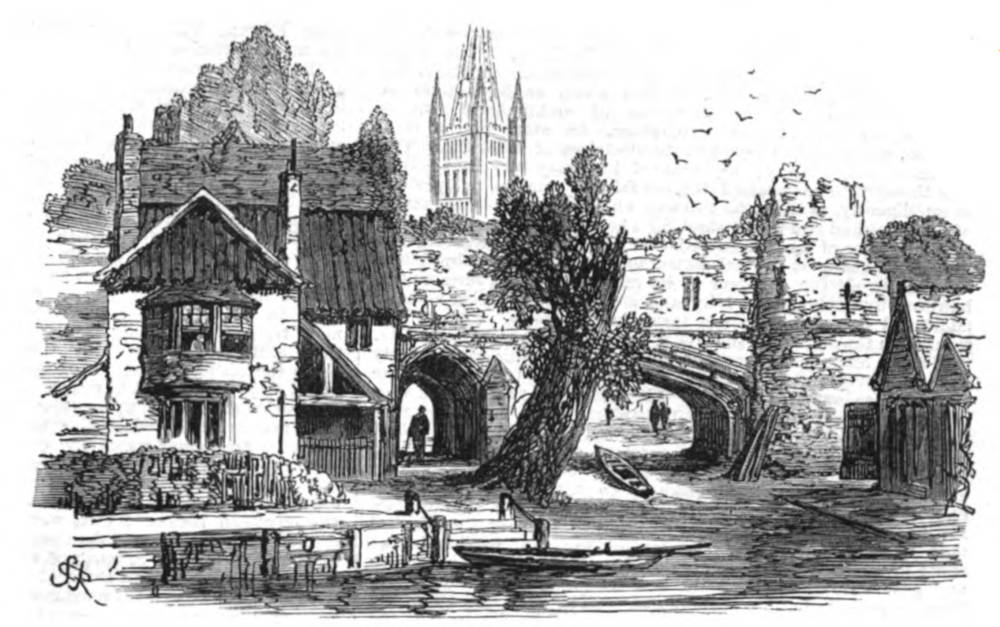

The Ferry. S. Read. 1868. Source: the 1868 Illustrated London News. Click on image to enlarge it

he city of Norwich, though it cannot lay claim to any very remote antiquity, has a noble and commanding appearance, and, if only for the sake of its magnificent cathedral, would well deserve notice and illustration in our Sketch-Book. Like the gentleman who could not speak German himself, but had a brother who could play the German flute, Norwich, if not ancient itself, is very near the site of one of the oldest cities of Britain. Its very name seems to imply that it is the northern town of some still more ancient foundation. This is really the case; for a few miles to the south of tho city stood the old fortified inclosuro of Castor, which was the Venta Icenorum of the Romans, and formerly was the capital of the heroic race who followed to hopeless slaughter the British warrior-queen Boadicea. It is not unlikely that it was from the ruins of Castor that the more modern city of Norwich arose on the banks of the Wensom, not far from its confluence with the Yare. It attained to some note during the later Saxon period, as is shown by tho fact that it was of sufficient importance to attract tho regards of the Danish King Sweyn, who, in one of his raids, incontinently burnt it to the ground. It soon, however, got over this misadventure, and with tho phoenix-like vitality of most of the ancient, and at least some of the modern, victims of a fire, it rose from its ashes more populous and prosperous than before. In Edward tho Confessor’s time it was wealthy enough to pay a considerable sum of money by way of tribute to the King, and was also compelled to furnish, for the recreation of that anything but “merry monarch,” “a bear and six dogs to bait him.” The last item shows an early sense of the final cause of a bear’s existence as well as a thrifty desire that he should not be wasted. To Matilda of Flauders, wife of tho Conqueror, the city of Norwich had to furnish, in addition to a considerable black-mail to her husband, a more appropriate tribute in the shape of an ambling palfrey. The resistance offered by the East Anglians to their new master involved Norwich in serious troubles during the reign of William, and it was not until the end of the reign of Rufus that tho transfer of the episcopal see from Thetford raised Norwich to tho front rank among the cities of England. In 1096 the cathedral was begun by the first Bishop of Norwich, Herbert de Losinga, who also erected the palace, wliich, renewed and restored from time to time, still stands in the northern precincts, and is the residence of his modern successor. . . .

The Norwich of the olden time must have presented a very imposing appearance, surrounded, as it was in the time of Edward III., with an embattled wall three miles in circumference, which was entered by twelve gates, and supported and embellished by no less than forty towers. Orchards and gardens surrounded many of the houses in this spacious inclosuro; and, in addition to the cathedral, there were at a subsequent period about thirty-seven churches. Of these St. Peter’s Mancroft, erected in the fifteenth century, is still a noble edifice, and stands out conspicuously from all the other churches of Norwich. A city so prolific in churches might expect to be distinguished for the eminent ecclesiastics it has produced, and it will be found to have contributed its fair ouota to the list of English worthies. Not to mention Herbert de Loginga, with whose name the cathedral will be inseparably connected, or the warlike Henry de Spencer, who drove from the city the adherents of Wat Tyler after they had inflicted great damage upon it under the leadership of John the Dyer, the see of Norwich was held by Bishop Bateman, the founder or Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and by others of no means importance in the times prior to the Reformation.

Subsequently to this period Joseph Hall, the contemporary of Shakspeare, and worthy to be mentioned among the best names of tho Elizabethan era, that one name only being excepted—excepto excipiendo— occupied the see. He has been called, for his prose compositions, the English Seneca, though he might with pernaps better reason be compared with Theophrastus, for his keen perception of the salient points of various characters and his intimate knowledge of human nature. His “Meditations” are one of the English classics, whilst his “Satires” display a marvellous vein of observant humour. His description of the dandy, with “so little in his purse, so much upon his back,” dining with Duke Humphrey in St. Paul’s, must often have risen before him as be paced along the nave of his own cathedral, lord of all he surveyed. His quips and quirks are over, but his tomb remains, and, with those of many other celebrities, forms one of the things that every visitor to Norwich should see. . . .

Long has the city been famous for its worsted manufacture, which, introduced by the Flemings in the time of Edward III., was afterwards improved by the Dutch, many of whom took refuge here from the cruelties of the infamous Duke of Alva—a monster in comparison with whom Nero and Commodus were humane men and Theodore an angel of mercy. One passage from Motley’s “Rise of the Dutch Republic” will explain why it was that the unhappy Netherlanders came over to Norwich or any other place that would give them a foothold:—“ Men were tortured, beheaded, hanged by the neck, and by the legs, burned before slow fires, pinched to death with red-hot tongs, broken upon the wheel, starved, and flayed alive.” Queen Elizabeth gave an asylum at Norwich to such as could escape from the tender mercies of this truculent hidalgo; and here they soon forgot their woes in the peaceful occupation of manufacturing druggets, crapes, and bombazine. The progress of trade and the improvement of machinery have long added to the coarser products of the loom many articles of world-wide repute, conspicuous among which are the Norwich shawls and crapes. Thus, among the cities of England, whether it be judged by its manufacturing industry, in which so large a population is almost wholly engaged; or by its love of the refinements that form a pleasant change from the monotony of labour, as shown in its renowned musical festivals; or, lastly, by its possession of historic traditions and remains of rare architectural grandeur, the British Association of Science have this year made no bad choice in fixing their head-quarters at the goodly city of Norwich. [170]

Bibliography

"Leaves from a Sketchbook: Norwich." Illustrated London News 53 (1868): 169-70. Hathi Trust online version of a copy in the Princeton University Library. Web. 25 May 2021.

Last modified 27 May 2021