In transcribing the following article from the Hathi Trust online version of a copy of the Illustrated London News in the Princeton University Library, I have used ABBYY software to produce the text below. The original article places places the plan of the excavations to the right of the column in which “Recent Assyrian Discoveries by Mr. Rassam” begins, and the all other illustrations appear on a single preceding page. I have placed them near the points in the article that discusses them, and I have added paragraph breaks for easier reading. — George P. Landow

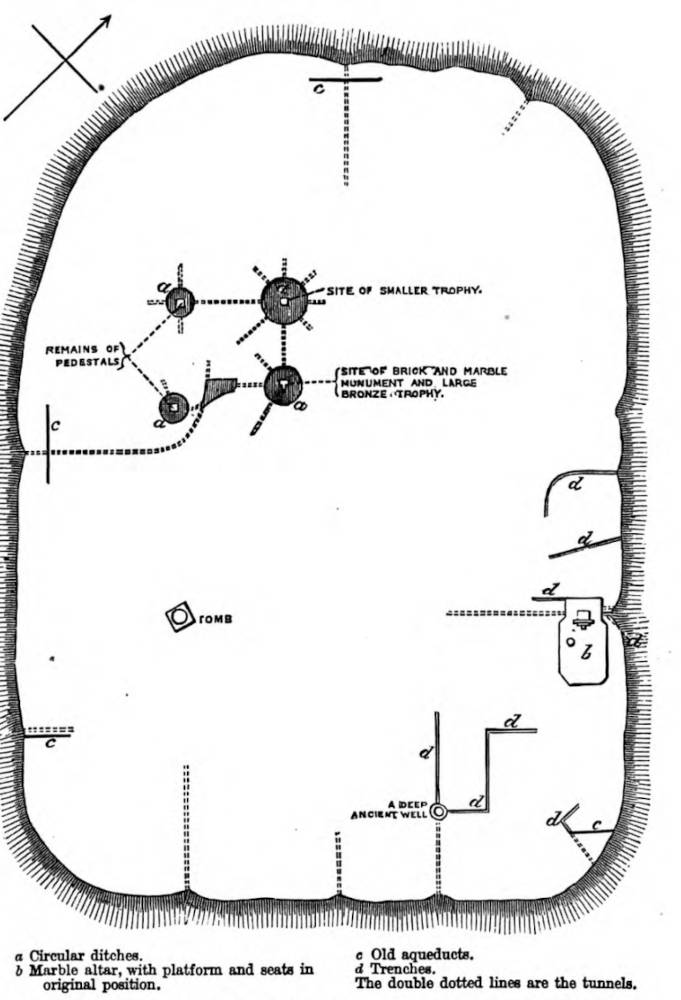

Plan of Mr. Rassam’s Excavations in the Mound at Balawat. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Some interesting articles in the Times, and in several other dally journals, towards the end of last August, described the important discoveries made in the spring of this year by Mr. Hormuzd Rassam at Balawat, nine miles north-east of Nimroud (Kalakh), and fifteen miles from Koyunjik, on the Tigris, the site of ancient Nineveh. Mr. Rassam, a native of that country, but a naturalised British subject, and long in the service of our Foreign Office, was the assistant of Sir Austen Henry Layard, now her Majesty’s Envoy at Constantinople, in the famous explorations of Nineveh and Nimroud, about thirty years ago, which contributed the first instalment or relics of the Assyrian historical monuments to the British Museum. Since the lamented death of Mr. George Smith, who had carried on the work partly for the British Museum, partly at the cost of the proprietors of the Daily Telegraph, the Museum authorities have commissioned Mr. Rassam to pursue these researches, from which he has already obtained some valuable results. He came home last summer, bringing some collections which are now in the Museum, and a portion of which, from Balawat, are the subject of our present Illustrations.

A lecture explanatory of these sculpture-records of Assyrian history was delivered last week to the Society of Biblical Archaeology, in Conduit-street, by Mr. Theophilus Pinches, the successor of Mr. George Smith at his post in the Oriental Antiquities Department or the Museum. He described the mound of Balawat as the site of an ancient Assyrian fortress, which had borne a different name before the reign of Assumazirpal, father of Shalmaneser II., whose reception of tribute from Jehu, King of Israel, is recorded on the famous black obelisk. Though so close to Nineveh, it had been taken and held by the Babylonians during a period of Assyria’s political decline, perhaps coincident with the epoch of Hebrew ascendancy. But when Assumazirpal, a great warrior, came to the throne he recovered the city, and renamed it Imgur-Beli, and built there a temple to the god of war, near the city’s north-eastern wall. These facts are recorded on alabaster tablets found by Mr. Rassam in a coffer of the same material near the entrance of the temple itself. As Mr. Pinch remarked, they shed a fresh ray of light on one of the darkest periods of Assyrian history.

The mound is nearly rectangular, and its corners are turned pretty accurately towards the four cardinal points of the compass. The temple ruins lie near the north-eastern edge, where ran the city wall. In the western half of the mound four stone platforms were found marking the sides of an irregular square. While digging round these platforms Mr. Rassam unearthed some pieces of chased bronze, and at length two huge bronze monuments slowly came to view. They were of the strangest shape. Each seemed formed of a centrepiece with seven long arms on either hand, like colossal hat-racks, with which the first published accounts compared them. Even after laying them bare, the energetic excavator had great difficulty in disinterring them, and was mortified at hearing the precious bronzes split and crack as the sun dried up the earth in which they had lain buried during so many centuries. According to the explorer’s ground plan, the platforms mark the entrances to the courtyard of a noble palace, having two entrances on the north-east and two others on the north-west. The bronzes arrived at the British Museum at the beginning of August last. There they met with an enthusiastic welcome, and no less naturally called forth much speculation as to their nature and use. To Mr. Ready, the ingenious artificer of the department at the British Museum, whose task it was to see to the cleansing of the fragments, piecing them together, and nailing them with the original bronze nails on wood of the same thickness as that which underlay the plates thus fastened, belongs the merit of solving the riddle. He was the first to see that the bronze plates of the larger of the two monuments haa formed the coverings of an enormous pair of rectangular folding doors, each about twenty-two feet in height and six feet broad, which had evidently turned on pivots, and were held up at the top by strong rings fixed in the masonry. The body of the doors was of wood three inches thick, as measured by the nails, which are found to be clinched a little more than that distance from the heads, the overplus being just the thickness of the bronze plates themselves, which is about pne sixteenth of an inch. Each door revolved on a circular post, about a foot in diameter. Each post had a pivot at the bottom. The pivots are at the Museum, but the sockets in which they turned were unfortunately left behind. The bronze plates are about eight feet long. They were nailed horizontally across each door, but, allowing for their extension round the post, the total length across each leaf was but six feet. What is technically termed the “style” of each leaf was also overlaid with a bronze edging, which overlapped the door by about a couple of inches. On the right it is cut plain, but is indented on the side overlapping the back of the doors. The smaller pair of gates is much more decayed than the other. Its designs represent hunting scenes, and it belongs to the same reign as the larger, whose inscriptions are those of Shalmaneser II. The representations on the plates of both pairs are in the repoussé style.

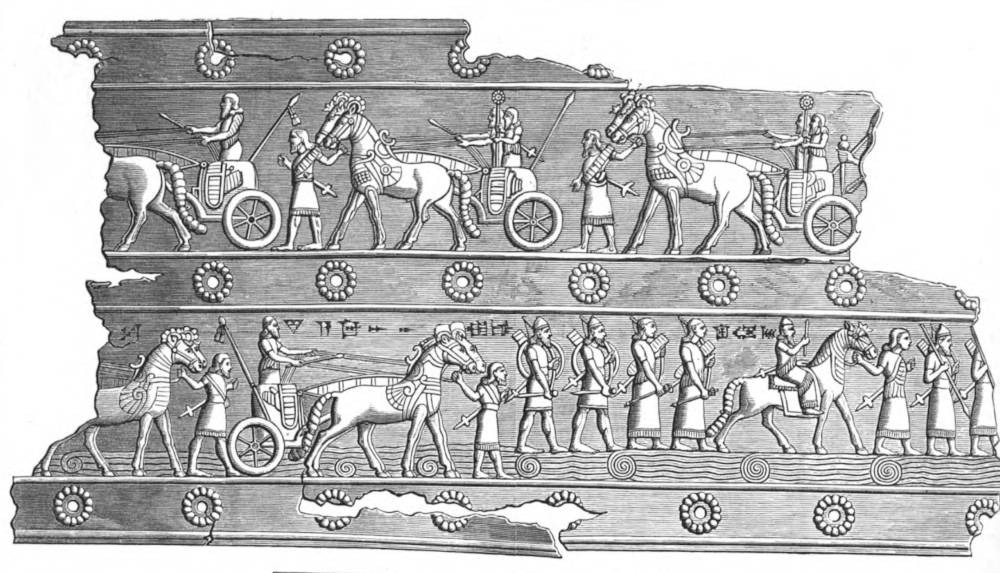

Bronze Sculptures of gates in the Temple at Balawat, Near Nineveh. “The bronze sculptures . . . show the King with his army on the march; warriors standing in two-horse chariots, like those of Homer's heroes at the siege of Troy, the horses led by footmen; the King riding on horseback, wearing a loose robe and cap, with attendant eunuchs before and behind him, and men carrying his bows and quivers, wading across the River Tigris.”

Those on the plates of the great gates depict Shalmaneser’s battles, sieges, triumphal processions, the tortures inflicted on his prisoners, and his worship of the gods. The bronze plates covering the “styles” of the doors are also engraved with historical inscriptions, of which, reserving for another time his account of the extremely numerous and interesting designs chased on the doors themselves, Mr. Pinches gave the general purport. The record on the “styles,” he observed, though somewhat fuller than that on the black obelisk, and than the Kurkh and Bull inscriptions, is very carelessly executed, even the chronological order of events having been to some extent inverted. The new document begins with Shalmaneser’s Babylonian campaign, when he went to help King Mardukn-Suma-Iddin against that Babylonian Monarch’s revolted brother. Next, it places his war in the region of Mount Ararat, followed by that against Gozan, and his triumph over Akhuni, King of Borsippa, which paved the way for his conquest of Syria and Palestine. A critical comparison of all the sources proves, however, that the Ararat campaign came first, and then his expeditions against Akhuni and the Babylonian war. In concluding, Mr. Pinches held out the hope of identifying, in his future paper on the bas-reliefs (which greatly exceed in number those in the Nimroud Gallery in the British Museum), some Jewish faces of the ninth century before Christ. It is certain that, as he remarked, this wonderful monument cannot fail to be of great use to the ethnologist, as well as to the philologist and the antiquary.

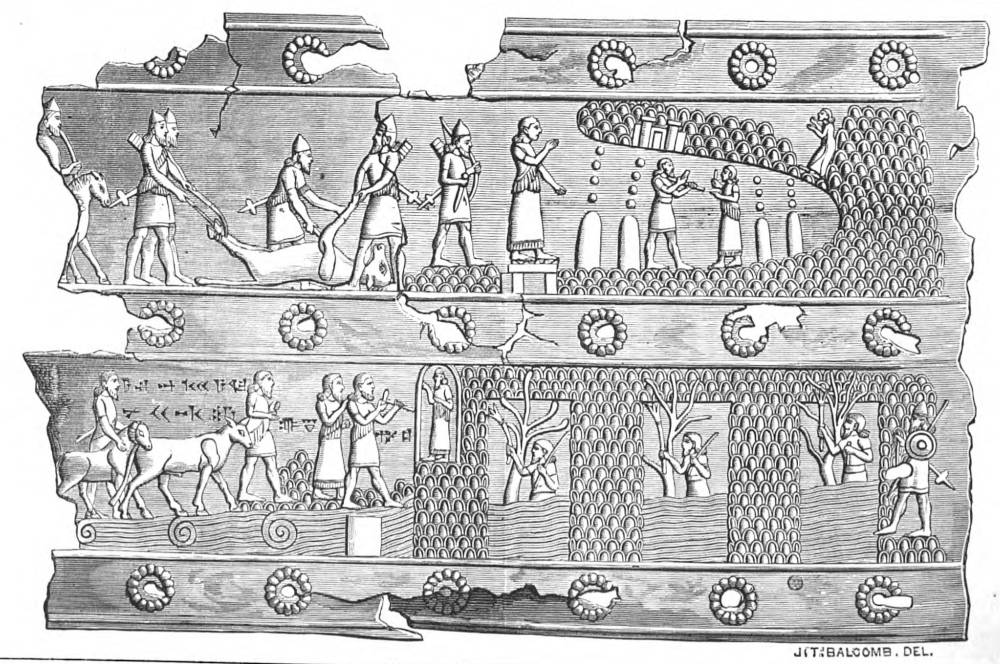

“The King appears standing to offer sacrifices upon an altar; the captain of his guard is behind him, with soldiers who are bringing a slaughtered bull and a live ram for the offering. There are four conical stones, the well-known emblems of a common object of Eastern nature-worship; there is a sacred grove of trees, with a lodge or temple in the background”.

The late Mr. George Smith’s excellent summary of the “History of Assyria,” published by the Christian Knowledge Society, tells us the events of Shalmaneser II.’s reign, from b.c. 860 to b.c. 824. He continued and maintained the conquests of his father Assur-nazir-pal, the builder of the palace at Nimroud, who had marched his army to the Mediterranean seacoast, and exacted homage from Tyre and Sidon. The military expeditions of Shalmaneser II. likewise conducted him into Syria, and led to the series of conflicts related in the Second Book of Chronicles, in which Israel and Judah became fatally involved, but at a considerably later period. This circumstance gives a share of Biblical interest to the actions delineated in the bronze sculptures of which we present some Illustrations. They show the King with his army on the march; warriors standing in two-horse chariots, like those of Homer's heroes at the siege of Troy, the horses led by footmen; the King riding on horseback, wearing a loose robe and cap, with attendant eunuchs before and behind him, and men carrying his bows and quivers, wading across the River Tigris. Then, in the piece below, the King appears standing to offer sacrifices upon an altar; the captain of his guard is behind him, with soldiers who are bringing a slaughtered bull and a live ram for the offering. There are four conical stones, the well-known emblems of a common object of Eastern nature-worship; there is a sacred grove of trees, with a lodge or temple in the background, and the guardian priest is talking with the King’s herald or secretary, who may perhaps be asking leave to approach or enter the sanctuary. The nethermost scroll would seem to represent the King’s servants cutting an inscription on the rock, and lopping a fiw branches of the trees, to commemorate his visit to the foreign shrine. This was situated, most likely, in Northern Syria, and there would be a motive of policy for thus recording the pious regard of Shalmaneser for the divinities worshipped by the nations over whom his ambition sought to reign.

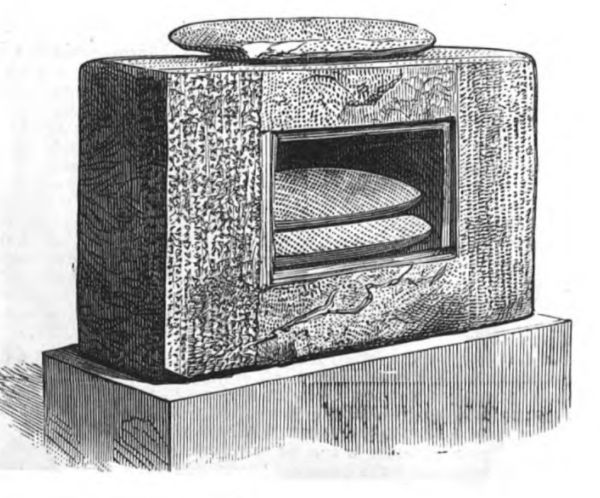

The alabaster chest, three feet long and two feet high, which contained three alabaster tablets, all covered with inscribed history of the reign of Assur-nazir-pal, is represented at the top of the page. A ground-plan of Mr. Rassnm’s excavations at Bulawat is also furnished, and we may expect the publication of his own account of them, as well as Mr. Pinches’ further interpretation of their historical import.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Hathi Trust and Princeton University. (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

“Recent Assyrian Discoveries by Mr. Rassam.” Illustrated London News (16 November 1878): 464-66. Hathi Trust online version of a copy of the Illustrated London News in the Princeton University Library. Web. 8 May 2021.

Last modified 8 May 2021