In transcribing the following article from the Hathi Trust online version of a copy of the Illustrated London News in the Princeton University Library, I have used ABBYY software to produce the text below to which I have added paragraph breaks for easier reading. — George P. Landow

Lincoln, the ancient capital of Mercia, can carry back its history to a period still more remote than that of the Heptarchy. Its commanding position seems to have recommended it to the invading urmy of Claudius, and there is little reason to doubt that it became a powerful Roman colony before the first century of our era. Indeed, its name, which is only slightly fused down from “Lindum Colonia,” sufficiently attests its antiquity, and lends an additional interest to the very numerous traditions that connect the city with the most prominent events and characters of English history. Originally “a city set upon a hill,” and commanding an almost unequalled vantage-point against an approaching foe, it has gradually ventured to descend from its eyrie, and from time to time building on the steep and once nearly inoccesssible escarpment, a large portion of it now nestles securely on the plain, under the shadow of its majestic Cathedral. In few even of our most ancient cities does the contrast between the past and present more vividly suggest itself than in the city of Lincoln. From whichever side we approach it, its noble minster stands forth as a prominent object for many miles around; and as we arrive upon the river-banks below, the ring of its world-renowned foundries, incessantly at work, and puffing from their tall chimneys the smoke which yet falls short of the height even of the Cathedral floor, forms a strange contrast to the solemn stillness and dignified repose of the lofty fane that crowns the hill.

The most ancient part of the city is that which is familiarly called “Above Hill,” where there is a rich abundance of material for the artist, the architect, and the antiquary. At the northern entrance from the ancient Ermine-street, that led through Lincoln to Yorkshire, is the celebrated Newport Gate, a genuine Roman relic, and probably a unique example of so ancient a fabric retaining its original use. It evidently was much loftier, and was Hanked by two posterns, only one of which remains at the present day. The gate is of stone, and its solidity and strength, after the lapse of eighteen hundred years, and, possibly, after very many assaults, attest the marvellous constructive skill of a people who believed themselves and their works to be eternal. Not far from this is an interesting ruin, of the same massive character, called the Mint Wall, and the numerous relics, and even the configuration of the ground, combine to bring vividly before the mind the reality of the traditions with which this spot is connected.

Only second in grandeur, and equal in its commanding position, is the Castle of Lincoln, built, with seven other fortresses in various parts of England, by William the Conqueror, and long used as a favourite residence of the early Norman Kings. It now contains within its precincts the County Hall, where the assizes are held, and its necessary complement, the County Gaol. At the north-east corner there stands a building of ill omen, called Cobb Hall, where, until the recent Act, public executions took place. The two most interesting features of the Castle are the keep and the eastern gate; the former still towers over the city in solid grandeur, though its upper portion has long fallen a prey to time or to the numerous assaults it has undergone; while the latter, which opens on the Castle-hill, and so faces the western entrance of the Cathedral, is a singularly imposing structure, containing some fine Norman work. In the Castle yard there is a beautiful oriel window, which of late years has been removed from the ruins of John of Gaunt’s palace. This princely abode was built in the lower part of the city for his third wife, Catherine Swinford, to whom, in 1396, he was married at the high altar of Lincoln Cathedral, to which he presented a pair of golden candlesticks. His bride, though not of Royal birth, was the ancestress of Henry VII., and so, in the Lancastrian line, of the present Royal family of England. She was a sister of the wife of the poet Chaucer.

Little now remains of the mansion of “time-honoured” Lancaster and his fair spouse, though it must be owned that the hand of Vandalism has not been so busy here as in most places, for almost every street attests the care with which the relics of the past have been preserved. Debemur morti nos nostraque. Time will do its work upon “the stateliest building man can raise.” The good knights are dust who once joined in the pageants of the city or fought beneath its walls. It is something that the fame of men, for good or evil, is more lasting than their houses, and that we can people the crumbling ruin or the historic locality with the greatness or the littleness that perished long ago. If, with Æneas and the Sibyl, we could pass within the ivory gates and see the shadowy forms of those who once lived and loved, and quarrelled and fought, and feasted and junketed here in the olden time, what a noble array of those who have left their record in Lincoln would pass before the view! Romans, Britons, Saxons, and Danes would arise, as when they struggled for the possession of the walled city on the hill-top: for here Cridda of Mercia rebuilt the ancient town by the Newport Gate, and here Paulinus preached to heathen Saxons, and first built a Christian church. Here, too, the terrible Dane destroyed the Saxon burgh; and, later on in time, impressed his mark of conquest over all Mercia in his unerring “byes,” which tell, more truly than any history, where the Dane once dwelt in undisputed power, calling the land after his own names. Here William the Norman, after crushing all his foes, pounced upon the hill as one of the most convenient spots for keeping watch and ward over his new conquest: for the men of the fens were no mean foes, as Hereward had taught him to his cost in the Isle of Ely. And, moreover, by this time Lincoln had become one of the foremost towns in England, and already could boast of fifty-two parishes within its precincts. What impression the Norman occupation of the Castle produced upon the city may be seen in the present day by the countless fragments of their massive and elaborate architecture, which are built into and incorporated with the modern buildings. There are few streets where some remains of a Norman arch or other decoration of that period is not to be met with. The two Engravings taken from each side of the bridge which crosses the High-street exhibit specimens of the prevailing architecture, which is even more conspicuous under the bridge in the crypt-like roof and the interlaced semicircular arches whi(m span the river Witham—the Lindis of Jean Ingelow’s exquisite poem.

Old Houses.

Very quaint is the antique wooden house which is built over the western front of the bridge, and, with the surrounding block of buildings, rather resembles a nook of some old German town than the back of the chief street of an English cathedral city. However picturesque it may be, it has a dark and gruesome look, which, combined with the long, tunnel-like, and gloomy vault below, seems to suggest some other motive than beauty or sanitary exigencies for its continued preservation. At present it has a damp, moist, and unpleasant appearance; and it would require a very vivid imagination to conjure up that particular period in its past history when, no doubt, it appeared to its owner to be dry, bracing, and cheerful.

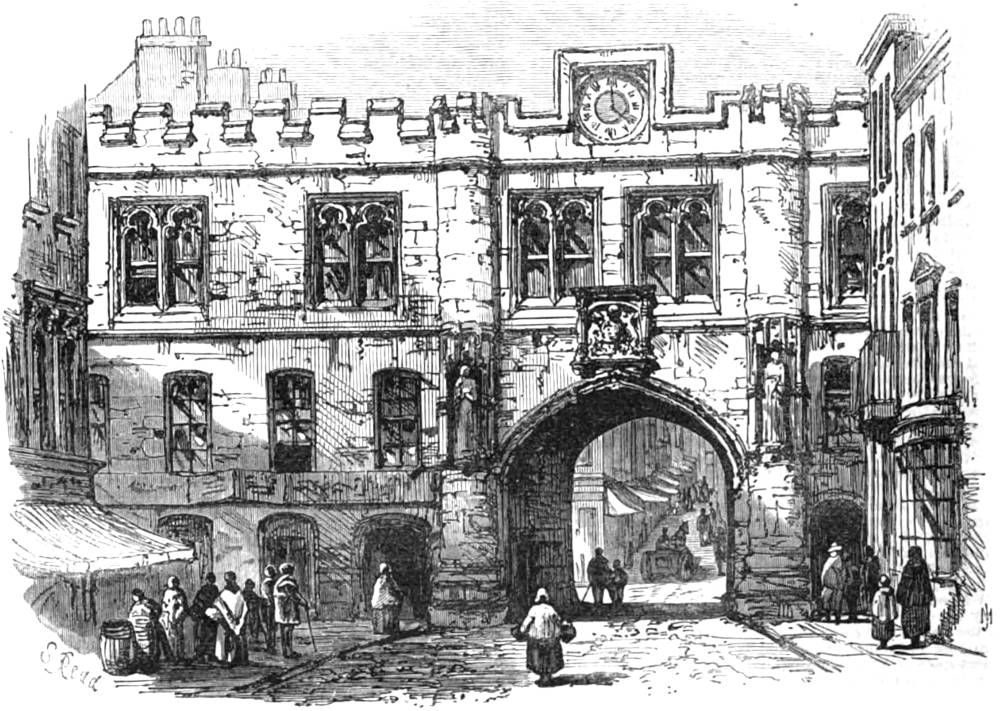

Stone Bow.

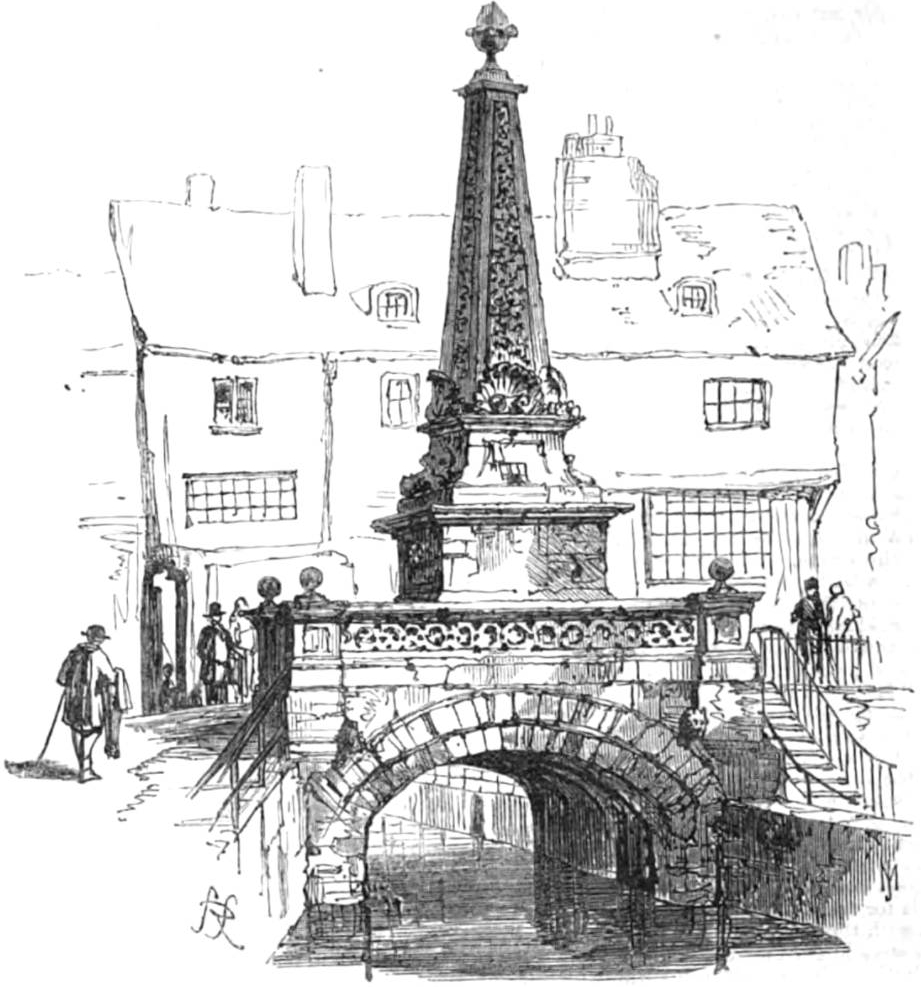

The obelisk over the east front of this bridge was erected about a century ago, above a conduit which formed the one of the water supplies of Lincoln in former times. It is connected with a very elegant structure called St. Mary’s Conduit, of which we give an illustration. This Conduit is one of the chief ornaments of the lower part of the city, where, however, trade is carried on, and the enterprise of the present — represented by railways, foundries, and markets for every kind of agricultural produce—has little time or inclination for the aesthetics of ancient art. Yet few, upon whatever errand bent—can visit Lincoln without casting one glance of interest upon the Stone Bow or gateway, which may be said to separate the ancient from the modern town. It is as much the characteristic feature of Lincoln as Las Grosse Horloge is of Rouen, though from its with and handsome proportions far surpasses the Norman archway. The View engraved, taken from its south front, shows it to be a Battlemented structure, of which the upper part is in the Tudor gothic of Henry VIII. The arch with its two posterns, and the lower part of the building, are of a somewhat earlier date. The interior is used as the Guildhall, and consists of an antique chamber fitted up as a justice-room, and of other offices. The whole building forms a striking and interesting object, and adds greatly to the picturesque character of the city of Lincoln.

Left: The Obelisk. Right: The Jews’ House. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passing through the Stone Bow, we begin to ascend the hill on which the Cathedral stands, and as we toil up the acclivity, which in one part is so steep that some compassionate soul has provided a hand-rail to help passencers on their way, we pass, on the left-hand side, one of the lions of Lincoln—the Jews’ House. The house itself exists no longer, but a large portion of the facade still remains. This consists, as in the Engraving, of an ornamented Norman doorway, surmounted by a chimney-gable, from the interior of which, however, the ancient fireplace and mantelpiece have been removed. The exterior still retains traces of a Norman mansion, and such, in its beet days, this Jews’ House must have been. It is said to have been once inhabited by Belaset de Wallingford, a Jewess, who was executed in the reign of Edward I. for clipping the coin of the realm—shearing the flock which bred so fast for Shylock. It is a singular fact that in more than one of our towns the few remains of Norman domestic architecture should be connected by popular tradition with the Jews. There is, however, no reason to doubt that the Jews of Lincoln were both numerous and wealthy, and probably for the latter reason were accused of the most atrocious crimes, to give their needy oppressors an excuse for confiscating their property. In the thirteenth century no less than eighteen Jews were executed on a charge of having crucified a child, called afterwards St. Hugh. This, in the Middle Ages, was devoutly believed to be an annual and regular custom with the Jews, and the story is told by Matthew Paris in all seriousness how that a Jew of Liucoln—one Copin by name—inveigled this Christian child Hugh into his house, and secretly sent invitations to all the Jews in England to be present at the crucifixion of his victim. Copin, under the influence of the rack or a promise of impunity for himself, confessed that others had committed the crime, and acknowledged that it was an annual occurrence. A ballad called “Hugh of Lincoln” is still extant, which enters into the details of this pretended crime. Chaucer repeats the horrid story in one of his “Canterbury Tales.” It is not surprising, however, that these excuses should have been made for destroying and plundering the Jews, when we find, from a note to Hallam's “Middle Ages,” that it was a custom at Toulouse to give a blow on the face to every Jew at Easter, which was liberally commuted in the twelfth century for a regular tribute; whilst at Beziers, in the south of France, another usage prevailed—that of attacking the Jews’ houses with stones from Pahn Sunday to Easter. No other weapon was to be used, but it generally produced bloodshed. The populace were regularly instigated to the assault by a sermon from the Bishop. At length, we are told, a prelate wiser than the rest abolished this ancient practice, but not without receiving a good sum from the Jews. The raison d’ être of these Norman strongholds for the Jews’ houses in mediaeval times may not be unconnected with these popular, not to say episcopal, pastimes.

But the steep hill of Lincoln brings us again to the noble esplanade on which the Cathedral stands, and, turning to the right, we pass under a collegiate-looking gateway and find ourselves before the west front of the renowned Lincoln Minster. York may surpass it in size, the cathedrals of Normandy may be more elaborate in some of their details or more incrusted with minute embellishments; but for simple and stately grandeur, for general tone and harmony, for compactness and just proportion, it is hardly too much to say that Lincoln is unsurpassed by any cathedral in the world. It is beyond the purpose of the present sketch to enter into any elaborate discussion of its architectural features, or to do more than speak of its general effect, as no description can convey to the eye the blending of its numberless forms, the softness of its various lights, and the unity in diversity of its several parts. It owes its origin to an order which was given towards the end of the Conqueror’s reign that all sees should be removed to fortified towns. In consequence Remigius de Fécamp, a Norman, was transferred from Dorchester to Lincoln, and at once, in 1085, commenced the building of a cathedral near the Castle. This was completed and consecrated shortly after his death, in 1092, in presence of all the Bishops of England, except Herbert Lozinga, of Hereford, who declined to come, on the plea that his errand would be useless, as he had learned from the stars that Remigius would be dead on his arrival. It is not impossible that the communication of such a message to an old man in a very superstitious age might have led to the fulfilment of the prophecy. Certain it is that Remigius died as predicted. The work which he had thus begun was continued by his successors, who made additions of the most munificent kind; and in one instance, Hugh, of Grenoble, who was Bishop from 1186 to 1200, is said to have “shouldered the hod and worked with his own hands” in the building of the Chapter-house. He was canonised after his death; and, as St. Hugh of Lincoln, his shrine was only less celebrated than that of his contemporary, St. Thomas of Canterbury.

After many alterations and additions, especially that of the present central or Rood Tower, which was begun by Bishop Grosttete, in the middle of the thirteenth century, and finished by Bishop d’Alderley, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Cathedral was completed as it now stands, the pride and glory of the shire and city of Lincoln. Originally its towers were surmounted by spires, one of which was blown down in 1547, and the other two were removed, though not without serious opposition, in 1808. It is interesting, in investigating the history of these magnificent cathedrals, to find that they were reared by the munificence of the lordly bishops of former times. If their revenues were princely, and their palaces such os vied in magnificence and luxury with the baronial halls and feudal castles of the highest nobility, it was consistent with the position they assumed to take care that the temple of their Maister should infinitely surpass in durability and grandeur the stately mansions they erected for themselves. Whilst the palace of the Bishops of Lincoln lies in ruins at its feet, the Cathedral stands as erect and solid and four-square to all the winds th*t blow as if it had just come crisp and fresh from the builder's hands and had a thousand years’ work before it. As we gaze upon such a fabric as this, it suggests that, after all, there was a something real and vital about the piety of the Middle Ages, and that, as Wordsworth says, “they thought not of a perishable home who thus could build.” One may well be excused for expressing an unbounded admiration for this almost matchless pile. Some objection has been made to the west front that it forms a species of screen and conceals from view the purpose of the two western towers. Though there is something in this, yet, even if it be a screen, it is so full of elaborate detail and is so grand in itself that it carries its own defence on its face. The immense proportions of the arch that contains the central door and the west window, flanked as it is by two others which are only small by comparison, form a fitting portal to the vast area within, and seem emblematic of the broad invitation to all to come in. The beautiful octagonal towers which bound the western front would be great if they were not reduced by comparison with the two western to were, which rise above them, in their turn to be diminished, though in harmonious proportions, by the vast central tower, which is the crown and glory of this noble edifice. Here is hung the Great Tom of Lincoln, though not the actual bell which received from old Fuller the quaint name of the Stentor of England. The present bell is even larger than the former, aud weighs five tons eight hundredweight, with a height of six feet, and a diameter at the mouth of nearly seven feet.

The ornamentation of the central tower is of the richest and most lavish kind, and everything connected with the exterior of the Cathedral is a fitting introduction to the grandeur of the interior, where almost every portion presents the same freshness and beauty as in the outer fabric. Nave, transepts, aisles, and choir show how the plainness and massive solidity of the Norman church have gained by the successive alterations in grace without any sacrifice of stability. Though the dimensions are vast and the utmost power of masonry is there, yet, the whole is rendered so light and almost aerial by the constant introduction of grouped columns that the eye is relieved from any feeling of oppressiveness. The triforium and clerestory of the nave, in themselves extremely light, lead up to even greater elegance and more elaborate detail in the choir and Lady-chapel, the whole being warmed and beautified by the large number of stained glass windows with which the cathedral abounds, from the well-harmonised east wTindow to the ruby light that streams from the clerestory. Nor is the spectacle less striking in the evening, when the choir is lighted up with beads of gas along the triforium, as it was one evening last week, when a very large assemblage gathered together to hear a stirring appeal on behalf of the County Hospital, and when every spot in that magnificent choir, with its matchless stalls, was occupied, as the Halliluah Chorus, grandly rendered, reverberated through the mighty falbic and thrilled the heart with gratitude to the Great Giver of all, and with pity for the suffering and the poor. [565-66]

Bibliography

"Leaves from a Sketchbook: Lincoln." Illustrated London News 53 (4 December 1868): 565-66. Hathi Trust online version of a copy in the Princeton University Library. Web. 30 May 2021.

Last modified 30 May 2021