s much as Victorian scientists adored their

tabletop experiments, they

were also keen to develop larger and more ambitious projects that

took great swathes of the globe as their laboratories. Over the course of the

nineteenth century, observers in far-flung

networks were trained on increasingly sensitive and

sophisticated instruments to collect, collated, and mathematically

process observations from which could be inferred — reliably and for the

first time — laws about global events, particularly in geophysics and

meteorology. The “British magnetic scheme,” as it was known at the time,

was part of this expansion. Unfolding over decades, the project aimed to

observe, record, and ultimately theorize about geomagnetic variations

that had long been familiar, particularly to navigators, but poorly

understood.

s much as Victorian scientists adored their

tabletop experiments, they

were also keen to develop larger and more ambitious projects that

took great swathes of the globe as their laboratories. Over the course of the

nineteenth century, observers in far-flung

networks were trained on increasingly sensitive and

sophisticated instruments to collect, collated, and mathematically

process observations from which could be inferred — reliably and for the

first time — laws about global events, particularly in geophysics and

meteorology. The “British magnetic scheme,” as it was known at the time,

was part of this expansion. Unfolding over decades, the project aimed to

observe, record, and ultimately theorize about geomagnetic variations

that had long been familiar, particularly to navigators, but poorly

understood.

The work had obvious practical utility: compass readings, always to some extent unreliable, became even more so on new iron ships; a better understanding of geomagnetic phenomena could certainly help here. But there were also less overtly practical reasons to support the project. Perhaps the most powerfully persuasive for early Victorians was recapturing lost national glory. In the late seventeenth century, the astronomer Edmund Halley (1656-1742)] made the first government-sponsored expeditions for the purpose of measuring magnetic variation. His work was overshadowed by advances made by eighteenth-century French scientists such as Pierre Charles Le Monnier (1715-1799), and Jean-Charles de Borda (1733-1799). Historian Jessica Ratcliff has usefully compared the geomagnetic scheme with another global Victorian scientific undertaking, the Transit of Venus project of the 1870s and 1880s, finding that in both cases, the leading lights of the Victorian scientific establishment were at least partly motivated to recapture Halley's dominant position (23). The work had an additional charm, as it involved only modest observational practices that nevertheless, despite their modesty, promised massive advancement in the theoretical understanding of the most basic natural laws. As William Vernon Harcourt, general secretary of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), breathlessly explained to its members in 1839, the enterprise promised to yield "a theory based on a legitimate representation of known facts" as well as "the true cause of the phenomena — and therein a completion of what Newton began — a revelation of new cosmical laws — a discovery of the nature and connexion of imponderable forces —all these possible results of approaching the heights of theory on what may prove to be their most accessible and measurable side" (qtd. in Cawood, p. 493). Harcourts’s excitement was infectious; the Victorian scientific establishment was quickly infected with what historians such as Christopher Carter have dubbed "magnetic fever.”

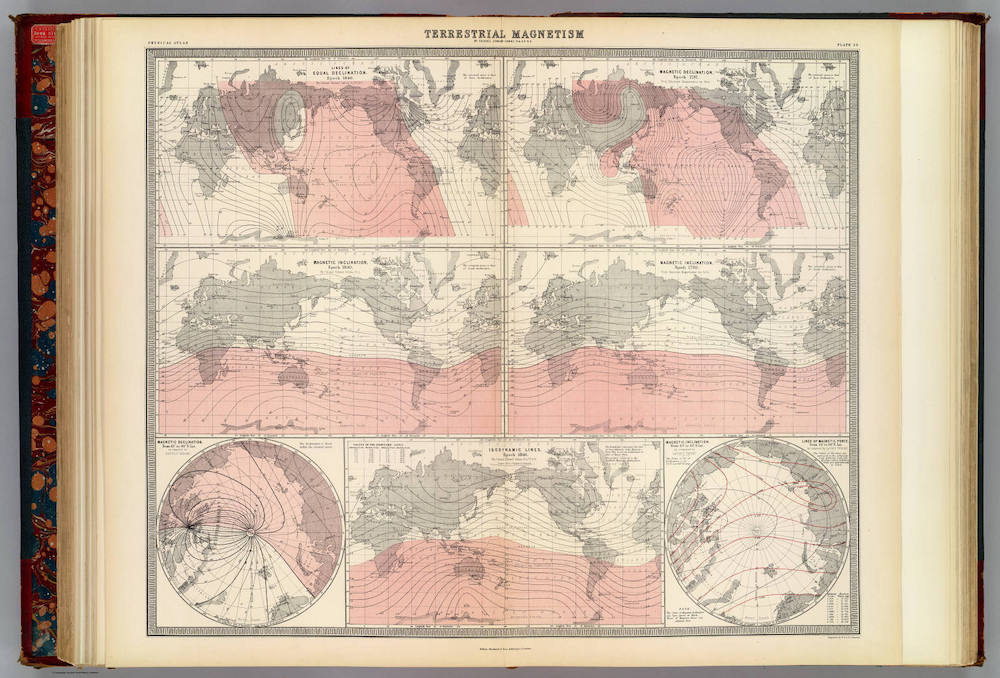

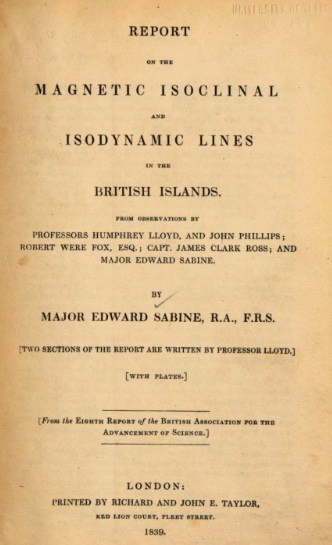

Left to right: (a) Portrait of Edward Sabine by Stephen Pearce, oil on millboard, 1850. Reproduced by courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery. (b) Set of isocline maps of various geomagnetic phenomena created by Sabine and published in The physical atlas of natural phenomena by Alexander Keith Johnston (1856). Internet Archive. (c) Title page of Sabine's Report on the Magnetic Isoclinal and Isodynamic Lines of the British Islands (1839), with two contributions by Humphry Lloyd. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In addition to the Admiralty, three other organizations became deeply involved in the geomagnetic project. Of them, the BAAS was the most important. The organization’s encouragement of geomagnetic research was not an isolated or one-off enthusiasm but, as historian Jonathan Cawood puts it, “part of a wider conception of the nature and conduct of science” espoused and promoted by the organization’s “most powerful” members (Cawood 500; see also Carter 43-54). As early as 1831, the Committee of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), urged measurements of magnetic inclination (“dip”) and intensity at points all over England, Scotland and Ireland; by their 1832 annual meeting at Oxford, the BAAS was calling for an international magnetic venture on par with the growing network of Continental observatories organized by Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) and mathematician and astronomer Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855) at Goettingen (Cawood 500; Goodman 2016, 252-53).

Over the next decade interest in geomagnetic phenomena not only intensified but also broadened to include much of the globe, as British scientists lobbied for and successfully obtained funding for expeditions to measure geomagnetic phenomena and to build geomagnetic observational outposts in the colonies. Two of the most influential Victorian scientists, the astronomer John F.W. Herschel (1792-1871) and the natural philosopher William Whewell (1794-1866), joined forces with Sabine to lobby for a global system for measuring geomagnetic phenomena. The proposed investigation included a voyage to the Antarctic and the creation of a network of magnetic observatories to measure magnetic variation at far-flung points around the planet. Again, the project had a scientifically simple premise: the idea was to derive the laws governing observed changes in the earth’s magnetic field from the largest possible set of observations taken worldwide. By 1835, cooperative agreements with Académie des Sciences in Paris and the East India Company substantially broadened the scope of the project as proposed in 1831, though the practical objectives remained largely the same: to mount a southern expedition and to establish a set of fixed observatories in England and the colonies (Cawood 501).

Humphry Lloyd (1802-1881), provost and professor of natural philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin, also played a vital early role. Since 1833, and after a period of difficulty obtaining the necessary instruments, Lloyd had been engaged in a magnetic survey of Ireland. When Sabine was posted to Limerick, around 1833, he and Lloyd joined forces (Goodman 2016, 253). Introducing the project in the first pages of his initial 1839 report, Sabine recalled:

The Magnetic Survey of the British Islands originated with a few persons interested in that branch of experimental science who attended the third Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held at Cambridge in June 1833. On his return to Dublin from attendance at that Meeting, Dr. Humphry Lloyd [...] proposed to myself, then serving on the Staff of the Army in Ireland, to unite with him in an endeavour to realize such an undertaking. (265)

Sabine and Lloyd's network of magnetic observers eventually expanded to include the naval officer and polar explorer James Clark Ross (1800-1862) as well as geologists John Phillips (1800-1874), who was then working with Henry de la Beche (1796-1855) on the Ordnance Geological Survey of Britain, and Robert Were Fox (1798-1877), whose special talent for instrument design additionally enhanced the project.

In addition to spurring this important work, Lloyd’s involvement brought Sabine into to closer contact with the Royal Society which, in turn, provided additional support. In 1838, Lloyd urged the Royal Society to coordinate with Sabine in funding the Antarctic expedition as well as the construction of fixed observatories in the colonies. From this point, the Royal Society also worked closely with the BAAS in presenting proposals for magnetic research to the government.

Herschel’s involvement only deepened over the course of the succeeding decade. In 1828, recently returned to London after four years of intensive work on the Cape, where he had undertaken a variety of astronomical and educational projects, Herschel began to press the Meteorological Committee of the Royal Society to support the combined study of weather and geomagnetism in specialized observatories (Cawood 502, 507) Lloyd and Sabine approached him soon after, with good results. Herschel then contacted Gauss at Goettingen, and there followed a lively correspondence on the practical and theoretical aspects of the British project. In particular Gauss offered detailed information about instrumentation and observational practices (Josefowicz 2005). Once Herschel was involved, support for the project began to snowball, and even commercial enterprises answered the call. By April 1838, a set of magnetic instruments was on its way to Tasmania, and Herschel directed Lloyd to prepare similar orders, as well as instructions for observers and forms for recording and reducing their measurements, for the other observatories in Canada, the Cape of Good Hope, and St. Helena (Carter 54-64).

The path of the geomagnetic project was not always smooth. Through the spring of 1839, the project was beset by problems, delays, and doubts about the practicalities of supplying instruments and trained observers to the fixed observatories. Because these stumbling blocks threatened to undermine efforts to get the Antarctic expedition, led by Ross, underway, Sabine was inclined to separate the two initiatives. Lloyd however preferred to keep them linked. As he wrote to Sabine in late 1838: “I cannot bring myself to accede to your notion of separating the two parts of this grand project” (qtd. in Carter 56, note 82). Working closely with Herschel, Lloyd convinced the Royal Society that a merged program was preferable. Sabine soon came around, perhaps as a result of his feeling that the Royal Society’s imprimatur was too important to risk losing by objecting too vigorously to Lloyd (Carter 57-62).

The British East India Company was a third powerful influence over the course of the Magnetic Crusade. Under the leadership of Captain Thomas Jervis, who since early 1838 had been pressing the Company’s directors to support a survey with magnetic research in central Asia. Writing in August 1838 to James Melville, chief secretary at the East India Company, Jervis urged the disbursement of funds sufficient to cover the cost of outfitting three fixed observatories and and six additional traveling ones in the Raj; those bound for these observatories were specially trained by Lloyd in Dublin before being dispatched to their posts (Carter 65-66).

Funding for the geomagnetic scheme was renewed at three-year intervals, in 1842, 1845, and 1848. Each time the process was fraught (Carter 120-122). Mounting skepticism could be sensed in sneers about the project’s ambitions, as the perceived overreach led critics to dub it a “Magnetic Crusade.” Even Herschel grew frustrated with Sabine’s desire to take ever more measurements and make ever more charts — activities he derided, drolly, as compulsive “chartism.” In 1845, when the project was renewed for its last three-year term, Herschel finally withdrew from the project, perhaps sensing that Britain's “magnetic fever” had finally run its course.

Links to Related Material

- The Victorians and the Earth's Magnetic Field

- Studying the Earth's Magnetic Field in India

- Dr. Henry Acland at the Toronto Observatory

- The Genius of Electricity Uniting Parts of the Earth (frieze) by Walter Crane

Bibliography

Carter, Christopher. Magnetic Fever: Global Imperialism and Empiricism in the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2009.

Cawood, John. “The Magnetic Crusade: Science and Politics in Early Victorian Britain.” Isis 70 (1979): 493-518.

Goodman, Matthew. “Proving Instruments Credible in the Early Nineteenth Century: The British Magnetic Survey and Site-Specific Instrumentation.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society 70 (2016): 251-268.

Ratcliff, Jessica. The Transit of Venus Enterprise in Victorian Britain. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016.

Last modified 8 September 2023