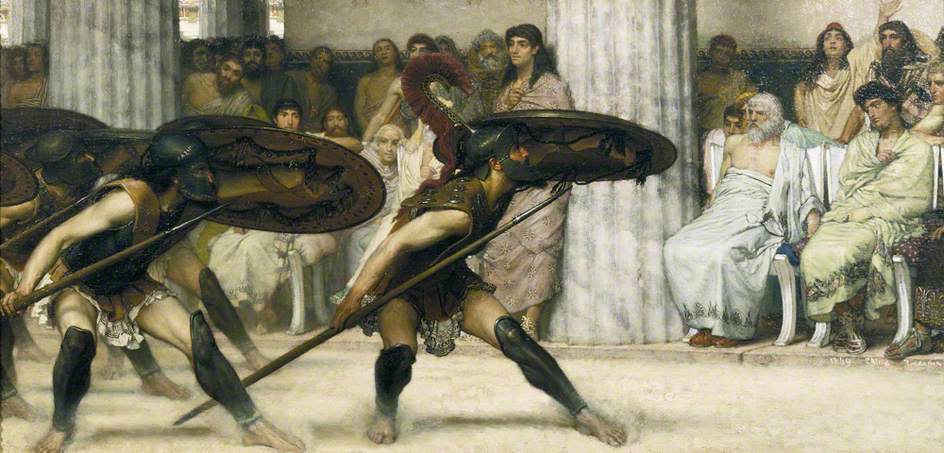

A Pyrrhic Dance, 1869, from the Guildhall Gallery, displayed here in the dining room among his works from the 1860-70s.

This second room offers early but decidedly lighter classical images such as the powerful cinematic work A Pyrrhic Dance (1869), the exquisite A Greek Woman (1869) and the lively conversation of The Wine Shop (1869). The energy of these works is decidedly pagan, not Protestant. "The gesticulations of the 'barman' to his toga-clad customers in The Wine Shop could have come straight from some East End boozer," writes Mark Hudson, and indeed, it could.

This artistic move from dark to light seems also, in part at least, to have been influenced by changes in Alma-Tadema's own life. His first wife Pauline died in 1869 at the age of just thirty-two, soon after their young son died of smallpox. He was left with two daughters, Laurense and Anna, to care for. After these losses and the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, Alma-Tadema moved to London where he stayed for the rest of his life.

Whilst in England he befriended members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle and when attending a party at the home of Ford Madox Brown, Alma-Tadema met the young Laura Epps. She was seventeen; he was twice her age. They were married by July 1871 and seem to have been well-suited: although this marriage produced no children, it bore fruit in another way. As Hudson says, "Under his tutelage, she became a painter herself, and the pair set about what the exhibition describes as 'time-travelling' through their art." Many of Laura's works are displayed here too, including her fine portrait of her husband, one of a pair that they painted of each other in 1871 to commemorate their wedding, and which are displayed in Leighton's bedroom.

The Alma-Tademas

Two paintings on display in Leighton's studio. Left: Sweet Industry, 1904, by Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema. © Manchester Art Gallery. Right: Bath of Cupid, by Frederic Leighton himself, © Ann and Gordon Getty — it was painted for the Alma-Tademas' Hall of Panels (see below).

In her time, Laura was successful in her own career although her name has now been supplanted by her husband's. This exhibition does much to correct that imbalance and Laura's A Birthday (1884), Bright be Thy Noon (1894) and Love's Beginning (1904) are all worthy of note. The same is also true of her step-daughter Anna Alma-Tadema's works, for example her wonderful Self-Portrait (after 1886), on display in the studio.

Townshend House, the family home, was an important centre of creativity: Laura and Anna's works tell us much about the domestic space, while Alma-Tadema transformed it. A series of small narrow works called The Hall of Panels was created by the Alma-Tademas and their friends for their next house in Grove End Road, and demonstrates their artistic and sociable natures. Seventeen of the original forty-five panels have been assembled for this exhibition and provide an extraordinary insight into their circle, including as they do works by Frederic Leighton, as well as John Singer Sargent, Val Prinsep, Frank Dicksee and Henry Moore (who were also regular visitors to Leighton's home).

The Paintings

Unconscious Rivals, 1893, © Bristol Museums & Art Gallery, displayed here in the Upper Perrin Gallery among Alma-Tadema's late works.

Alma-Tadema's paintings have a certain quietude to them, as we can see in Unconscious Rivals (1893), which is pregnant with silence, despite the potentially loud clash suggested by the title. The painting's orange light falls on two Patrician women lounging in a villa whilst perhaps awaiting the return of a (shared?) male lover. The expressions of the women are hard to decipher, although the reason for their rivalry is hinted at by the sculpted gladiator foot which breaks through from the right-hand edge of the frame. The full sculpture remains out of sight, like the true reason for their rivalry. Prettejohn argues that this particular painting's legibility is fragmented, with the fragment of the large sculpture making it more so — as Joanna Paul suggests (116). Such fragmentation and consequent lack of comprehensibility is part of what makes Alma-Tadema's works easy to skip past, but it is also part of what brings the viewer back to them. There is something intriguing and inviting, something within the paintings which is unsaid and cannot ever be resolved.

Alma-Tadema's A Hearty Welcome (1878) shares this unsaid quality but also evokes the domesticity already mentioned. In this wonderful frieze-like painting, the whole family are present. They appear as Ancient Romans, but are decidedly Victorian. These are modern people playing with/in the past. But Alma-Tadema's subject is not archaeological nor is it psychological, instead it is the light which he explores. He watches it light up the bright yellow sunflowers in the background and move round to the orange painted pillars. These pillars are extensions of the bright red poppies which strain upward toward the light in which the sunflowers are basking. There is a silence in this work though, and instead of being a frieze, it becomes a "freeze": a kind of cinematic still.

Perhaps the domesticity in his works speaks for itself: after all, does he not simply show us everyday interactions between people? This reading is certainly in keeping with Prettejohn's thesis that his work was a (then) contemporary exploration of past urban experience. In some ways the periods are interchangeable, the figures engaged in their daily activities merely made different by virtue of costume. The exhibition, crammed full as it is, allows one to move between the classical world, which was brought to life during Alma-Tadema's own time by the excavation of Pompeii, and the Victorian, gently negotiating between the two as he did himself.

I suggest that it is in the smaller, more intimate pieces, with their patient rendering of minute detail, that Alma-Tadema really shines. But later on in the exhibition, there are theatrical designs that lend themselves particularly well to Prettejohn's thesis about the metropolitan aspect of his work. For example, Entrance to a Roman Theatre (1866) displays the social life of a town where the inhabitants know each other. Prettejohn describes "the chance encounter" of the two pairs who exchange greetings, although she notes they are not social equals (115). We witness the marked difference between the patrician family and the parvenu family who are trying too hard to show their status. The figures in this scene are identifiable, unlike those in his later works, where the figures dissolve into blobs of paint. It was in the 1870s that Alma-Tadema more fully turned to what Prettejohn describes as "the metropolitan environment of Rome" for inspiration, and produced works of the quality of Audience at Agrippa's (115-16). This is an urban work which along with its paired After the Audience of Agrippa explores the urban blurring of faces of people thronging an imperial metropolis.

Audience at Agrippa's was well received in its time, and Alma-Tadema's reputation was based on the success of such works, to the point where he was invited to contribute a Self Portrait (1896) to the Vasari Corridor. However, after his death in 1912, he gradually fell out of favour like so many Victorian artists. An indication of his current return to favour is his influence on cinema: Arthur Max, Ridley Scott's production designer, has stated that the team worked with a sheaf of reproductions of Alma-Tadema paintings when filming Gladiator (2000). The exhibition has two large television screens which run images of the paintings alongside various film clips, including those from Gladiator. The film will no doubt by watched with fresh eyes by many visitors.

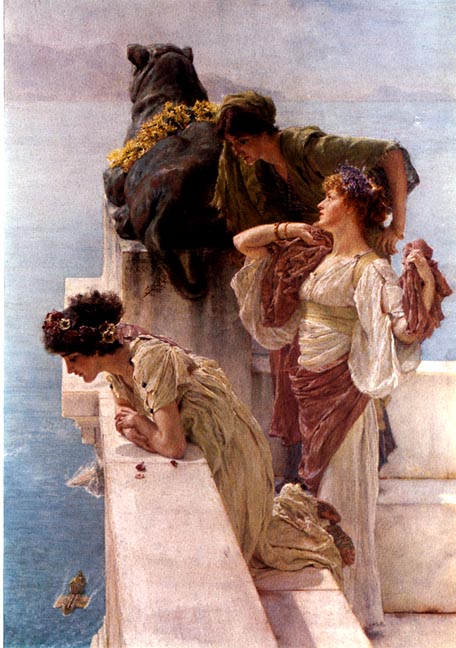

Two paintings among the late works on display in the Upper Perrin Gallery: A Kiss (1891), now in the private collection of Martin Beisly. Right: A Coign of Vantage (1895).

Those seeking the more picturesque images typically associated with Alma-Tadema will respond to his tender painting, A Kiss (1891), linger over Water Pets (1874), and dive into the beautiful colours of A Coign of Vantage (1895). In the last-mentioned work, despite its bright Mediterranean vista, we find women who look Victorian, waiting as if they are at the Moulin Rouge, and about to welcome the performers to the stage (in this case the sailors returning home). The colours and textures of all these delightful works allow us to dream about and disappear into a self-indulgent place where time is fragmented, and meaning is undefined, where people are unconstrained by time and place.

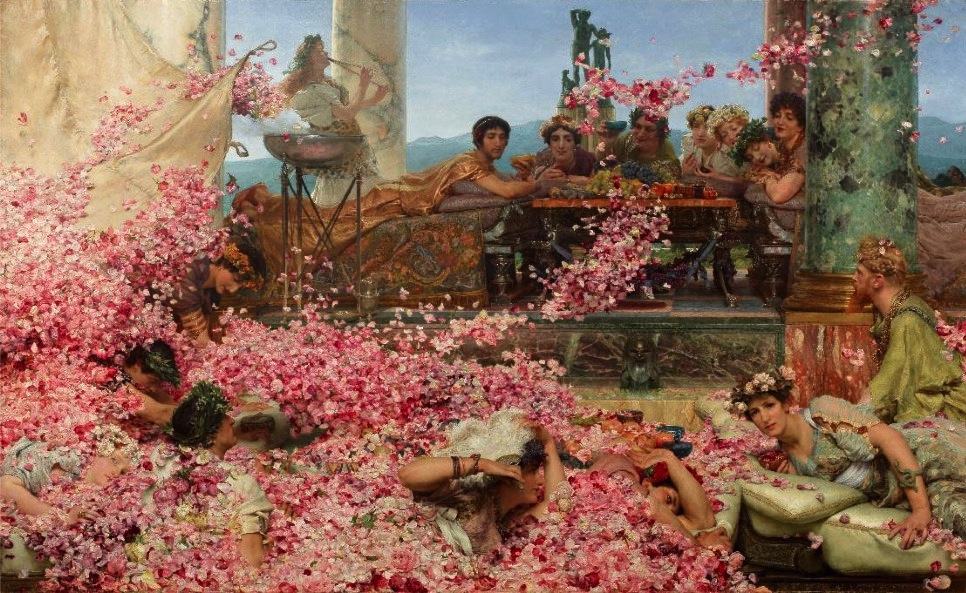

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), from the Pérez Simón Collection.

Turning to Alma-Tadema's The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), which was previously on display at Leighton House in 2015, we find Heliogabalus (the Emperor Elagabalus) and his preferred guests sitting as if they are at a symposium, looking down upon an abundance of rose petals. But as we turn to the left-hand side of the painting we start to see something else besides the beauty of the roses, the wonderfully pink petals which fly through the scene and fall in heavy mountains: Heliogabalus is burying the rest of his guests under them. He is suffocating them, slowly and beautifully. On the far left, a figure with a pair of blue eyes is buried beneath the roses, and although he peers out at us with a cold bright stare, he is being engulfed by the petals. Nearby a dark-haired figure lies, almost in repose, but is weighted down by a blanket of unrelenting roses. The sheer decadence of this work, beautiful as it is, is revealed by the imminence of death, and the cold undertone of the emperor's imperial indifference. Like him, we seem to to watch events on loop, and see people being entombed slowly, over and over again. The painting is a confusing mix of visual delight and dis-ease. However, it has come to be seen as Alma-Tadema's magnum opus — at least until it was displayed alongside The Finding of Moses in this exhibition.

The magnificent The Finding of Moses (1904), from a private collection.

For many, The Finding of Moses (1904) will be the highlight. It was cut out and rolled up when a gallery could only find a buyer for its frame, but when it went on sale in 2010 it sold for the unexpected and record price of £27 million. It still holds the record for a Victorian masterpiece sale, but since it is held in a private collection, it has not been displayed in Britain for over a century. I would urge you to take the opportunity to see it whilst you can. Prettejohn has intimated that the identity of the owners is unknown even to the curators themselves, but that they were very happy to be able to display it here. It is a monumental piece and I am also delighted by its inclusion.

There is another rare opportunity here too, to see Alma-Tadema's Portrait of Leopold Löwenstam (1883), which is also in a private collection. Löwenstam was his engraver, and the portrait was rediscovered in 2016 during the Antiques Roadshow where Rupert Maas identified it. The portrait, which has never been publicly exhibited, shows Löwenstam creating an Alma-Tadema engraving: the production of such engravings was a vast source of income for artists during the nineteenth century. 1883 was a hugely successful year for Tadema who became an A.R.A that year and moved into a bigger house, no doubt funded partly by the print trade.

Conclusion

Despite the Roses of Heliogabalus being referred to as a "frankly ludicrous canvas" by Rachel Campbell-Johnson, I suspect we are now beginning to learn how to respond to Alma-Tadema's pastel canvases. We have learned, with the help of the Pérez Simón Collection, to allow our senses to be enraptured by Alma-Tadema. We have learned to allow our mind to wander as our eyes drink in the sunlight, and the infinite detail which fills every inch of the canvas. What Prettejohn and the others within this curatorial success are now asking us to do, is to consider what more we may understand about the Victorian metropolis and the Victorians' feelings about urbanisation and cosmopolitanism.

This exhibition runs until 29 October and provides a unique opportunity for visitors to absorb the many details and ponder the many silences within the works — and also to revisit some popular films in their minds. There is time yet for work to be done on Alma-Tadema, and Trippi, Prettejohn, Robbins and their team have paved the way for new conversations about modern masters who used ancient languages.

*Although the artist himself did not use a hyphen in his name, the modern convention is to employ one. This website has followed the lead of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in this respect.

Bibliography

"Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity" (Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea site). Web. 29 August 2017.

Campbell-Johnson, Rachel. "Not 'the worst painter of the Nineteenth Century' after all." The Times. Web. 29 August 2017.

Hudson, Mark. "An evocative reappraisal of a Victorian great — Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity, Leighton House Museum, review." The Telegraph. Web. 29 August 2017.

Kennedy, Maev. "Alma-Tadema show includes most expensive classical Victorian piece." The Guardian. Web. 29 August 2017.

Paul, Joanna."Rome Ruined and Fragmented: The Cinematic City in Fellini-Satyricon and Roma." In R. Wrigley, ed., Cinematic Rome. Troubadour: Leicester, 2008: 109-120.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. "Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Modern City of Ancient Rome." Art Bulletin XXXIV.1 (March 2002): 115–129.

Created 3 September 2017