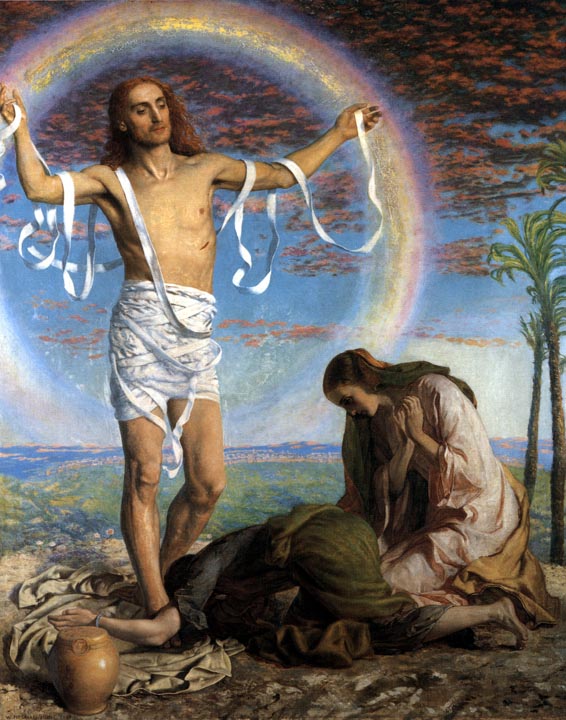

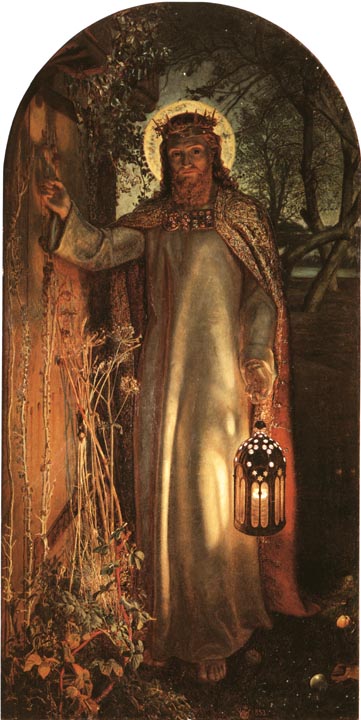

Left: Christ and the Two Marys. Right: The Light of the World. William Holman Hunt. 1851-53.>Oil on canvas over panel. arched top, 49 ⅜ x 23 ½ inches. Keble College, Oxford.

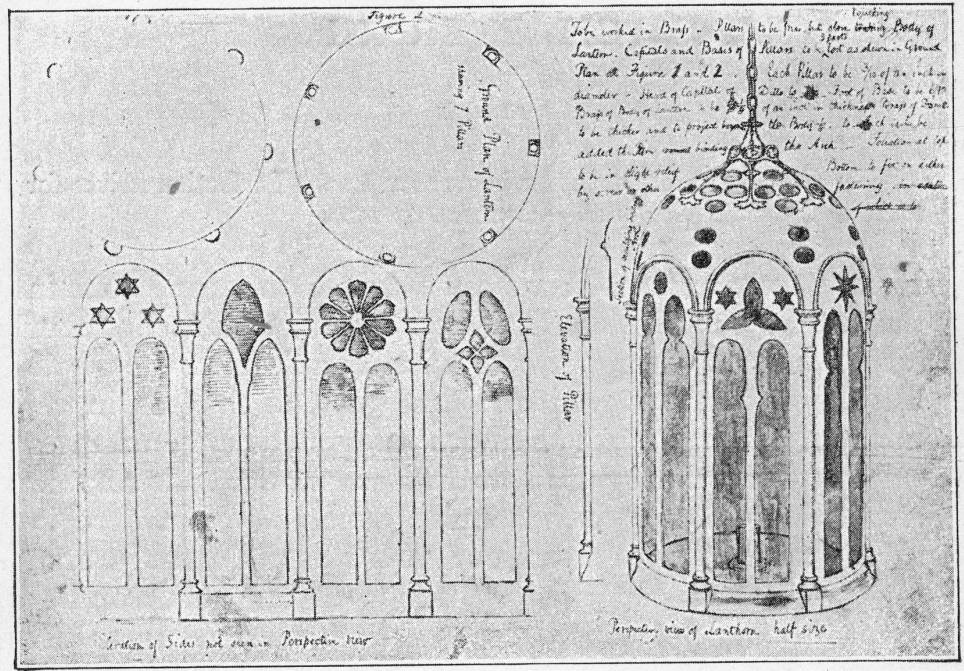

ccording to Hunt, he did not find solution to his combining an integrated form of symbolism with highly realistic painting in Christ and the Two Marys since he abandoned the picture when he realized it did not correspond to his beliefs. But when the text "Behold I stand at the door and knock" came as a response to his anxious religious questionings, he found that it brought a new symbolism with it. As the painter assured John Lucas Tupper, even the most basic visual elements of the painting had spiritual meaning for him. He painted the figure of Christ to emphasize solidity and mass because he wanted to avoid the implications of conventional religious art: "In England you know spiritual figures are painted as if in vapour. I had a further reason for making the figure more solid than I should have otherwise done in the fact that it is the Christ that is alive for ever more. He was to be firmly and substantially there waiting for the stirring of the sleeping soul." Hunt also conceived the lighting in terms of its spiritual significance — just as he was later to do in The Triumph of the Innocents . The figure of Christ, he explained, was "to be seen only by the light of the star of distant dawn behind, and of some moonlight in front with most of all the light "to guide us in dark places" coming from the lantern. This mixture of lights is all natural on the understanding that it is treated typically" (20 June 1878; London (Huntington MS.). In the world of religious vision which Hunt created in The Light of the World all things necessarily bear higher meanings, so that the symbolical and the natural combine: both together make up the real. although one cannot be certain about the precise significance of all elements of the picture's lighting , it is clear that Christ's lantern — whether it be the light of truth or of Christian doctrine — provides most of the illumination. The promise of a new day, a new life once the soul awakens to Christ, and the natural light of the moon can shed some, too, but Christ himself must be the chief means by which one can see him.

In Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Hunt explained the other points of symbolism in The Light of the World :

The closed door was the obstinately shut mind, the weeds the cumber of daily neglect, the accumulated hindrances of sloth; the orchard the garden of delectable fruit for the dainty feast of the soul. The music of the still small voice was the summons to the sluggard to awaken and become a zealous labourer under the Divine Master; the bat flitting about only in darkness was a natural symbol of ignorance; the kingly and priestly dress of Christ, the sign of His reign over the body and the soul, to them who could give their allegiance to Him and acknowledge God's overrule. In making it a night scene, lit mainly by the lantern carried by Christ, I had followed metaphorical explanation in the Psalms, "Thy word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path,' with also the accordant allusions by St. Paul to the sleeping soul, "The night is far spent, the day is at hand." (I.350-51)

Hunt's sketch for the lantern in The Light of the World. Source: Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. I, 308.

For the painter it was a matter of great importance that the iconography of the picture "was not based upon ecclesiastical or archaic symbolism, but derived from obvious reflectiveness." According to Hunt, his symbols "were of natural figures such as language had originally employed to express transcendental ideas" (I.350). In other words, he believed that The Light of the World created its symbolic language in precisely the same way that men had formed language to express abstract and spiritual ideas. The important point is that, since the symbolism derives from what he takes to be essential habits of mind, it would be immediately comprehensible to any audience, because such "natural" symbolism does not require any knowledge of iconographic traditions. Nonetheless, since his method was unusual, he had worked "with no confidence" that his symbols would interest anyone else. The fact that The Light of the World has "in the main been interpreted truly" without any additional assistance from him convinced Hunt that his method had been successful (I.351).

The almost astonishing popularity of this picture in nineteenth-century England and America appears not only in the fact that many took it to be the single most important contemporary portrayal of Christ but also in its influence upon popular poetry and book illustration. Like Tennyson's In Memoriam ,The Light of the World succeeded in reaching a large audience, eventually becoming an element of popular culture. The picture became known beyond the narrow confines of the art world by means of its engraved version, and it was popularized even farther by sermons and devotional poetry (See, for example, Richard Glover, The Light of the World;" or, Holman Hunt's Great Allegorical Picture Translated into Words, which, according to Fredeman, saw editions of 1862, 1863, and 1871.). Because Tupper was a close friend of the painter, one obviously cannot claim that his poem entitled "The Light of the World" exemplifies the picture's popularity; but its appearance in the 1855 Crayon suggests that many became aware of Hunt's subject, and the very fact that Tupper was moved enough by his friend's painting to write a poem about it suggests the effect it had upon many Victorians. The poem, which the editors accompanied by an extract from Ruskin's letter to The Times, astutely takes the form of a dream vision. The speaker relates how when walking in the night he came upon

a house whose door no hands disturb:

The ivy root had bit into the grain;

There had not been, or knife or hand to curb,

Where grew the rankest thing, that would attain

Its natural will. [87]

At this point the speaker has a vision of Christ knocking at the door, and he awakens with a start. Later that night when sleep returns, he again encounters the figure of Christ "walking round/The darkness with that most miraculous light,' and he concludes that anyone who has not been blessed with the same vision "hath slept too sound" (87). although Tupper is not a first-rate poet, he felt the power of the painting enough to attempt a transformation of the image into an imaginative vision.

Most of the poems which demonstrate the influence of Hunt's painting do not even rise this far from the ordinary, and they are of more interest as examples of popular culture than powerful influences of painting upon her sister art. Robert H. Baynes'sThe Illustrated Book of Sacred Poems (1867), an Anglo-American venture, exemplifies the way The Light of the World had an influence upon popular doctrinal works and hymnals, and through them became known to members of the lower and middle classes. W. Chatterton Dix's "Behold, I Stand at the Door and Knock!" acknowledges in its subtitle that it was "Suggested by Holman Hunt's "Light of the World'" (164), but several other references to the lines depicted by Hunt do not. Harriet McEwen Kimball's "The Guest" (336-37) simply narrates the sinner's encounter with Christ who comes to the door and knocks, and Alan Brodrick's "Pity Me, Lord" seems to draw upon both Hunt's painting and Tennyson's "Palace of Art":

But ah! wert Thou all night outside my door,

And I so noisy with love's selfish fears?

Why heard I not Thy patient knock before,

As the dull lamplight flickered through my tears?

Pity me, Lord, I am a little child.

Come in, my Lord, I dread to be alone,

My fairy palaces are lost in dust. [80]

In the decades following the first exhibition and engraving of The Light of the World poets continued to draw upon it for imagery. In The Song of the New Creation (New York, 1872), Horatio Bonar, a Scottish writer of popular devotional poetry, made use of Christ standing outside the sinner's door in "The Drops of the Night," while an anonymous poet published "Behold, I stand at the Door" in the 1875 Good Words, a periodical with which Hunt was associated" (25 [1875], 557). Both Joseph Grigg's hymn "Behold! a Stranger's at the door!" (1765) and Longfellow's translation of Lope da Vega's sonnet using the same image anticipated Hunt's painting, but The Light of the World was responsible for its Victorian popularity.

W. H. Fisk, illustration to Kimball's "The Guest." (Right) W. Rainey's Christ before thy door is waiting.

Equally revealing is the fact that Hunt's painting entered the realm of popular religious illustration. W. H. Fisk drew upon The Light of the World for his picture which accompanied Kimball's "The Guest,' and Hunt was also the clear source of W. Rainey's Christ before thy door is waiting in William Adams's Sacred Allegories. In each case, it was Hunt's representation of Christ standing outside the door of the human heart or outside man's earthly dwelling which attracted the illustrator, and one must be careful not to draw the conclusion that each one of them understood all the details of his iconography. Nonetheless, since the poets reveal that they grasped Hunt's intention, it seems likely that the painter was completely correct when he claimed The Light of the World had been generally understood by his contemporaries. Where Hunt's work differs from that of Coleman, which also illustrates various biblical texts about the Saviour, is that, whereas the Bristol painter assembled a group of separate images, Hunt created one image incorporating the various texts. Hunt believed, and he seems to have been correct, that if one meditated upon his vision of Christ the meaning of all its details would gradually become clear. One value of such an integrated symbolism, therefore, is that if the painter can make his main intention clear, then the details will follow from it fairly easily.

The Light of the World could not solve all of Hunt's problems in reconciling realism and a religious iconography, since, as he himself recognized, it was unique in his career. In the first place, it recorded spiritual truths in the form of a vision; he was not primarily interested in painting such visionary subjects, and he did not like to repeat himself. Secondly, this work derives from a very personal, not easily repeated experience of conversion, and it could not therefore provide the more general answer for which he was seeking. Nonetheless, The Light of the World was a turning point in Hunt's career — one of many — because it did demonstrate for him that he could combine realistic style, imaginative vision, and a religious iconography in a form accessible to others. Equally important, it marked a new faith which would later allow him to employ typological symbolism as a basis for his religious realism.

Details and related material

- Manchester version

- Later St. Paul's version

- Christ's lantern (St. Paul's version)

- Study for the lantern

- Christ's head and the typological breastplate (St. Paul's version)

- Words inscribed on frame (St. Paul's version)

- Vegetation (St. Paul's version)

- Copies in other media

Bibliography

Landow, George P. "Shadows Cast by The Light of the World: William Holman Hunt's Religious Paintings, 1893-1905." The Art Bulletin, 64 (1982), 646--55

Landow, George P. Replete with Meaning: William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979.

Maas, Jeremy. Holman Hunt's "The Light of the World". New Haven and London and Berkeley: Scholar Press, 1984.

The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Gallery/Allan Lane, 1984.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Seven Dials, Cassell & Co, 2000.

Last modified 26 December 2021